Films at Cannes festival reflect global unease

Festival entries depict societies racked by woes across Europe and the Middle East.

It’s generally believed that cinema reflects the world in which we live. If that’s true, the world, according to the movies screened this year at Cannes, is in a pretty wretched state.

Film after film depicted societies crippled by corruption, greed, violence and a complete lack of humanity. These grim portraits of dysfunction came from various sources.

In Beauty and the Dogs, a Tunisian film by female director Kaouther Ben Hania, a teenage girl is raped by policemen on a beach near the place where she has been partying; hospitals won’t admit her until she has reported the rape to the police — at the police station where her attackers are based.

One of the principal characters of three-part Algerian drama Until the Birds Return witnesses two men brutally bashing another man late at night but is too afraid, or lazy, to report it. The protagonist of Iranian film A Man of Integrity (winner of the Un Certain Regard section of the festival) is attempting to live a decent life by the principles he holds dear, but such is the extent of corruption all around him that he is unable to function.

Refugees attempting to cross the Serbian border into Hungary are greeted with bullets by racist border guards in Jupiter’s Moon, a fantasy in which one such refugee, despite being shot, recovers to float like some kind of eerie balloon above Budapest. In Turkish-born German director Fatih Akin’s In the Fade, neo-Nazis murder a Kurdish travel agent and his small son with a nail bomb, leaving his wife, Diane Kruger (best actress), to seek justice, first legally and then outside the law.

Bulgarian film Destinations consists almost entirely of scenes inside taxis traversing the streets of Sofia, scenes in which the troubles of passengers and drivers are exposed, including those of a schoolteacher who has become suicidal. In French film The Workshop by Laurent Cantet, a novelist teaching a summer writing class in a Mediterranean coastal town begins to suspect one of her students is a dangerous right-wing extremist.

Michael Haneke’s deliberately mistitled Happy End is a sort of sequel to his award-winning Amour. Again veteran Jean-Louis Trintignant plays an old man eager to end his own life, but this self-styled “snapshot of a bourgeois European family” has the subtext of a society riddled with greed and exploitation.

Loveless, leading Russian director Andrey Zvyagintsev’s latest, after his masterly Leviathan, won the Jury Prize. It focuses on a deeply selfish St Petersburg couple so filled with hatred for one another and so sexually involved with their new partners that they totally neglect their unfortunate 12-year-old son, whose sudden disappearance is the focus of a cold, brilliantly handled exercise in contemporary angst.

But perhaps the most extreme example of contemporary malaise is to be found in Ukrainian director Sergei Loznitsa’s A Gentle Creature, which is very loosely based on a story by Dostoevsky. Contemporary Russia, as depicted in this lacerating film, is a place of horror. The “gentle creature” of the title is an ordinary woman, played by Vasilina Makovtseva, who is attempting to get a food parcel to her husband, who is serving time in prison for an unspecified crime. The parcel is returned undelivered; the post office is no help, so the woman travels to the prison, a nightmare journey in which she encounters the dregs of society — drunkards, pimps, whores, rapists, crooked cops, you name it.

The film was shot in Latvia or Lithuania (both were reported as the location) because it could not be filmed in Vladimir Putin’s Russia, and its most chilling moment comes at the end when the unfortunate woman is taken away from a railway station waiting room to face an unknown fate — and the people packed into the room take no notice but simply sleep on, allowing more atrocities to occur.

The best of several French films in the festival was Jeune femme (winner of the Camera d’Or for best first feature), which centres on a brilliant performance by Laetitia Dosch as a young woman having difficulty fitting into society.

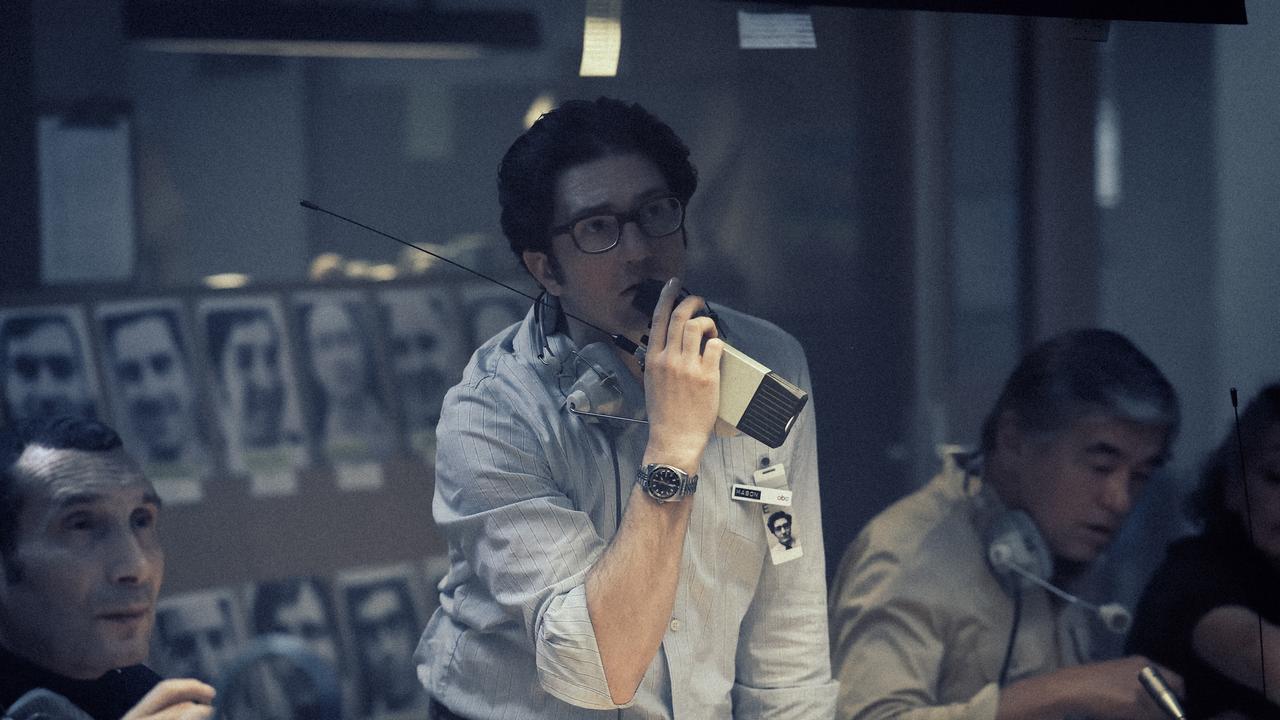

Michel Hazanavicius, who made The Artist, has fun with Redoubtable, a film about Jean-Luc Godard, the man who changed cinema, and how he became radicalised in 1967-68. Louis Garrel gives a great impersonation of Godard and Stacy Martin is a delight as his mistress/muse, Anne Wiazemsky.

Francois Ozon’s L’amant double is a delirious melodrama in which a young woman marries her shrink, only to discover he has a lustful twin brother. Jacques Doillon’s Rodin stars Vincent Lindon as the famous sculptor, and is pretty conventional in its approach, while Robin Campillo’s 120 Beats per Minute (Grand Prix) is a vastly overlong but passionate film about the AIDS crisis of the early 1990s and the politics that surrounded it.

One of the festival’s most enjoyable films — and there were some — was Noah Baumbach’s The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected), a superbly scripted and acted Jewish family comedy-drama set among the New York art world, with consummate performances from Dustin Hoffman as the family patriarch, Emma Thompson as his latest wife, and Adam Sandler and Ben Stiller as his sons. It’s such a shame that this Netflix Original production can be seen only via streaming and won’t appear in cinemas, where its pristine brand of smart comedy would be delightfully received.

I wasn’t familiar with the work of the Safdie brothers, Josh and Benny, but their latest, Good Time, is a frenetic thriller that takes place over a few hours in New York. Robert Pattinson gives his best screen performance to date in the leading role.

Less impressive, at least as seen in the work-in-progress screened at Cannes, is Scottish director Lynne Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here, a violent thriller apparently influenced by Taxi Driver, with Joaquin Phoenix (best actor) as the hit man who prefers to use a hammer rather than a gun.

Next to these films, Sofia Coppola’s remake of the classic 1971 drama The Beguiled looked positively tranquil with its story of a wounded Union soldier (Colin Farrell) taken in by a school filled with women teachers — led by Nicole Kidman — and girls. Coppola was named best director by the jury led by Pedro Almodovar. Farrell and Kidman were seen to better advantage in Greek director Yorgos Lanthimos’s challenging The Killing of a Sacred Deer, a family drama that intrigues and confronts for much of its length, and which shared best screenplay with Ramsay’s film.

The coveted Palme d’Or went to Swedish film The Square by Ruben Ostlund (Force Majeure), a black comedy about a smug but respected art curator who overreacts when his wallet and mobile phone are stolen.

It’s a film brimming with ideas and wit.

Kidman was awarded a special prize in honour of the 70th anniversary of the festival.