Tanna takes Vanuatu villagers to the world

The Pacific island nation’s first film — based on a true story — has received international praise.

There have been films shot in the South Pacific archipelago Vanuatu but not films of Vanuatu.

The Australian cinematographer of Mad Max: Fury Road, John Seale, made his directorial debut with the forgettable 1990 film starring Mark Harmon, Till There was You, and the only unforgettable moments of 1980’s The Blue Lagoon — the shots of the titular location — were filmed in Vanuatu’s Champagne Bay.

The new Australian film Tanna is not like those romantic visions of an island paradise.

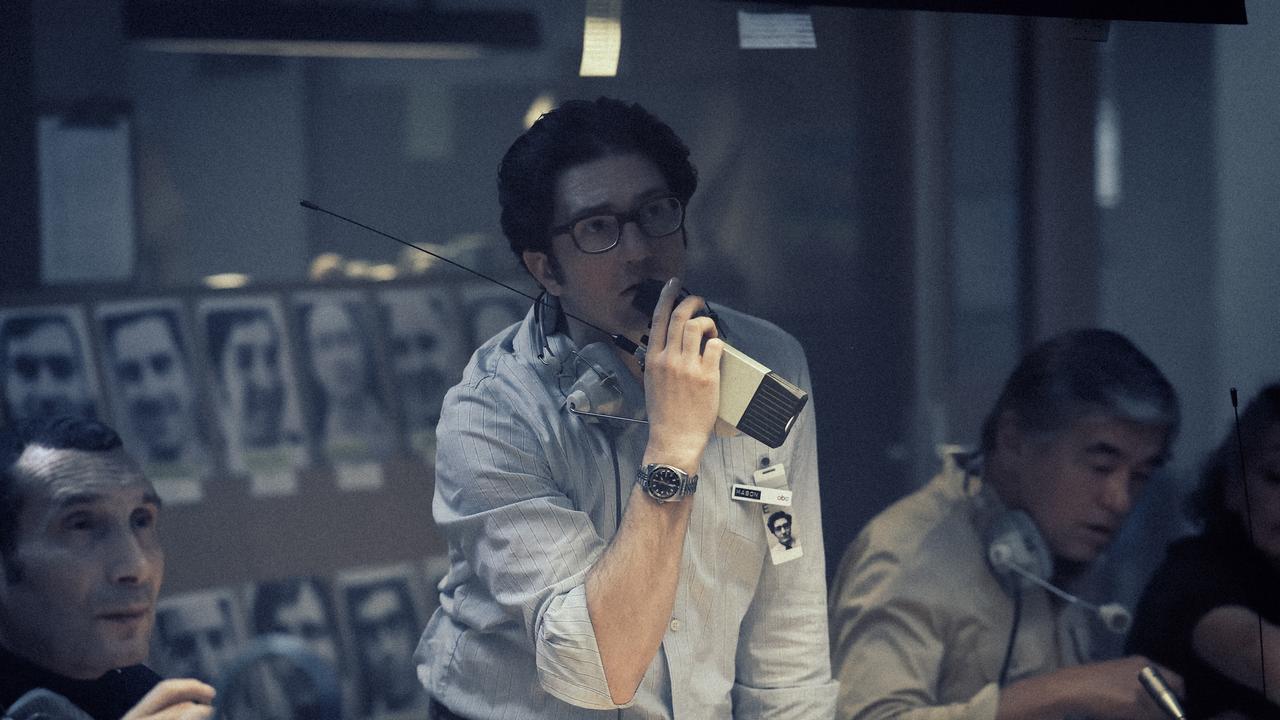

Bentley Dean and Martin Butler’s feature film is about the Yakel tribe of the Vanuatu island Tanna. It’s made by them and is very much their film.

The 200-odd highland villagers who feature in the tribal love story feature in the film in “our natural way of doing things, according to our natural roles”, says the film’s consultant, chaperon and the only villager who speaks English, “JJ”.

“To us it was not acting, it was doing what was real,” he says. “There is nothing difficult at all because we were performing what we were used to in our daily life.”

The feature is being viewed as the first feature film made by Vanuatu despite being, strictly speaking, an Australian-funded film. And the Yakel people are not only immensely proud, they adapted to the process in a fashion that ensures the film is something beyond mere cultural oddity.

That is due partly to Dean’s seven-month immersion as his family (including children aged two and four) lived in the village and developed a tale fit for film (which was adapted from an intertribal stoush over a young romance in the 80s).

When it came to filming, the camera was not a distraction for the villagers, Dean says.

“People just got it. Even in the really big scenes, with 100 to 150 people gathered, JJ would say, ‘Whatever you do, don’t look at the camera,’ and ‘This is the emotion of the moment, or here’s the focus of the moment,’ ” he recalls. “They were amazing; they would follow the direction to a T.”

Their professional attitude led to a film that has been embraced, already winning the critics week prize at the Venice film festival and a special commendation at the London film festival. And it has elevated the film beyond being a worthy but dull ethnographic exercise.

“Definitely,” Butler agrees. “We were very conscious of trying to avoid something that was ethnographically pure but not a great cinema experience. We wanted it to be really engaging and really emotional and hitting most of the markers you want to hit for a cinema feature with the big score. The big emotional moments are there because we want responses.”

And it is definitely not a documentary? “We don’t want an audience to think they’re going to be subjected to a documentary experience,” he says.

“We wanted them to go ‘Wow’, and be engaged, and for the tears to come. And this is a film to be experienced in the cinema. We got our recordist to record in 5.1 surround sound so when we’re on top of the volcano, you know you are at the volcano.

“And similarly with the big dances that happen, you are at the dance and they’re using the earth as an instrument, so you feel it.”

Dean and Butler previously made the acclaimed indigenous documentary Contact and the ABC series First Footprints. Dean was between jobs, as was his wife, when he decided to return to Vanuatu to live for a period with his family.

Dean, who was one of the original “contestants” on the 1997 ABC TV travelogue series Race Around the World, wanted to return to Vanuatu after reporting a story about a cargo cult for SBS’s Dateline a decade ago.

“I found myself on the lip of a volcano discussing geopolitics with a chief there and thinking, ‘This is amazing, I’ve got to find an excuse to come back, stay longer and learn more,’ ” he says.

JJ says the Deans and Butler — who flew in and out — were made to feel welcome. “Yeah, every night we (all) have kava,” he says, smiling. “They shared our food, lived with us, shared our huts.”

The crew’s immersion extended to editor Tania Nehme editing the film for six weeks in a bamboo hut on the island, Dean recalls, “in extraordinary circumstances but it was brilliant because we could show the villagers the scenes and give them an idea of the process, and it led to new scenes”.

The tribe hosted the world premiere in their village only weeks after Cyclone Pam devastated Vanuatu in March, and weeks before five villagers accompanied the film to its screening at Venice.

They love the film, JJ says, because they feel it is their film. “In all the decision-making with the story, we all discussed and consulted together, which is our normal way of making decisions.”

Dean is just as happy as he continues his own eclectic screen career. He doesn’t seem like the type to want to make an inner-city romantic comedy but he says, laughing, that he’s “open to anything”.

“It’s a luxurious position to be in,” he says of his career. “Since (Race Around the World) I haven’t been in a real job. It always has been the fortunate position of going, ‘I’m really interested in this, wherever it is happening in the world, so I’ll use my skills to turn it into a story and pay the rent.’ ”

Tanna is screening in selected cinemas, see facebook.com/TannaMovie.