World of cinema floats into 72nd Venice film festival

Australia was particularly well represented at Venice this year with three features.

Both the golden and silver lions at the 72nd Venice film festival were won by films from Latin America. The top prize went to the Venezuelan drama From Afar, directed by Lorenzo Vigas, an intense story of a middle-aged loner (Alfredo Castro) who befriends a young street kid (Luis Silva), a relationship that leads to tragedy.

The second prize was awarded to an Argentinian film, The Clan, by director Pablo Trapero, which is based on real events. A former security agent during the dictatorship of the 1970s, who loses his position with the coming of democracy in the early 80s, continues to kidnap innocent people, this time seeking ransom for their return (though he makes sure the victims are never seen again). As the psychopathic man who involves his entire family in his crimes, Guillermo Francella is chillingly good.

The most original film of the festival’s main competition was Anomalisa, an animated puppet film co-directed by Charlie Kaufman (who scripted) and Duke Johnson, which won the grand prize of the jury (third prize). Essentially it’s a film about a midlife crisis: a British-born author of self-help books (voiced by David Thewlis) spends one night in Cincinatti where he is to make a speech. Everyone he contacts, men, women and children, sound alike — and no wonder, because they’re all voiced by Tom Noonan. All, that is, until he meets Lisa (Jennifer Jason Leigh), and she seems likely to change his life.

Deftly scripted, filled with Kaufman’s trademark humour, but also profound and pretty moving, this is a film of considerable distinction.

The acting awards went to Fabrice Luchini for his role as a judge who falls in love with a juror in L’hermine, a pleasant but unremarkable French comedy, and to Valeria Golino for her role as a woman involved with an egotistical actor in For Your Love, the weakest of the four Italian films in the competition. A special prize went to the Turkish film Frenzy, by Emin Alper, which is set in the poorest suburbs of Istanbul. A convict is given early parole on condition he works for state security spying on the locals — including his brother — some of whom are suspected of plotting acts of terrorism. It’s a creepy, mysterious, disturbing experience.

Australia was particularly well represented at Venice this year with three features plus a co-production with Canada in official sections. For 17-year-old actress Odessa Young, who plays the title roles in two of the films, Looking for Grace and The Daughter, this has been quite a triumph.

Sue Brooks’s Looking for Grace is an ambitious film in which the title character steals money from her parents (Richard Roxburgh, Radha Mitchell) and heads off by bus from her home in Western Australia with a friend to attend a rock concert — but never gets there. The narrative is told from different perspectives, and Brooks switches moods between suspense and a stylised humour that doesn’t always work. Still, the performances of Young, and Terry Norris, who plays an ageing private investigator, are utterly delightful.

Simon Stone’s The Daughter, which already has screened successfully at Australian festivals, was selected as the closing film in the Venice Days section of the festival. Stone originally directed this updating of Ibsen’s The Wild Duck for the stage and has turned the material into a completely cinematic experience, filming around Tumut in NSW, with Young as Hedwig, the “wild duck” of the title, and there’s an outstanding supporting cast that includes Ewen Leslie and Miranda Otto as her parents, Sam Neill as her grandfather, Geoffrey Rush as a wealthy businessman whose timber mill provides employment for the town and Paul Schneider as Henry’s son, who has lived for many years in America.

All the performances are outstanding, and Stone makes a giant leap from stage to screen with this flawless adaptation.

Tanna, which won the audience award for best film in the Critics Week section of the festival, is the feature film debut for Australian documentarists Bentley Dean and Martin Butler, who filmed on the island that gives the film its title and that is located at the south of the Vanuatu archipelago. The film tells a simple story of a young couple caught up in rivalry between two opposing tribes that still live traditionally in this lush environment. The actors had never seen a film before, let alone performed before the camera, and they give wonderfully naturalistic performances, especially young Marceline Rofit, who plays the little sister of the lovesick heroine. An active volcano becomes almost another actor in this attractive and original drama.

Australian Michael Rowe made an impression in 2010 with Leap Year, which he made in Mexico and which was awarded the best first feature of the Cannes festival; his latest, Early Winter, which won the award for best film in the Venice Days section of the festival, is set in Quebec and is an intense examination of the intimate lives of a married couple with two sons, a relationship undermined by the husband’s jealousy. Beautifully composed images illustrate a story that unfolds not so much with major incidents but with small accumulating details. Paul Doucet and Suzanne Clement give impressive performances as the ordinary couple in crisis.

In Laurie Anderson’s Heart of a Dog, the visual artist and singer narrates a personal reminiscence about her life, especially her relationship with a beloved dog. While hard to classify, this combination of old 8mm movies, drawings and home video stays in the memory long after it has ended.

Cary Fukunaga’s Beasts of No Nation seems likely to go down in film history as the first feature film produced by Netflix, but on any level it’s an impressive, often harrowing, exploration of the plight of child soldiers involved against their will in a violent African conflict. Young Abraham Attah gives a heartbreaking performance as a kid who, after the murder of all members of his family, is forced to become a soldier in the army of a charismatic leader — the superb Idris Elba.

Two films screened out of competition told true-life crime sagas set in the city of Boston. Stuart Cooper’s Black Mass stars Johnny Depp, under heavy makeup, as James “Whitey” Bulger, a ruthless criminal, and Joel Edgerton — outstanding — as an FBI agent who protects him mainly because, as children, they had grown up together in Irish Catholic South Boston. This is one of the best thrillers of its type since the last Martin Scorsese gangster movie.

