Australian Film Television and Radio School looks at bigger picture

Changes are afoot at AFTRS, but is it still our top talent nursery?

The national film school has come a long way since its inaugural students, Gillian Armstrong and Phillip Noyce among them, were part of the “interim training group” in 1973.

The Film and Television School became the Australian Film Television and Radio School in 1986 and moved from its once-rustic North Ryde digs to a new purpose-built facility at Sydney’s Fox Studios in 2008.

Now the school is undergoing another big transition after chief executive Sandra Levy stepped down after an eight-year stint, during which she instituted the AFTRS Open program, expanded the institution’s engagement with the industry and, perhaps most important, implemented the three-year bachelor of arts (screen) program. The new degree, stemming from the previous foundation diploma, most closely aligns with the kind of immersive education for a core stream of students that AFTRS was known for decades ago.

Neil Peplow, chief operating officer of the Met Film School in London and Berlin, and a former director of screen at AFTRS from 2011 to 2014, will replace Levy.

What kind of film school will he take over? Opinions vary. There is little doubt AFTRS has opened up — its courses have been prepared with greater industry consultation than previously — and particular streams are very successful. Its radio graduates tend to all walk straight into employment and its screen technicians are highly regarded.

AFTRS also has taken over, by default, some industry functions including research and industry engagement as the Australian Film Institute/AACTA vacillated and the industry’s development strands shrank with the Australian Film Commission’s departure.

But is AFTRS producing, as it did through the 1970s, 80s and 90s, the influential film directors of the future: the likes of Jane Campion, Rolf de Heer, Warwick Thornton, PJ Hogan, Cate Shortland or Alex Proyas? Or, more recently, Kriv Stenders, the director of Red Dog?

And does it matter in a modern world where the difference between TV, feature film and digital is blurred and access to better technology means a singular director is just as likely to emerge from a TAFE course or from their own low-budget short as a film school or the Screen Australia Hot Shots program?

Students “don’t have the traditional pathway as much any more,” says one film school manager.

The Sydney Film School, for instance, has earned some international success with graduation films in foreign languages made by international students.

Some argue the fragmenting of media and pathways to the screen has caused instability at an institution trying to cover all bases. One screen academic argues that change at AFTRS has been a constant recently and “that presents its own challenges”.

AFTRS chairwoman Julianne Schultz suggests it is time for AFTRS to breathe in slowly. The AFTRS council doesn’t anticipate any significant structural or philosophical changes under the incoming Peplow, she says, given he was involved in the school’s recent restructure. “And his experience in recent years in Britain and Germany has confirmed the wisdom and potential of this approach,” she says. “His analytical, creative and management skills are of the highest order.”

The question being asked is whether graduates are currently of the highest order. On the output score, the Victorian College of the Arts appears to be the school du jour despite five years of uncertainty following a merger and management upheavals (as AFTRS’ annual federal funding of about $24 million has remained stable). AFTRS is producing technicians; Melbourne’s school is producing the vision.

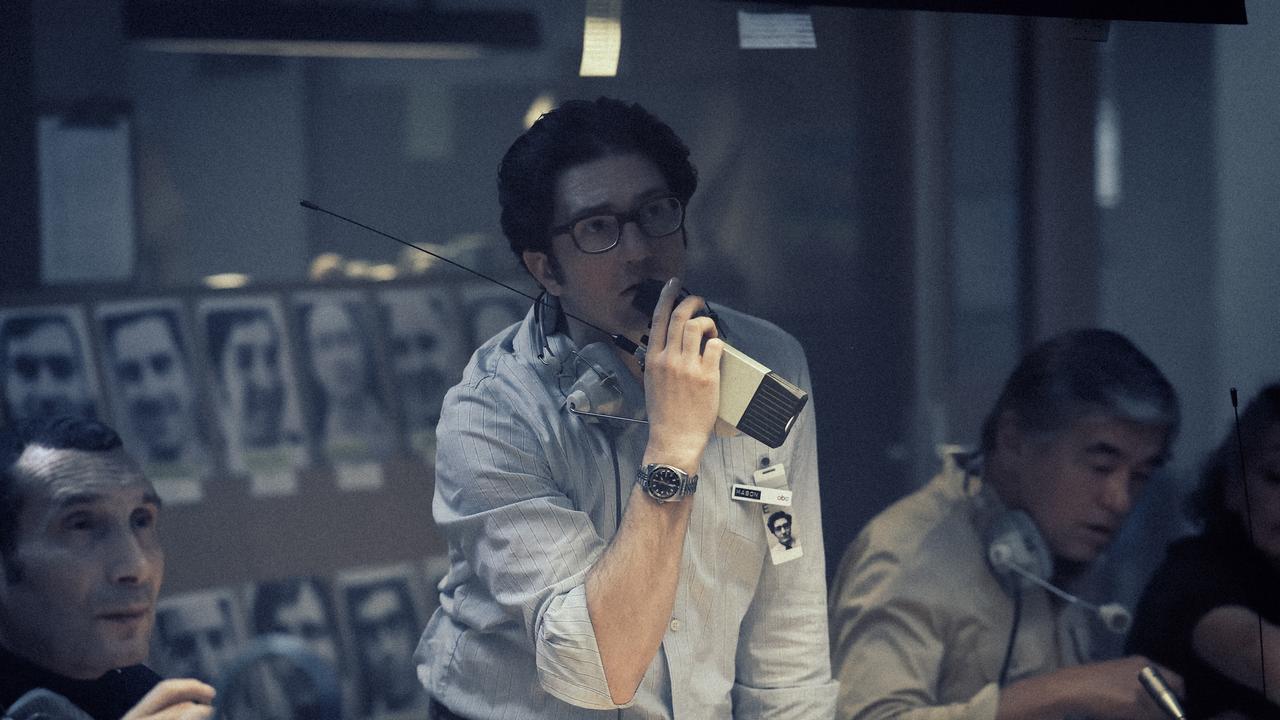

Typical but not comprehensive of the difference would be the US drama series True Detective, on which AFTRS alumnus Patrick Clair won an Emmy for designing the title sequence but VCA graduate Adam Arkapaw won an Emmy (his second) for its cinematography. Arkapaw recently completed work with another VCA graduate, Justin Kurzel, on Macbeth, his second feature, after Snowtown.

Elsewhere, VCA graduates are winning global awards and progressing into features, including Cannes award winners Ariel Kleiman, who recently released Partisan, and Glendyn Ivin (Last Ride, Gallipoli), or winning at the box office (Robert Connolly’s Paper Planes) or with critics (Infinite Man’s Hugh Sullivan).

Both schools produce many short films as graduation pieces and, given the proliferation of film festivals globally, most can claim a festival selection or even a prize from some far-flung fest, from Karlovy Vary in the Czech Republic to Rhode Island in the US.

Shorts remain a key indicator of output though and local short film festival directors admit AFTRS’ films are not demanding selection. Given the school’s status and relationships, few are willing to air their grievances publicly — though one says, fuelled by anonymity, “AFTRS should be blown up and started again.”

Paul Harris, long-time director of Australia’s largest short film showcase, the St Kilda Film Festival, wouldn’t go that far, but he says AFTRS films have been “very disappointing” historically.

Harris, who became StKFF director in 1999, describes the difference in output from the schools this way: “AFTRS has got the gear and the VCA had the ideas.”

“In the past (AFTRS films) used to be shot on 35mm with Dolby sound and starring David Wenham and Barry Otto, and technically were at a very advanced level but not films that reflected any personal insights, whereas the VCA films were like guerilla activities,” he says.

As a result, he says, “of 15 of my 18 years, there was never an AFTRS film you’d want to run on opening night. They need to be idiosyncratic and crowd-pleasers.” And those films tend to be VCA films, he says.

“I’ve always argued that if a film is technically crude but speaks to an audience, production values don’t count. Basically, today, there are so many entertainment options, if you’re going to stand out and gain attention in a cluttered media landscape, it comes back to the concept and appeal. AFTRS is like a car wash: you go in one end unformed and come out the other a polished filmmaker.”

He and others say AFTRS films have improved recently though their conceptual blandness points to another criticism of the school: that it lacks diversity and, to be blunt, its students come from a homogenous, inner-city, moneyed crowd.

In response, the school points to a growing intake of interstate and international students and its indigenous stream has been a significant achievement.

Schultz says the introduction of the BA “has broadened the base” and “students are coming from a wide range of backgrounds and locations”.

She says the AFTRS council is “aware of the costs of living in Sydney and has introduced a scholarship scheme to assist those of low SES and in need, and we are planning to expand this in coming years. The council is committed to making these courses available to the most able students irrespective of their background, it is determined to ensure that the full range of Australian stories can be told by graduates who know them both from their own experience and by being exposed to deep cultural knowledge and history through their education at AFTRS.”

Schultz and her council are fairly relaxed about the school after undergoing the changes under Levy, most particularly a relocation to the inner-Sydney site that has placed its students within Jaffa-rolling distance of key production companies such as Animal Logic and Fox’s working studio spaces.

Schultz says Levy securing of self-accreditation under the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency scheme has allowed AFTRS to create “a more comprehensive and integrated degree and non degree program”. And the council’s push for the BA screen degree arguably has sharpened the school’s focus on its former raison d’etre. “It will mean students are equipped to cope with and thrive in a very different and rapidly converging screen and broadcast world,” she says.

The role of a film school in a converged digital world is in flux. Even Canberra appears to be looking at screen policy anew without the distinctions between television and film.

Schultz believes AFTRS is “extremely well placed” to adapt. “We have studied the changing environment very carefully and distilled the skills knowledge we think our students will need: in storytelling, history of film, cultural knowledge, entrepreneurship and production skills across the whole range needed to work in these industries,” she says.

“The course includes a mix of theory and practice from day one, and becomes increasingly production orientated over the three years of the BA and then the fourth and final honours year. In the age of iPhones and YouTube we aim to educate the next generation of industry leaders and give them the skills and capacity they need to thrive in a rapidly changing world — where screens are more important than ever before.”