Munzi’s Dark Souls captures reality of Calabrian mafia life

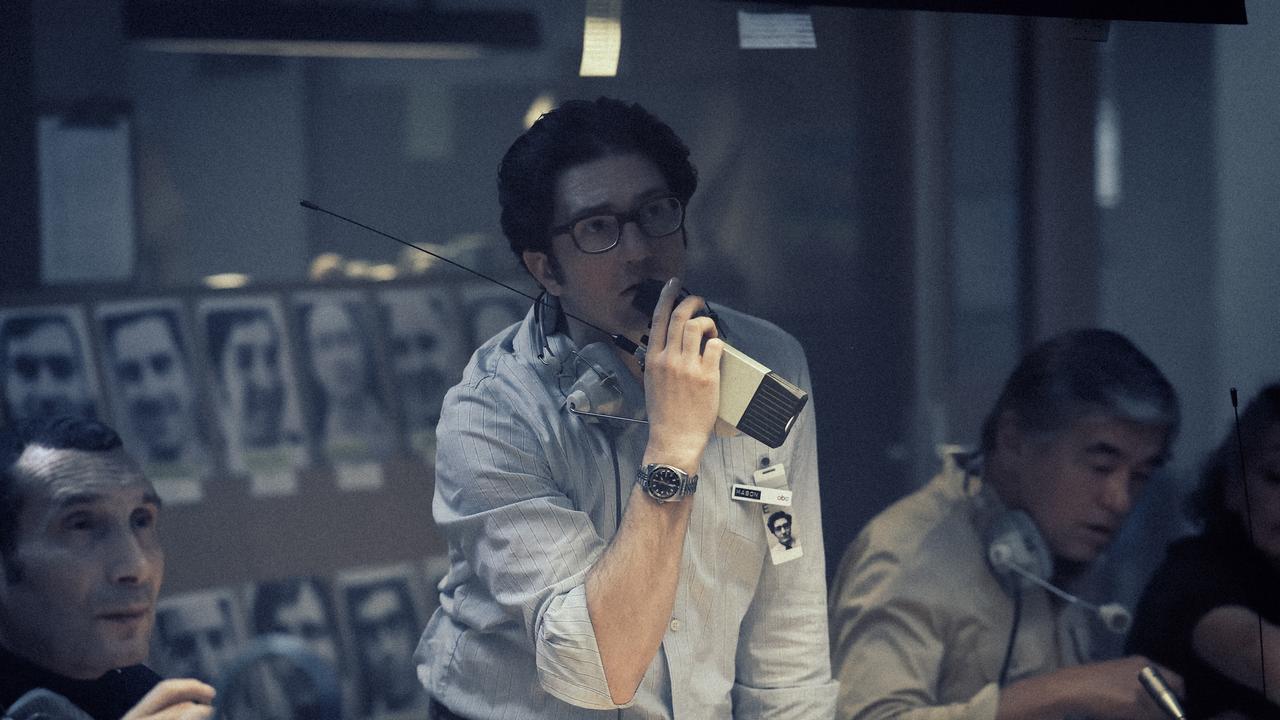

Francesco Munzi’s award-winning Black Souls deromanticises the mafia.

Francesco Munzi has directed an excellent Italian film about the mafia, yet he despises his subject.

“I don’t like the mafia,” says the director of Black Souls (Anime nere). “For me, it’s important how to talk about the mafia. Generally in the movies there’s a romantic and epic vision of the crime of the mafiosi. And in my movie I try to change this vision to show the tragic effects of the crime.”

Munzi’s third feature is a neorealist take on the mafia movie, based on Gioacchino Criaco’s novel of the same name about the Calabrian mafia and the lesser-known — at least relative to the Sicilian Cosa Nostra — Ndrangheta crime syndicate.

Munzi says he was struck by the novel and “especially by the not-so-romantic vision”.

“And I liked to show not only the war between two crime families but the war inside the families, and speak about the contradiction inside the crime family,” he says.

The three sons of the Carbone clan represent the generational and cultural differences within one family and within crime syndicates. Luigi (Cinema Paradiso’s Marco Leonardi) is the hard man setting up and scoring on cocaine deals from Amsterdam. His more rational business partner Rocco (Inspector Montalbano’s Peppino Mazzotta), flushes the cash through more respectable businesses from his base in Milan. And the eldest, Luciano (Malena’s Fabrizio Ferracane) is on the outer, preferring to work in the countryside like his ancestors, away from the crime business — yet his son Leo is itching to join the syndicate.

Munzi says the differences between the three brothers are stark and “that is the heart of the movie”.

So, Black Souls is more a family drama than a mafia drama? “Yes,” Munzi says happily. “It’s a family drama in the crime genre.”

Possibly as a result, it has won more acclaim than the straight-up crime dramas that have tended to overwhelm the subject. A phenomenon of enormous interest that has also caused a great deal of pain to Italy has been humanised somewhat by Matteo Garrone’s excellent 2008 film Gomorrah and the subsequent television series Romanzo Criminale.

But Munzi’s movie takes the realism to another level. The Calabrian dialect features so strongly in the film that it was screened with subtitles in part of Italy. And it performed far better in southern Italy, where audiences could more readily identify with the setting and the issues. Munzi’s decision to mix his actors with non-professional villagers may also have resonated.

“What was very shocking was the degree of realism … in a fiction movie, because it used real people from the village,” he says. “It’s a film shot with the population of the little village and showed the dialect, so it’s something very original for Italian cinema.”

Munzi’s screenplay, written with Maurizio Braucci and Fabrizio Ruggirello, is not a true story, he says, “but it’s very similar to a true story. I cheated a lot from (Criaco’s) book because the book is located in the 1970s and 80s and I bring the story to these days,” he says. And the book also follows three friends, who become Black Souls’ three brothers.

His co-screenwriters belong to the area in which the film was shot. The villagers accepted the project, particularly after Munzi told them he wanted to investigate “not the good things”.

“They feel they were able to speak with me about themselves, so they felt assured in that way,” he says. “We made an agreement that we would be a fiction film without the names, but I said I want to tell the truth.

“We did the film together and I had perfect freedom, but the freedom also became something like a social experiment to me, making the movie.”

Their only disagreement came with the film’s conclusion. Oddly, the locals in the film wanted the mafia and clan wars depicted in it to be ongoing.

Munzi’s previous films, Saimir in 2004 and The Rest of the Night in 2008, both assessed a big subject — immigration — in a humanist style. Black Souls seems to confirm his method.

“When I face a really big topic like immigration or the mafia, I need to feel for the topic from a particular vision, something I can know well, like a relationship in a family,” he says.

“So in all my movies, the characters come from something more particular, like the relationship between brothers. So in this case, I talk about a big topic like mafia with a vision of a human relationship, the feelings inside the family.

“Also that is what the audience could relate to.”

They have related. Black Souls won nine awards from 17 nominations at this year’s David di Donatello Awards in Italy, including best film and best director. It has also been sold into many territories and will be screened during next week’s Italian Film Festival in Australia.

For what he describes as “a little movie, made like a documentary”, it has been an overwhelming success.

“I’m very happy and very surprised,” Munzi says, adding however that the reality of the subject is also hard.

“The film is very full of pain, it is quite a romantic view of Italy so I know it could also be hard to show this reality to some Italians,” he says. “It’s painful but it’s an honest representation.”