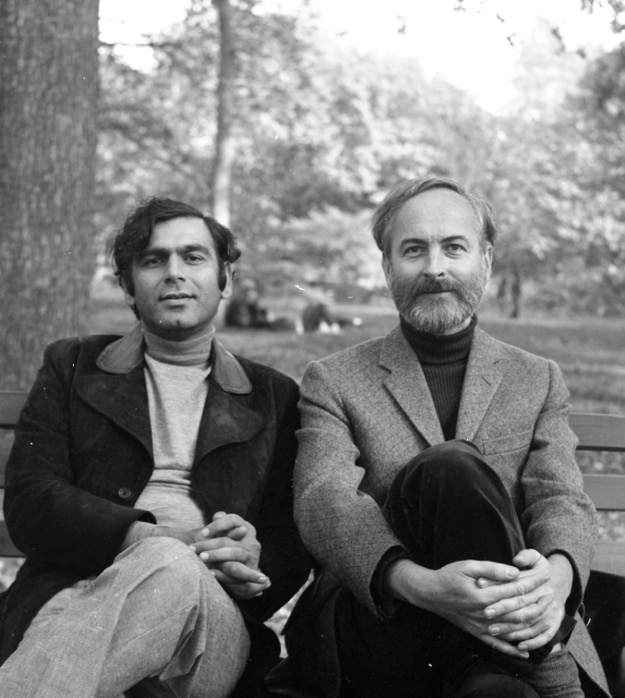

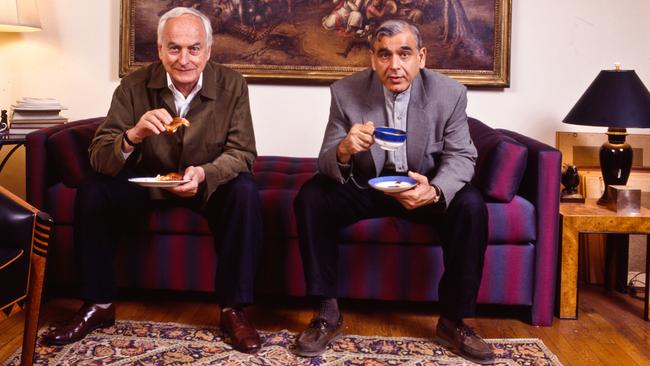

Kings of the silver screen: Merchant and Ivory

A new documentary charts the lives, and love, of filmmakers James Ivory and Ismail Merchant, who have left an indelible mark on film history.

American director James Ivory and Indian producer Ismail Merchant have left an indelible mark on film history with movies including A Room with a View, Howards End and The Remains of The Day.

In a new documentary, Merchant Ivory (named for the company the pair established in 1961), actor Helena Bonham Carter notes how she expected the older Ivory to pass away before his business and life partner, who suddenly died in 2005 at the age of 68.

“If you’d asked me years ago, right at the beginning, when I met them back in the 18th century, who was going to last the longest, it wasn’t going to be Jim,” says Bonham Carter, who starred in A Room with a View and Howards End, in the film.

“He was an introvert and he was shy, but he seemed the oldest in a way, the most mature. Ismail should never have died when he did – but it’s not surprising, because he just sort of exploded or imploded because the stress levels (he was under) were just unsustainable.”

Merchant had been tireless in raising the finance for their grand but surprisingly low-budget films, an effort covered extensively in the documentary. Director Stephen Soucy, who had attracted Ivory’s attention with his short film about Merchant Ivory’s music, notes how Ivory has been rigorous in promoting the new film, which screens this week as part of The British Film Festival.

The Australian tells Ivory, 96, how a 96-year-old friend, to keep her mind lucid, does The New York Times crossword every day.

“I don’t do the crossword, but I read The New York Times every day on my phone,” he says. “I recently published a nonfiction story and you can read about it in The New York Times.” As for his longevity, besides reading and writing he says he has a good appetite and sleeps well.

