Peter Craven’s top 15 book-to-screen adaptations

From Ben-Hur to Harry Potter, watch and rewatch the movies made of your favourite books for a whole new perspective.

It’s easy to forget how intimate the connection between books and films is, although it dominates the world of culture and entertainment. Think of Harry Potter. JK Rowling had the extraordinary experience of her books being filmed more or less as they were coming out. They were filmed with a fidelity we tend to reserve for Dickens and Shakespeare, and they had resplendent British casts – Maggie Smith, Richard Harris, Alan Rickman – that burnt into the minds of the millennial kids who saw them.

Harry Potter is in some ways a special case because Rowling took the world by storm with her combo of wizarding and boarding-school adventure, but we forget how much the book calls the tune with films.

If Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz are the great popular film classics of the 1930s, it’s worth remembering that they were popular books before then. People read Gone with the Wind and they saw Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O’Hara and Clarke Gable as Rhett Butler – or they did it the other way round. Either way, they experienced book and film as versions of each other.

This used to irritate Alfred Hitchcock whose version of the John Buchan thriller The 39 Steps is quite different from the original. He was irked by having to follow the basic plot of a contemporary bestseller like Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca even though anyone who reads it is likely to do so with the faces of Joan Fontaine as the unnamed narrator, Laurence Olivier as Max de Winter, and Australia’s Judith Anderson as Mrs Danvers before their mind’s eye.

When there are later versions the Hitchcock will be thought of as the “original” that cannot be equalled.

Something similar will be true of adaptations of le Carré novels. People who were stunned by what Alec Guinness did with George Smiley in the famous ITV adaptations of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and Smiley’s People – le Carré himself said Guinness had transformed the character – were less impressed by Gary Oldman.

It’s a complex cultural crossover. Hitchcock told Francois Truffaut (director of Shoot the Pianist) that Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment meant far too much to him for him to ever film it. On the other hand, The Grapes of Wrath was filmed by the great John Ford and some would rank it higher than the much-admired John Steinbeck novel it derives from.

Steinbeck has been lucky in his film adaptors. Elia Kazan (of A Streetcar Named Desire fame) made East of Eden with James Dean. Of Mice and Men was filmed by Lewis Milestone in 1939 but that fable has withstood a lot of versions. (A few years ago you could see in cinemas a stage-to-film version with James Franco looking after Chris O’Dowd as poor Lennie.)

Film has extraordinary authority because it has been a dominant popular medium for so long. You may have seen Spencer Tracy in The Old Man and the Sea long before you read Ernest Hemingway. Or you might put your money on Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre and still have a dominant image of the moment when Joan Fontaine as Jane meets Orson Welles’ extraordinary gargoyle of a Rochester. (In fact, it doesn’t matter which you encountered first because they are equally vivid.)

That’s true of some of the greatest film versions of novels like the post-war films of Dickens by David Lean: his Great Expectations with John Mills as Pip and his Oliver Twist with Alec Guinness as Fagin. Sometimes director, book and film seem made for each other. Was that true of Peter Jackson and The Lord of the Rings?

It’s certainly difficult to imagine a better Gandalf than Ian McKellen, a better Aragorn than Viggo Mortensen, a better Galadriel than Cate Blanchett. It’s interesting that the position of Tolkien which had already been established by the hippie generation was cemented by Jackson.

There are, of course, always degrees to which the film version works to broadcast and effectively complete the canonisation of the books. C.S. Lewis’s Narnia sequence was already culturally secure when the movies started to be made (in the wake of The Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter). While the films couldn’t have done any harm, they were secondary.

And if it’s true, as a well known publisher said to me, that Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials sequence was the so-called children’s book rivalling C.S. Lewis in literary quality, the film of The Golden Compass – despite Nicole Kidman in the cast, and Tom Stoppard working on an early version of the script – was not the equal to Pullman’s anti-clerical, bleakly atheistic masterpiece. Even so, Pullman’s writing is inherently dramatic, as the 2019 television adaptation of His Dark Materials – with Ruth Wilson as Mrs Coulter – showed with bells on.

The relationship between book and film is part of the essence of our culture and maybe for that reason is difficult to get in perspective.

Recently, during lockdown, I watched again the greatest of the 1950s Hollywood spectaculars, Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus. The turbulent saga of the slave revolt against the Romans may be the film over which Kubrick had least control, but it remains the greatest example of those biblical and Roman spectaculars that were both popular and prestigious.

The powerful, literate screenplay by Dalton Trumbo (one of the martyrs of McCarthyism) was from a novel by Howard Fast. Spartacus was clearly an attempt to spectacularise and Hollywoodise a radical vision and the closing moments – where each of the former gladiators says “I’m Spartacus”, and then Spartacus himself is crucified – is clearly an attempt to endow a Marxist vision with Christian resonance.

The film plays brilliantly on a range of familiar types, especially in the resplendent supporting cast. Olivier played Crassus at around the same time he was playing Shakespeare’s Coriolanus and he captures with extraordinary intensity the patrician politician at the edge of fascism. And in a perfect dialectical fit, Charles Laughton plays Gracchus, tribune of the people, as a suave Labour-style politician with a cynicism that does not quell the impulse to compassion. Both performances are remarkable bits of acting, and yet it’s clear that Kubrick’s masterpiece could not exist without its novelistic original.

Charlton Heston plays the title role in Ben-Hur, the film directed by William Wyler and derived from the novel by Lew Wallace – subtitled A Tale of the Christ – which I read at the same time I saw the movie as a child.

It’s a more conventional film than Spartacus and very focused on the grisly glamour of the famous chariot race as well as the trappings of galley slaves, crucifixion, leprosy and the never-glimpsed face of Christ who is always seen from behind.

Ben-Hur had been a famous silent film and a stage show before that. It is a rattling yarn, and watching Wyler’s version feels like you are experiencing the ideal form of the story.

Clearly this gets trickier with a modern literary masterpiece such as Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago filmed by David Lean at the height of his commercial dominance in the 1960s (immediately after Lawrence of Arabia). It’s also true that Robert Bolt’s script is very eloquent and Julie Christie is powerfully alluring as Lara.

The stakes are raised quite a bit when we come to Visconti’s film of the greatest of 20th-century Italian novels, Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s The Leopard.

Burt Lancaster is a staggeringly grand realisation of the old prince, Fabrizio, and Alain Delon as Tancredi and Claudia Cardinale as Angelica seem to have stepped from the pages of the book by some miracle of empathy. This is not to deny that Visconti adapts as he sees fit, ending the action with the ball. It’s simply that the spirit of the book receives its ideal translation so that we feel the same source inspires both.

It is also true of Visconti’s version of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, the story of the ageing Aschenbach’s flirtation with the image of a teenage boy. It doesn’t matter that Visconti has appropriated Mahler’s music (to stand in for Aschenbach writing). Björn Andresen is the boy of a shared world’s dream. Dirk Bogarde as the terminally frail Aschenbach gives us one of the greatest performances in the history of cinema.

Equivalent artistry is rare but it exists. What Kubrick did with Nabokov’s Lolita is different, but James Mason as Humbert, Shelley Winters as the mother and Peter Sellers as Quilty are incomparable.

Not long ago I watched Anthony Minghella’s film of Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient.

I had reviewed the book and had been somewhat scornful of it as a film. But for the first time in decades I was impressed by the variegation and dramatic vivacity of the film and the brilliance of the central performances from Ralph Fiennes, Juliet Binoche, Kristin Scott Thomas and Colin Firth: all of whom became famous though they were then in their 30s.

It was clear that something special was happening on film and that this presupposed a literary original.

It doesn’t always work. Milo O’Shea as Leopold Bloom and Barbara Jefford as Molly Bloom act beautifully in Joseph Strick’s 1967 film of James Joyce’s Ulysses but it is no equal to the greatest book of high modernism in the English language.

Volker Schlondorff made quite a good film of the least characteristic part of Proust, Swann in Love, with Jeremy Irons in the title role, but the standout performance was from an ageing Delon as the Baron de Charlus. Harold Pinter wrote an impressive script of Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu (Remembrance of Things Past) but it was never filmed. Visconti also wanted to film Proust but no doubt would have been tempted to do it in 50 hours (the moment of longform television had not yet come).

It did come, however, for Rainer Werner Fassbinder in Berlin Alexanderplatz, that extraordinary depiction of crims in pre-Hitler Germany. The novel by Alfred Doblin is influenced by Joyce in style but with a very un-Joycean dramatic momentum. Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz is at least equal to its original, and its Ring Cycle length of 15-odd hours sustains extraordinary performances. Susan Sontag was right when she said that Gunter Lamprecht as Franz Biberkopf, that piteous blind ox of a man, had given a performance as good as anything by Emil Jannings of Blue Angel fame.

This is the zenith of the realisation of the literary as film but it underlines what we have always known: that books and films will forever be saddled together.

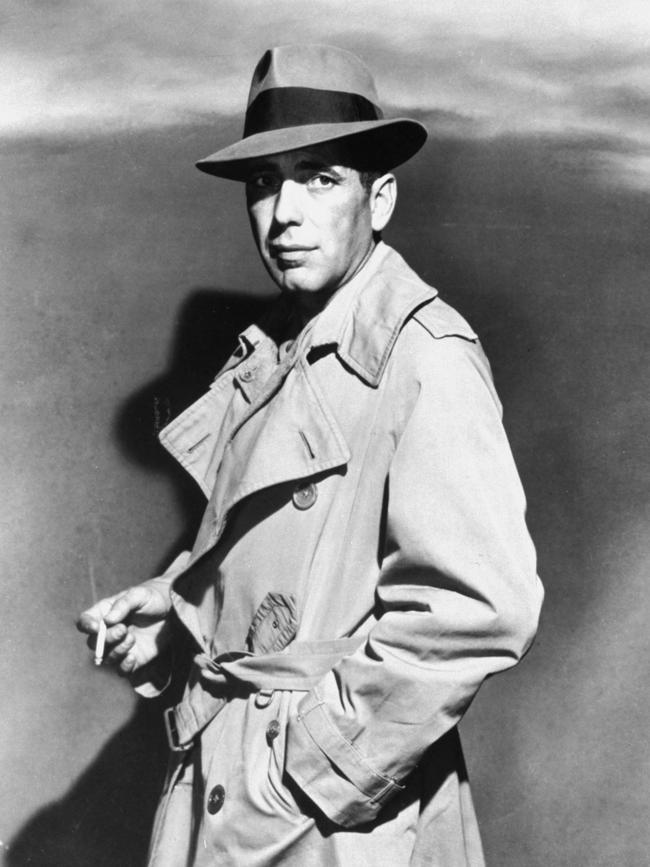

We think of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie and we think of Maggie Smith. We think of The Maltese Falcon and there is Humphrey Bogart.

They are archetypal elements in a dreamworld we will always inhabit.

BY THE BOOK: PETER CRAVEN’S 15 FAVOURITE ADAPTATIONS

1 Witness for the Prosecution

Billy Wilder did what he liked with the Agatha Christie story but she admitted it was the finest version of her work ever done. Charles Laughton and Marlene Dietrich at their most riveting.

2 The Gospel According to Saint Matthew

Pasolini filmed a pile of literary classics (Boccaccio, Chaucer) but this scriptural one outshines them all.

3 Tom Jones

Tony Richardson’s empathic adaptation of Fielding’s 18th-century romp with the young Albert Finney.

4 Don Quixote

The first and arguably the greatest of all novels directed by Grigori Kozintsev and starring Nikolai Cherkasov (the legendary Russian actor who played Ivan the Terrible) as the Don.

5 The Third Man

While all screen adaptations of the Graham Greene story work, nothing equals Orson Welles as Harry Lime.

6 The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith

Tom Keneally’s novel in a towering film version by Fred Schepisi with Tom E. Lewis as the Aboriginal bushranger.

7Letter to an Unknown Woman

This is the great Max Ophuls’ one American film that rivals the sweeping poignancy of his French masterpieces. With Joan Fontaine and Louis Jourdan.

8 Far From the Madding Crowd

Directed by John Schlesinger, a flawless transposition of the Hardy novel perfectly cast with Julie Christie, Alan Bates, Peter Finch and Terrence Stamp. It has all the power of the novel.

9 Diary of a Country Priest

Bresson’s masterpiece about a frail, alcoholic, saintly priest from the Georges Bernanos novel.

10 Dangerous Liaisons

Laclos’ deadly 18th-century novel is brought brilliantly alive in Stephen Frears’ version with John Malkovich and Glenn Close at their most wicked.

11 Brokeback Mountain

Annie Proulx’s fine story is the basis but Ang Lee’s film with Heath Ledger giving a performance for the ages is superior to it.

12 Sense and Sensibility

The finest version of Jane Austen ever made with a script by Emma Thompson. She and Kate Winslett are superb as the two sisters and so are Hugh Grant and Alan Rickman in support.

13 The House of Mirth

Terrence Davies’ masterly adaptation of the Edith Wharton novel with Gillian Anderson giving the performance of her career.

14 The Silence of the Lambs

Anthony Hopkins and Jodie Foster give a dazzling realisation of Thomas Harris’s genius psycho and the woman who gets inside his mind.

15 The Prisoner of Azkaban

The best Harry Potter book happens to be the best movie directed by the great Alfonso Cuaron.