The Wolfpack: how six New York boys grew up together, in isolation

New York boys raised together, but in isolation.

Filmmaker Crystal Moselle says she is already looking for her next project after the extraordinary tale she tells in The Wolfpack.

“I’m wandering the streets of Australia, hoping,” the American says with a laugh.

That is how she stumbled on the subject of her film, the six Angulo brothers, who had been locked and isolated by their father in their New York apartment.

Chronicling their lives, and the subsequent success of the film, has been “a wild experience”, she admits, right from the moment she “followed them down the street”.

Five years ago the six brothers, then aged 11 to 18, ran past her in New York’s East Village, a vision of pony-tailed beauty. Moselle was intrigued because she had not seen them before in her close-knit neighbourhood. “It was such a surreal experience,” she says. “In my head it was in slow motion. I ran after them and asked them where they were from.”

They said they were from Delancey Street but they had been warned not to talk to strangers. Nevertheless, they asked Moselle what she did and they instantly warmed to her when she told them she was a filmmaker.

“And when they said they were interested in getting into the business of filmmaking, I was like: ‘Cool, I have a skill I can teach some kids that seem to be cool.”

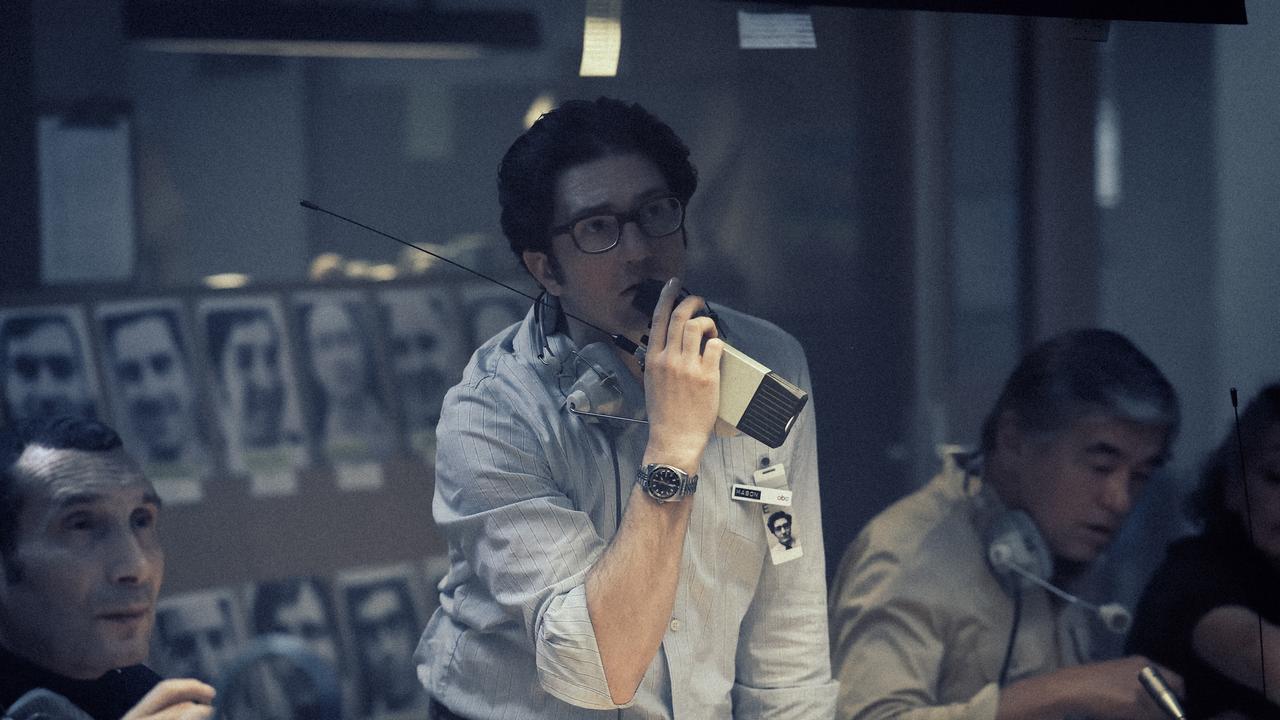

She befriended them during the following months, thrilled as they showed her their favourite hobby: writing out screenplays from their favourite movies and re-enacting scenes with an enthusiastic precision and invention. Reservoir Dogs was a particular favourite.

She thought they were cool.

“Oh yeah, are you kidding me?” she says. “I never felt like they were creepy at all. I thought they were endearing and so excited about life and determined. I just felt instantly akin to them.”

Their passion for film wasn’t their real story, though.

And it took Moselle some months to discover it.

They were film nuts because, in essence, that was how they experienced the world.

Their father, a Hare Krishna devotee, had not allowed them out of their 16th-floor public housing apartment fearing the crime, drugs and depravity they might encounter outside. The first-born girl, Visnu, and her six younger brothers were all given Sanskrit names — Bhagavan, Govinda, Narayana, Mukunda, Krsna and Jagadisa — and all of them remained indoors. It was all they knew other than the world as seen through movies and the occasional visit to a doctor or dentist at their mother’s insistence.

Shortly before they met Moselle, Mukunda had made a break for it, venturing outside in a mask modelled on the Michael Myers character in Halloween. Obviously, it did not end well, with police picking him up after complaints and sending him to a hospital for a mental evaluation after he was unresponsive to their questions and wouldn’t take the mask off.

“Their entire lives changed after that moment,” Moselle says. “He hadn’t been out of the house alone ever and then he was put in a mental institution for a week.”

The family passed a cursory check by the relevant authorities after Mukunda’s evaluation.

The kids were healthy and nothing seemed awry beyond more socialisation therapy needed for the three youngest.

Moselle helped that socialisation, initially unwittingly, as they began to venture out more.

“I think that, just from meeting them, I knew they were raised differently from your normal kids,” she says. “They were articulate and their point of view and questions about things were smart.

“Then it was just like this organic process of slowly figuring out what the story is.”

She met them in their first week “out”, although Moselle is unwilling to take any credit for their socialisation. After all, she says with a laugh, Makunda means “the giver of freedom”. “So they were already exercising that and maybe I was just there to help them along the way as a guide,” she says. “They went after what they really wanted to go after.”

Despite their seeming balance and sanity, she says they were not happy.

She is unwilling to address the issue of abuse, and the film tiptoes around it too, but she knows the brothers “wanted to be outside, to have normal friends, to experience life”.

The boys were open about showing their copious video footage about their insular lives though. Moselle had mixed emotions while watching them, seeing kids who were trapped yet entertaining themselves. “But it’s kind of like Instagram,” she adds. “People get to see the highlights of our life. With them, it was really like a search, looking between the lines and seeing what’s between it all.”

The two youngest brothers, who have changed their names to Glenn and Eddie (after rock stars Frey and Van Halen), haven’t seen the film but have consented to its release. Their father has seen it but is distant and the mother, Susanne, seems to love the film.

“She was an abused woman,” Moselle says.

“I mean she was, there was a lot of mind control in that family and fear, and I think once she was deep in the situation there (it) was very hard and it was difficult how to figure out how to get out of it. Thankfully her children grew up and I feel like they’re the ones who really changed things for her.”

It is astounding the kids are so together and level-headed; they are now all pursuing or holding down creative jobs.

“It’s been amazing (but) the first thing that I noticed when I met them was how driven they were, a drive and determination that I hadn’t seen before,” she says.

“That’s why initially I wanted to be friends with them and help them because initially, for the first eight months, I didn’t know their backstory, I just thought they were just great kids.”

The Wolfpack is on limited release from August 27.