The man within the poetry

A giant of the Australian page, Les Murray wrote poems about his home, his beloved wife, his fears.

Les Murray wrote poems about his mother, his father, his home, his beloved wife and children, his fears and his failings. He was too humble to write about his humility, that casual way he’d shrug off a comment about his genius with his trademark, “Hmmmmfff”, his regular and wise neither-here-nor-there grunt assessment of another human opinion.

“Among the three or four leading English-language poets,” fawned The New Yorker.

“Hmmmmfff.”

“Les Murray in line for Nobel prize for literature!”

“Hmmmmfff.”

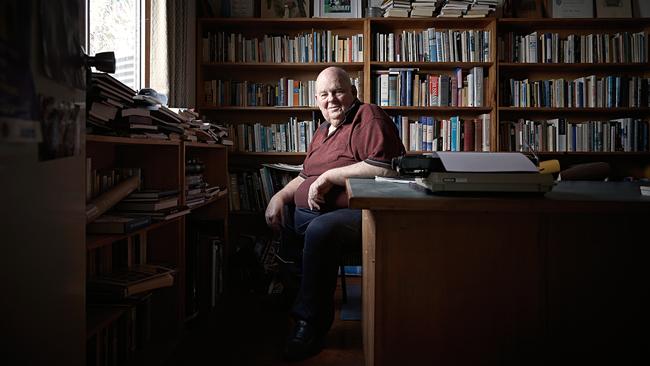

He wasn’t one for awards, he wasn’t big on plaudits. He would never waste space on a shelf for a trophy if a book could take its place. In his beloved and rambling house in Bunyah, mid-north coast NSW, he allowed himself only one indulgence of pride that pointed to his mighty literary career. It was a framed A4-sized flyer that hung on his living room wall that house guests might glimpse on their way to the dunny. A modest shopfront ad for “poetry readings every second Sunday” at Valona Deli, 1323 Pomona St, Crockett, California. A cheap and poorly illustrated flyer from a decade ago, the only clue to his staggering output — six decades of “scribbling” about himself, his family, his bushland, his beloved country, his glorious God.

“Featuring Les Murray! Australia’s leading poet and one of the greatest contemporary poets writing in English. His work has been published in 10 languages. Les Murray has won many literary awards including the Grace Leven Prize (1980, 1990) and the prestigious TS Eliot Award. His 1998 verse novel, Fredy Neptune, was hailed in Britain and America as a masterpiece of 20th century literature and awarded the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry on the recommendation of Ted Hughes.”

His signature writing method, Five and One, always served him well. “Five fingers that write, and one that can type,” he said. He scribbled his grand and original thoughts in a notepad first, crafted lines of devastating truth about love and loss and living and “learning human”, watching his complex species from the view of the eternal outsider, Australia’s truest correspondent on the human condition who never seemed to sit comfortably among humankind. Then he’d take his scribbles into his office, adorned with endless books and a defiant note to self that simply said, “NO!”, and laboriously single-finger-tap a masterpiece on to an old school typewriter, and rewrite it five, 10, 15 times until the work achieved what, nine times out of 10, he gave us: illumination.

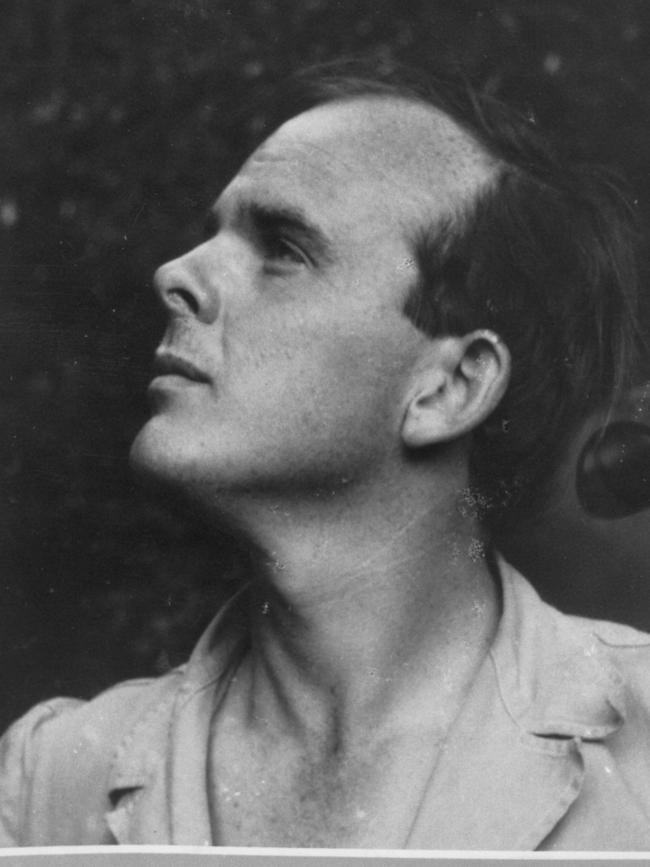

Leslie Allan Murray was born in 1938 in Nabiac, a village only a short drive from the Bunyah family home where he would spend much of his adult life. The first poem he ever wrote was penned on Christmas afternoon, 1956. Complete rubbish, he said, but touching on themes he explored for six decades: home, himself, his mum and dad, Bunyah, where he belonged. “Well, it all had to be solved,” he said.

He always had a faint scar beneath his left nostril — his earliest memory, falling off the veranda of his boyhood shack, the long-vanished slab house that once stood not too far away from the Bunyah Dance Hall, where a penniless dairy farmer’s only child taught himself to read at the age of nine, taught himself to grieve at the age of 13.

No weight would he let my mother carry.

Instead, she wielded handles in the kitchen and dairy, singing often, gave saucepan-boiled injections with her ward-sister skill, nursed neighbours, scorned gossips, ran committees.

She gave me her factual tone, her facial bones, her will, not her beautiful voice

But her straightness and her clarity.

I did not know back then nor for many years what it was, after me, she could not carry.

That poem, Weights, was for his mother, Miriam, who died in 1951. “They had three more children but they died in the womb,” Les told The Australian in 2014. “The last one killed my mother. It’s about that business of mine, thinking that I caused her miscarriages. She was in a state of clinical depression for the last six years of the 12 I knew her. I think she suspected my birth caused her troubles. It’s a real bugger to feel that your birth might have prevented theirs.

“You can become an only child by taking away their lullaby.”

That was a stunning last line and, like most of his profound wisdoms, straight off the cuff.

“Like a lot of good lines, it’s hard bought,” he said.

The other defining event of his life occurred before he was born, a tragic story of how his grandfather, Allan, a heavy-burdened spirit drinker, long blamed Les’s father, Cecil, for the death of Cecil’s brother, Archie. Cecil, a knowledgeable bushman, had refused to chop down a farm tree at the request of his pressuring father, suspecting, correctly, that it was rotten inside and dangerously positioned for the chop. Les’s grandfather, instead, pressured the less-experienced Archie to chop the tree that snapped off at the top and killed him. After his beloved wife’s death, Cecil, Les said, came to believe that all that he touched was “accursed”.

Dark and rich matters the poet would process across his writing life, channelling generational pains into immortal epics such as 1963’s The Widower in the Country.

I’ll get up soon, and leave my bed unmade

I’ll go outside and split off kindling wood from the yellow-box log that lies beside the gate, and the sun will be high, for I get up late now

His biographer, Peter Alexander, described his poems as “remarkable for their diversity and range, but a number of themes run through them from start to finish”.

“Chief among these are his celebration of life and nature in all their diversity,” Alexander said. “His sense of the sanctity of human existence, and yet of its pathos as well; his association with ‘the people’, particularly common country folk, and a concomitant distrust of elites; and his strong sense of what it means to be an Australian, paradoxically combined with a deep-rooted cosmopolitanism resulting from his wide reading in a range of languages.

“His poetry is remarkable for its energy and for the bounding Elizabethan fecundity of its images. In the manner of the 17th-century poets too, it is often intellectually demanding, while never surrendering its claim to be popular. Its emotional range is very wide: Murray is a master of lightly humorous verse and of brilliant description, but he can also be deeply moving or bitingly satirical.”

“I am my poems,” Murray said. “That’s where you’ll find me.”

There he is in hilarious wonders such as The Dream of Wearing Shorts Forever; The Quality of Sprawl, Black Belt in Martial Arts. There he is in Sex is a Nazi, writing about the cruel girls of Taree High School who bullied the awkward teenaged Les.

“It was a howling bitch of a place full of bullies who enjoyed tormenting,” he said. “They realised quickly I had no common sense and no defenders. All girls, and you can’t punch girls. It really left a deep mark.”

There he is standing near Martin Place watching a stranger weep in his hugely popular classic, An Absolutely Ordinary Rainbow.

The man we surround, the man no one approaches

simply weeps, and does not cover it, weeps

not like a child, not like the wind, like a man

and does not declaim it, nor beat his breast, nor even

sob very loudly — yet the dignity of his weeping

holds us back from his space, the hollow he makes about him

in the midday light, in his pentagram of sorrow,

and uniforms back in the crowd who tried to seize him

stare out at him, and feel, with amazement, their minds

longing for tears as children for a rainbow.

He found his place at the University of Sydney and in Sydney itself, where he didn’t just read books, he read entire libraries. “I wish a new book would come out,” he once said. “I think I’ve read them all.” He gradually filled his mind with 1,025,000 or more English language words and began using them to slice and savage and sort out the world around him, with able assistance from those bold members of the Sydney “Push”: Clive James, Germaine Greer, Robert Hughes and his dear old Bondi flatmate, Bob Ellis.

His work ethic was staggering. His contribution to literary criticism alone would be legacy enough, without even mentioning his relentless stream of relentlessly brilliant volumes of poetry: The Weatherboard Cathedral (1969), Poems Against Economics (1972), Selected Poems: The Vernacular Republic (1976), Ethnic Radio (1977), The Boys Who Stole the Funeral (1980), Equanimities (1982), The Vernacular Republic: Poems 1961-1981 (1982), The People’s Otherworld (1983), The Daylight Moon (1987), The Idyll Wheel (1989), Dog Fox Field (1990), Translations from the Natural World (1992), Subhuman Redneck Poems (1996), Fredy Neptune (1998), Conscious & Verbal (2000), and on and on it goes. He never stopped thinking so he never stopped writing.

The world was always waiting for him outside of Bunyah and he ate it up, quickly and unceremoniously. He ate life up, every morsel of it, the way he ate up the meat and gravy meals of his beloved wife, Valerie, his great leveller, his great inspiration, his world beyond words.

It was Valerie who saved him from what he dubbed “The Big Sick”, the period of roughly seven years from about 1988 that he battled depression, a period that coincided with a crippling intestinal abscess that led to liver surgery that led to a near-death three-week coma in 1996. “Don’t you bloody die on me, I’m not finished with you yet!” Valerie said beside his hospital bed.

Few have written as eloquently about depression as Murray wrote in his bloodletting 1997 book, Killing the Black Dog. “I had a bad year and a half of it and it largely went away and it just became latent,” he said. “And then it came back. It said, ‘My name is Depression and I’m here to give you a badddddddd time’. I never killed the black dog. You can’t. Nobody ever kills the black dog.”

Valerie saved him. His five children — Christina, Daniel, Clare, Alexander and Peter — saved him. The words saved him. He wrote furiously through his troubles, wrote about animals and plants and things that didn’t have to breathe to exist. “I was crazy as a loon,” he said. “It was a great relief to go off into the soul of a kangaroo or a bear for a while. It was a relief from being me.”

(Echidna)

Crumpled in a coign I was milk-tufted with my suckling

till he prickled.

He entered the earth pouch then

and learned ant-ribbon,

the gloss we put like lightning on the brimming ones.

Life is fat is sleep. I feast life on and sleep it,

deep loveself in calm.

I awaken to spikes of food-sheathing, of mulling fertile egg,

of sun, of formic gravels,

of worms, dab hunting, of fanning under quill-ruff when budged:

all are rinds, to sleep.

Corner-footed tongue-scabbard, I am trundling doze

and wherever I put it

is exactly right. Sleep goes there.

He could write about a busy echidna and make you weep. He could write about weeping and make you laugh. He could write about disbelieving and make you believe. He could write about dreaming and make you wake up to yourself. He could write.

(The Meaning of Existence)

Everything except language

knows the meaning of existence.

Trees, planets, rivers, time

know nothing else. They express it

moment by moment as the universe.

Even this fool of a body

lives it in part, and would

have full dignity within it

but for the ignorant freedom

of my talking mind.

“I am my poems,” he said. “That’s where you’ll find me.”

And he was right. That’s where he is. That’s where he’ll always be.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout