There’s cultural value in projecting Australia on screen

Australians respond warmly to ‘Australianness’ on screen, but local authenticity isn’t a requirement of industry or funding bodies.

Nobody with Australian film and television drama in mind is enthusiastically shouting “What do we want? Cultural value! When do we want it? NOW!” Especially not publicly. Not the people who pay for it, make it or put it on screen.

Remember being told as a child to eat your vegetables because they’re good for you? The term “cultural value” has that tone about it. It’s old-fashioned, uncool. For some, it is marketing suicide to tout a show’s Australian credentials to Australian viewers. State and federal governments, which underpin production with taxpayer funding and regulation, aren’t making much noise about cultural value either.

It is referred to only when strictly necessary. No one ever interrogates how it is best created and by whom. There’s a whiff of jingoism about it, perhaps – which is seen as not good for a production industry that prides itself on being global.

Measuring the Cultural Value of Australia’s Screen Sector, a report that appeared in 2016, was commissioned by Screen Australia to get a “credible, comprehensive assessment” of the cultural value of, predominantly, Australian scripted fiction, the modern term for drama.

For the report, 928 Australians were asked to identify the three most culturally impactful pieces of Australian content. The heavy hitters of the 271 productions mentioned were Crocodile Dundee, Home and Away, Neighbours, The Castle, Mad Max, Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, Four Corners, Australia, Gallipoli, Q&A and Rabbit-Proof Fence.

Diverse though the list is, the “Australianness” of each drama is as clear as day. Cinema owners often say that when an Australian film manages to tap into the zeitgeist, it goes off at the box office. Word of mouth can explode around a homegrown series.

The intensity of feeling that drives this momentum is because Australia is up on screen in look and feel. The response might be amusement, joy, or horror. Some viewers will respond to stupidity, others to seriousness. A damn good belly laugh is as good as a lump in the throat. The intensity comes from a sense of recognition and belonging.

Without recognisable on-screen Australianness, or an Australian look and feel, value of the kind I am talking about is unobtainable. Australianness doesn’t guarantee local cultural value because the drama has to deliver, and different things appeal to different people. But it delivers the potential for it.

Australianness might reflect a sense of place. If creatures as peculiar as kangaroos are in our lives, why not flaunt them (though be prepared for some eye-rolling). It is likely, however, to be related to Australian characters because human connection is a powerful thing. Those Australian characters might be leading ordinary lives, as in Home and Away, or having fun hunting vampires, as in the eight-part series Firebite. This unmistakably Australian show for US streaming service AMC+ has Australia baked into every frame via its characters and the gorgeousness of the desert at sunrise and sunset.

There are so many things that recognisable on-screen Australianness can be, but it has an underlying unity of soul. One size does not fit all. Ideally, there is enough homegrown drama to cater for every taste.

Most Australian drama is about Australians and set in Australia, but not all of it is. What is never discussed is how Australian drama, as defined by industry and government, doesn’t have to have an Australian look and feel.

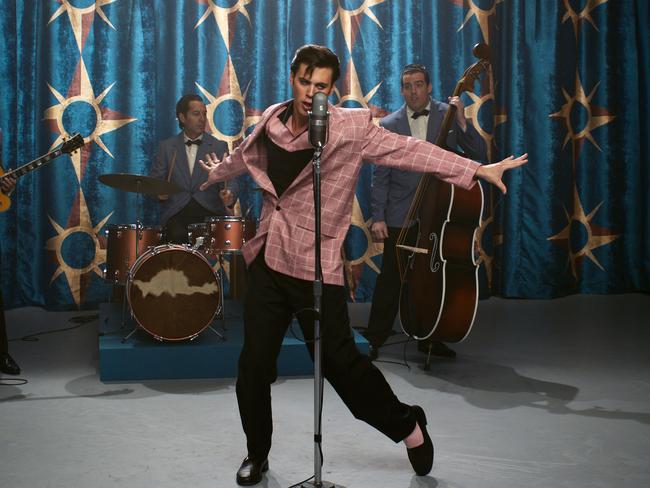

Director Baz Luhrmann’s sensational debut Strictly Ballroom and his still divisive Australia radiate on-screen Australianness. But most of his films do not: think Moulin Rouge!, Romeo + Juliet, The Great Gatsby and the newly released Elvis. All except Romeo + Juliet were filmed in Australia with a long roll call of Australians on and off screen and buckets of international investment.

Three of the top 10 Australian films in cinemas last year – the two animations Peter Rabbit 2 (in the number one spot) and Maya the Bee: The Golden Orb, and the action fantasy Mortal Kombat – had no on-screen Australianness.

The other seven did: The Dry, Penguin Bloom, High Ground, June Again, Buckley’s Chance, Long Story Short and the documentary Girls Can’t Surf.

Golden Orb is a co-production, made under a formal arrangement between the Australian and German governments. The much heralded The Power of the Dog is a co- production with New Zealand. Official co-productions are eligible for local funds in the partner countries. Many don’t have any Australianness. This is meant to even out across the co-production slate, but it’s not something that’s discussed publicly.

Australian drama production is underpinned by Australian taxpayer money. To access any of this funding, all projects except co-productions must pass a significant Australian content test.

Subject matter; the place where a film is to be made; the nationalities and places of residence of the people undertaking production; where production expenditure flows; and other criteria deemed relevant are taken into consideration. Precedents indicate that if the creators are Australian and the production company is Australian, they are probably making something that will be judged to be Australian regardless of what is happening on screen. That’s because of a firm belief that filmmakers should be free to make anything, anywhere, with anyone.

Agreed.

The eight-part Australian series Clickbait, a dark, fast-moving tale of kidnap, revenge and internet trickery, was shot in Australia, set in Oakland in the US, and had hardly a skerrick of Australia on screen. Upon release, it hit the number one spot on Netflix in more than 20 countries.

This level of success from Australian creatives is exciting to see, as is their success at accessing an eye-popping $52m from Netflix. People who think it’s straightforward to compete against the best in the world given Australia’s minimal development and production budgets need to take off their rose-coloured glasses.

Some filmmakers purposefully water down Australianness. Anthony Hayes raised the budget for the dystopian Gold, his second feature as a director, on the strength of US actor Zac Efron. “There are so many people after content, but at the same time you need to be a little less parochial in some aspects, hence the American accents and multilingual signs,” Hayes said. Efron didn’t have to adopt an accent, but co-stars Hayes and Susie Porter did.

It’s safe to assume all these dramas received Australian government funding in some form or another. This paper is not arguing that they shouldn’t.

It is arguing that more regard needs to be paid to supporting dramas with Australianness because only it can generate local cultural value – which is the reason the Australian industry is subsidised in the first place.

Edited extract from Nobody Talks About Australianness on our Screens, by Sandy George, published by the New Platform Papers. Download free at currencyhouse.org.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout