One of the pleasures, therefore, of Apocalypse Now: Final Cut, released to mark the 40th anniversary of the film, is the freedom to spend more time with moments that, on first viewing, may have slipped by in anticipation of what was to come.

As with the 1902 novella on which it is loosely based, Joseph Conrad’s Belgian Congo-set Heart of Darkness, Coppola’s Vietnam War epic is a full-steam, headlong charge to a dark place, geographically, physically, mentally, morally.

We know from scene one/page one that we are heading there. As with Willard and Conrad’s Marlow, the only question is whether we will make it to the end alive.

The scene that stunned me on this viewing happens early on. Willard is called into a room, greeted by army officers (including a young Harrison Ford) and briefed, eventually, on his mission. The briefing is indirect and borders on uncomfortable for all involved.

Lunch is served: large plates of roast beef and fried shrimp. The camera moves to the food and plates and cutlery quite often. The dialogue is heard but not always seen. The voices come as we look at another face, or at the laden table.

And one man, in civilian clothes, does not speak at all. Yet we see his face a lot. His tie is loose. He smokes. We do not know why he is there. He looks out of place.

Yet when finally he does speak he has the last word on Kurtz. Again, we know what he says. “Terminate with extreme prejudice.”

This time around, though, it was not that sentence that grabbed me — I knew I would hear it — but every second that led up to it. This, I thought, is a masterclass in filmmaking, in front of me right here and now.

We also know the backstory to Apocalypse Now. Sheen, not the first choice for Willard (Steve McQueen, Al Pacino, Jack Nicholson and Clint Eastwood all said no; Harvey Keitel said yes but Coppola sacked him almost immediately), had a heart attack during the shoot.

Brando was significantly overweight, which hardly fitted the image of a decorated green beret, and certainly didn’t fit Conrad’s emaciated “eloquent phantom … not much heavier than a child”. He also didn’t learn his lines.

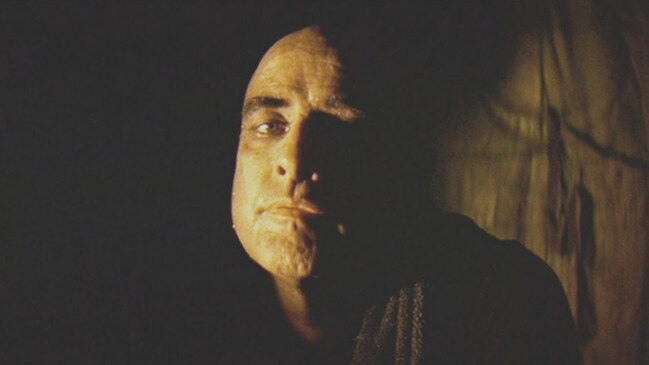

Yet who cares, when he does what he does on screen? The first encounter between Kurtz and Willard, when the target, his hand rasping over his bald dome, dismisses the assassin as an “errand boy, sent by grocery clerks to collect a bill”, puts us in the presence of a genius. It encapsulates Conrad’s Kurtz, a journalist turned ivory trader, as a blend of “wistfulness and hate”.

Coppola did consider shooting the movie in Cairns but chose The Philippines, partly because labour was cheaper. A typhoon rewrote the budget by destroying sets and equipment. Coppola almost went broke and the movie took almost two years to make instead of the scheduled five months.

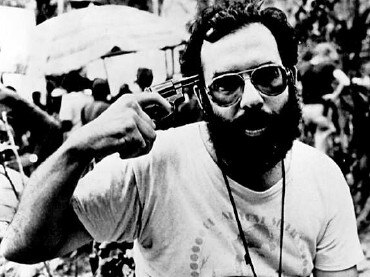

You can see all of this story behind the story in the riveting 1981 documentary Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse. The famous photograph of Copolla on set holding a gun to his head looks, in hindsight, like gallows humour.

The 1979 original was heavily cut at the studio’s insistence, though it still clocked in at 153 minutes. On release it won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and two Oscars, for sound and cinematography. Best picture, best director (Robert Benton) and best actor (Dustin Hoffman) that year all went to Kramer vs Kramer.

In 2001, Coppola released Apocalypse Now Redux, a 202-minute labour of love that reinstated almost all the cuts from 1979. The director said at the time that it was not the definitive version of the movie. That comes now, with Apocalypse Now: Final Cut, which runs to 183 minutes.

In the critics’ screening I attended, we were shown an introduction in which Coppola, now 80, speaks about the three incarnations of the film. The original suffered “annoying cuts to make it shorter”. He said the thinking at the time was “to make it as not weird as we possibly could”. Yet the passage of time would soon show that it was not weird at all: “Avant-garde art becomes the wallpaper of the future.”

The Redux edition was almost a payback for the cuts to the original. “It was the chance to put everything back.”

Now, the director believes, we do have the definitive Apocalypse Now. “It looks better than it ever looked and it sounds better than it ever sounded. It’s the one I recommend to you.”

The better picture and better sound is due to the incorporation of state-of-the-art film technology. For this reason, and for the sheer scale of what happens on screen, this is a movie to see in the cinema. The well-known scenes I mentioned at the outset, such as the choppers blitzing a village to Ride of the Valkyries, are close to overwhelming.

The final scene, paralleling the fates of brilliant Kurtz and a dumb water buffalo, is almost too harrowing and draining to watch. Here is Willard, in the lead-up to that moment, thinking about Kurtz: “He knew more about what I was going to do than I did. If the generals back in the Trang could see what I saw, would they still want me to kill him? More than ever probably. And what would his people back home want if they ever learned just how far from them he’d really gone? He broke from them and then he broke from himself. I’d never seen a man so broken up and ripped apart …’’

These voiceovers were written by Michael Herr, author of perhaps the best book on the Vietnam War, Dispatches (1977).

The hypnotic use of colour, of light and dark, real and psychological, is where Copolla pays homage to Conrad. This is from the opening pages of Heart of Darkness: “And at last, in its curved and imperceptible fall, the sun sank low, and from glowing white changed to a dull red without rays and without heat, as if about to go out suddenly, stricken to death by the touch of that gloom brooding over a crowd of men.”

Coppola has omitted some of the scenes that people questioned in Redux, such as Playboy bunnies trading their time for fuel.

He has, however, left in the scene that sort of stops the movie in its tracks for an extended period: a detour on to a French plantation by Willard and his boat crew. It’s possible he did so because it features a cameo by his son Gian-Carlo, who died in speedboat accident in 1986, aged 22.

I’m not sure what to make of this sequence. I need to see it again, and again. It is unusual, and hard to work out.

I think it goes to the “conquest of the earth” that Marlow talks about in Heart of Darkness, “which mostly means taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves’’. This drive, as old as humanity, “is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much”.

Apocalypse Now: Final Cut will run for about two weeks at select cinemas in all states. All I can say is go see it.

Some screenings will include a Q&A between Coppola and fellow director Steven Soderberg that was recorded at the Tribeca Film Festival in May. For me, this line from Soderberg sums it up. “I don’t know what to say, other than you gambled and you won.” He did and he did, and so did we. This movie, in all of its versions, stripped, bare or varnished, is a masterpiece.

Apocalypse Now: Final Cut (MA15+) 5 stars

Limited National Release from Thursday

We all know the never-to-be-forgotten scenes from Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) rising from the water like a river demon as he heads for his confrontation with Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando). Kurtz moving his almost supernatural head in and out of dark and light. Kurtz’s photojournalist disciple (Dennis Hopper) quoting bits of TS Eliot. Lieutenant Colonel Kilgore (Robert Duvall), shirtless, upright and obsessed with surfing as his troops duck for cover, showing that being able to keep one’s cool is no guarantee of sanity. The helicopters swooping over a village with both guns and Wagner at full throttle.