In 2018, Ivory became the oldest person to win an Oscar when at 89 he took out the award for best adapted screenplay for Call Me by Your Name. (Ann Roth tied with him when she won the 2021 costume design Oscar for Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom at the same age.) Ivory had previously been nominated three times and had never won but of course was grateful.

“Who wouldn’t want to have an Oscar? I wrote the screenplay, but I didn’t make the film, and I wasn’t present at the making of the film, though I like it very much,” he says.

He notes how Ruth Prawer Jhabvala had twice won Oscars for her EM Forster adaptations A Room with a View and Howards End and he is keen to praise the writer who wrote 23 screenplays for Merchant Ivory films. She died in 2013 aged 85.

“Having a novelist and short-story writer as a screenwriter was the key to our success with adaptations,” Ivory says.

“Her fiction was far more important to Ruth than her screenwriting, so she was the right person to adapt those novels into screenplays.” She felt Ivory was the right person to direct them and once told him that Henry James was writing for him and that he was meant to direct her adaptations of The Europeans, The Bostonians and The Golden Bowl.

Ivory directed her adaptation of her Booker Prize-winning novel Heat and Dust, which also screens at the British Film Festival in a new 4K version.

One of Ivory’s greatest coups was his discovery of acting talent. As well as Bonham Carter, he essentially launched the careers of Emma Thompson and Hugh Grant, who provide hilarious interviews for the film.

“I was working in comedy and I wasn’t sort of, ‘Oh, I must do this’,” Thompson recalls of her casting in Howards End. “I had nothing to do with any movie makers. Actually, I was quite a militant feminist and I wasn’t interested in being told what to do by men. But when I heard that Jim and Ismail were making the film, I had a very visceral reaction to the character of Margaret Schlegel, because she reminded me so much of me in the sense that she was, you know, interfering and loud and opinionated and wanted to make the world a better place.

“Tony (Anthony Hopkins) had just become more famous than God by being in The Silence of the Lambs. And so, in fact, the first time I met Tony, I had to give him a note from my mother, which said, ‘This is my daughter, Emma. Please don’t eat her,’ because of the ‘Hannibal Lecter’ of it all, which made him laugh.

“Tony reminded me of my dad, because he was from a very poor family, and he’d come to this strange branch of the performing arts, just on his knees. It made him completely pure and natural and he had the most incredible energy and tone. It was funny, because I remember us coming back from LA, I think it was after The Remains of the Day, and he said, ‘Oh, it’s very funny. Everybody thinks we’re having a big, passionate affair’. I said, ‘Oh, really? How odd’. I suddenly realised that we had such a strong connection and bond that that was what was had been assumed. But nothing could have been further from our minds.”

Grant’s first film was the gay love story Maurice which was released at the height of the AIDS epidemic and figures prominently in the film. Merchant Ivory had just experienced huge success with A Room with a View and although Merchant wasn’t keen, Ivory insisted this was their chance to make the film.

Grant recalls initially not being keen on doing Maurice and meeting Ivory to discuss the part. He was living with his brother who said, “Don’t be ridiculous, you have to go. They’re classy.”

Ivory was insistent, as his A Room with A View star Julian Sands had pulled out of the film, which was based on another EM Foster novel, written in 1914 and only published in 1971 – after his death – because of its gay content. The film co-starred James Wilby.

Ultimately, Grant says, “It was a great part, a great novel and a great filmmaker, great co-stars. It was very easy to say yes. And apart from anything else, it was my first film, I mean a dazzling prospect.”

In one excerpt that didn’t make it into the final Merchant Ivory edit, Grant recalls attending Maurice’s Venice Film Festival world premiere where he had a clothing mishap.

“We go to the huge gala premiere, we are seated at the front of the circle and the drill is that at the end of the film, if they love it, everyone claps, and then you stand up to take the applause and say, thank you very much,” he says.

“Anyway, they did love it, and we did stand up. But there was something I hadn’t realised. I was wearing a suit for the special occasion. I only had one suit. I wasn’t very rich, and it was too small for me. I’d gotten too fat for it.