Less violent but perhaps even more disturbing is Tom McCarthy’s Spotlight, which charts the campaign of a newspaper, The Boston Globe, to expose scandals involving the abuse of children by Catholic priests.

Neither of these films paints the church in a positive light, but McCarthy’s film — which stars Michael Keaton and Mark Ruffalo as newspapermen — is, though less eventful, the more disturbing of the two.

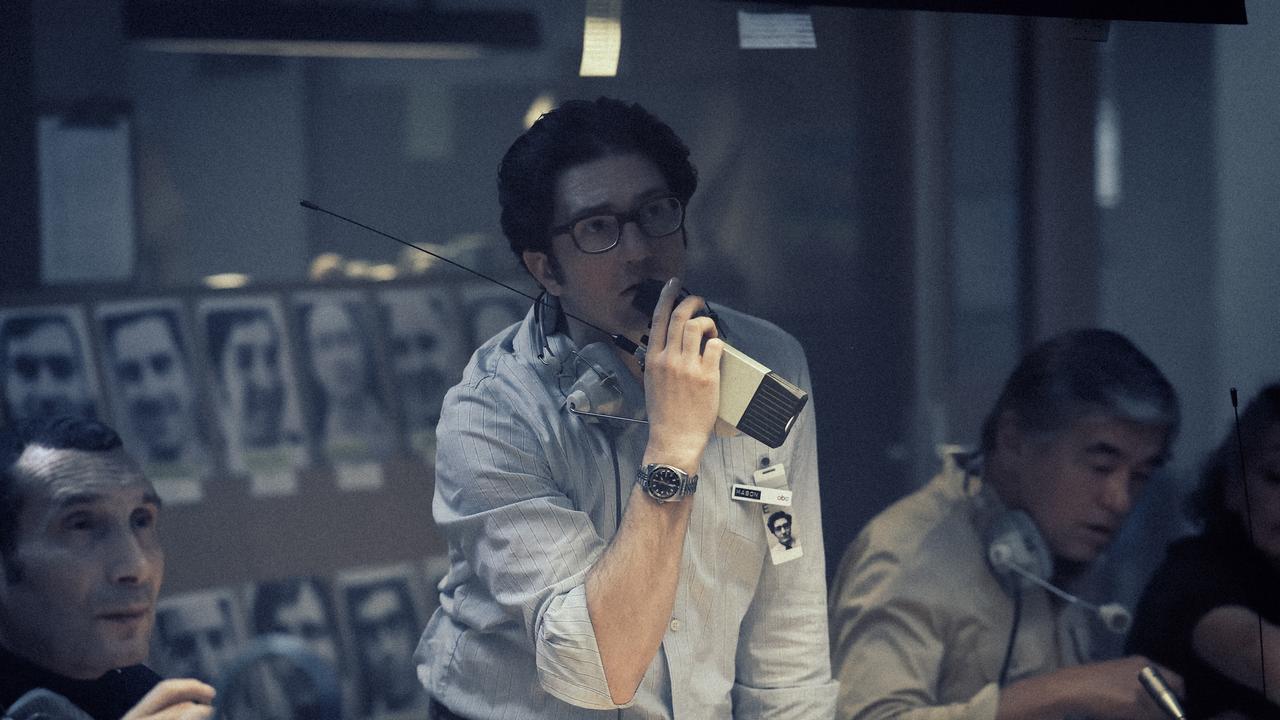

Another kind of crime — political assassination — is the subject of Israeli director Amos Gitai’s Rabin: The Last Day, which illustrates the aftermath of the 1995 murder of Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin by a right-wing fanatic, uses interviews and re-creations of testimony given to an inquiry as well as a re-enacted encounter with the killer himself. All the texts are genuine, and the accumulated evidence assembled in this long, dry but compelling film, points to the responsibility of some political leaders, including the present Prime Minister, who took part in inflammatory anti-Rabin speeches in the days before the killing.

A different kind of true story unfolds in The Danish Girl, the latest prestige production from Tom Hooper, director of The King’s Speech. Eddie Redmayne follows his Oscar-winning portrayal of Stephen Hawking with a nuanced portrayal of Einar Wegener, a Danish landscape artist, who became Lili Elbe in a pioneering example of transgender sexuality. As the loyal wife of the conflicted protagonist, Alicia Vikander gives another memorable performance.

Alexander Sokurov’s Francofonia is a song of praise to the Louvre museum (in fact, to all museums and galleries) and explores how the Louvre survived the German occupation during World War II. Sokurov, who previously celebrated the Hermitage in Russian Ark, is an original filmmaker, and this is one of his finest achievements.

The Italian films weren’t particularly distinguished this year, and the best French film, Taj Mahal, was in the Horizons section of the festival, not the main competition. It’s a chilling depiction of an English teenager trapped in the hotel of that name in Mumbai during the 2008 terrorist attack on the establishment. Director Nicolas Saada creates a palpable feeling of claustrophobia as the terrified girl locks herself in the room, not knowing what’s going on outside.

For sheer cinematic smarts, veteran director Jerzy Skolimowski’s Polish entry, 11 Minutes, would be hard to beat. The film introduces several characters involved in a variety of activities in the centre of Warsaw before a terrible accident occurs — a film filled with intriguing characters and all of it staged with consummate skill.

For much of its length Behemoth, by Zhao Liang, a documentary about work at a vast open-cut coalmine, seems conventional, though extremely well photographed. The kicker comes near the end, when we meet miners whose health has been ruined by their work and see the empty ghost cities that are springing up in China as a result of all this feverish activity.

Though definitely too long, the film is ultimately a stark reminder of the price paid by reckless overdevelopment.