“So during this long film, I’d undone the top button of my trousers, which had then kind of undone the zip without me knowing. So there we are at the end of this gay film. I stand up to take my royal bow to everyone and I realise my trousers and fly are completely undone. It was a bad look. James Wilby and I won the joint best actor prize, which was a big bit of rocket fuel under our careers.”

Ivory stays in contact with most of his actors, also including Vanessa Redgrave and Greta Scacchi, who are interviewed in the film. “I liked Greta immediately and she got the job from the start for Heat and Dust,” he recalls. “I wasn’t interested in anyone else.

“Heat and Dust was shot in Hyderabad and it was so hot that we stopped and came back to it later. It wasn’t an easy film to make as we didn’t have enough money but as with almost every film, Ismail found the money and we finished it.”

He is “thrilled” the film is being given a new life and notes that the Cohen Media Group, which owns 30 films from the Merchant Ivory library, have been restoring and re-releasing many of the titles. One of Ivory’s favourites, 1972’s Savages, is being restored and re-released next year.

Ivory, as an American from a well-heeled background, might seem a strange force behind reviving the British period drama, but his humanistic films have exerted a huge force in the creation of movies such as Atonement, Gosford Park and a slew of Jane Austen adaptations, including the Thompson-scripted Sense and Sensibility, for which she won an Oscar. In Merchant Ivory she notes how Prawer Jhabvala helped her write the screenplay.

In reviewing his filmography, Ivory likes to point out that he made many of his early films in India – Satyajit Rey was his mentor and remains his favourite filmmaker – and that he also made films in other countries including the US and France where Naomi Watts starred in The Divorce.

Surely his legacy will also include his trailblazing with Maurice. “That wasn’t the first gay film we made,” he notes. “Our first film was for the BBC, Autobiography of a Princess starring James Mason. He played a gay man way back in 1975 and there was The Bostonians with Vanessa Redgrave in 1984.”

In 2021, Ivory published a memoir, Solid Ivory, in which he writes about his relationship with Merchant, the personal details, the affairs. “After the book was published I had my final interview with Jim for the film,” recalls Soucy. “I told him I was going to ask personal questions and Jim was 100 per cent game.”

Even in the book Ivory has been careful. “Some of Ismail’s conservative Mumbai Muslim family were still alive and I was concerned about them reading it. I didn’t want to cause any unhappiness or grief,” he says.

Colourful, outgoing and jovial, Merchant always ensured his cast and crew were well-fed – lots of Indian curries – even if sometimes they weren’t yet paid.

Ivory’s final film following Merchant’s death was The City of Your Final Destination, the company’s fourth film starring Anthony Hopkins, after Howards End, The Remains of the Day and Surviving Picasso.

While in archival footage Hopkins says The City of Your Final Destination was the most enjoyable film he’d been in for many years, he ended up suing for nonpayment of his salary.

“Well, he got paid, so that lawsuit went away,” Ivory says.

“I talk to him if I have a reason to talk to him, but he is not an intimate of mine.”

Merchant had been passionate about the film, Ivory notes with some emotion, adding that they had gone together scouting for a house in Argentina where the film was shot.

What does he miss about Ismail? “I miss everything, everything,” he replies. “He was just a vital life companion. I hope you can get a sense of that in the film, how connected we were, starting with our meeting on the steps of the Indian Consulate, and then seeing all of these chapters in our lives in the film. How can I not miss everything about Ismail? He was such a character.”

Would Ivory like to direct a movie with actors again, or does he think that ship has sailed?

“Well, I’m getting old and I don’t know I could be insured. But sure, maybe. A hundred years with Merchant Ivory, that’s what they could put on the ads.”

What might be his epitaph when he leaves this mortal coil? “I think I’ll be missed because I’ve amused all of my friends. But it’s the films that will last and they will stay around forever.”

Merchant Ivory is in cinemas as part of the British Film Festival.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout