Another side of Bob Dylan – the dreamer

“Some of the assumptions we’ve made about him are too simple,” says director James Mangold, whose film A Complete Unknown captures the frenzied four years that saw The Bard rewrite the rules of folk music—and his own mythology.

In the opening scenes of A Complete Unknown, James Mangold’s Bob Dylan movie, a young Robert Zimmerman (Timothée Chalamet) makes his way to a New Jersey hospital, guitar in hand, to visit folk singer Woody Guthrie (Scoot McNairy), who lies pale and diminished by Huntington’s disease.

Nearby, Pete Seeger (Edward Norton) sits watchful, his eyes kind. It’s 1961 and Dylan, still hitchhiking his way into folklore, begins to play Song to Woody.

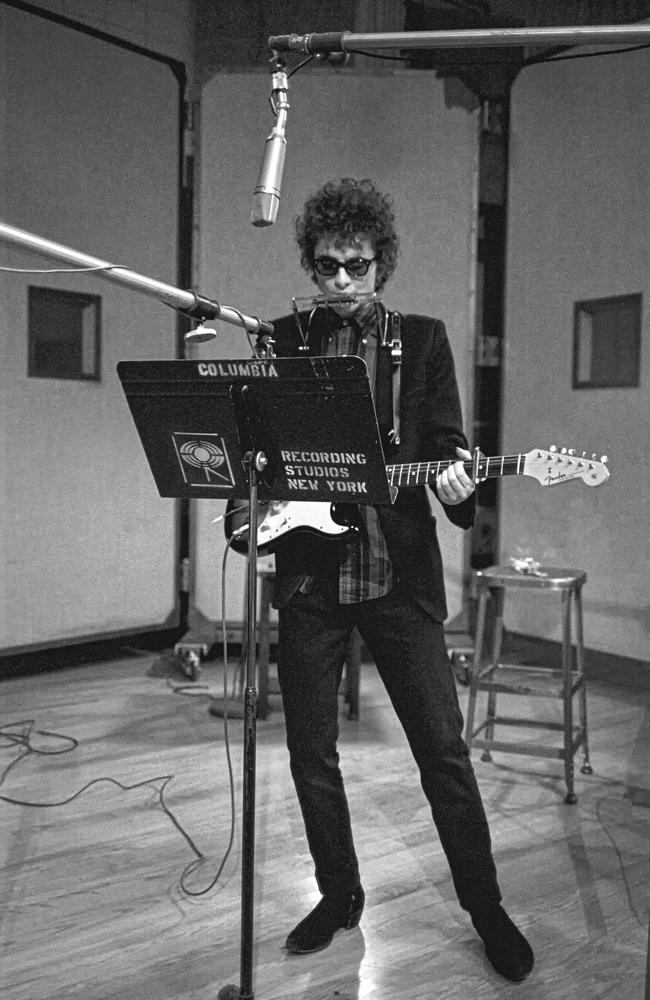

For Dylan fans who have traced his shadow in DA Pennebaker’s seminal film Don’t Look Back, which captures him raging through England’s 1965 tour like some combative prophet, or in Martin Scorsese’s two fawning Dylan films, it is a glimpse of the man before the armour. Here is no pugilist, no enigma wrapped in Wayfarers, but an earnest, awkward young man softened by awe.

It’s a side of the Nobel literature laureate few have seen and one Mangold seems determined to show.

“It was clear that Bob went on a quest. There was an optimism or dream to that quest that wasn’t cynical at all but was almost naive,” Mangold says on a Zoom call. “He was trying to live out a fairytale in a way.”

Arriving in Australian cinemas on Thursday, A Complete Unknown draws from Elijah Wald’s 2015 book Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties, and zeroes in on the frenzied four years that culminated in Dylan’s famous betrayal of the Newport Folk Festival’s purists in 1965.

Mangold, who worked closely with Dylan while developing the script, says their conversations helped dismantle the myth of the man often seen as cryptic or willingly obtuse.

“I’m not a guy who’s writing a biography, so I ask different kinds of questions,” Mangold says.

“I just felt in him that still – despite the way we all characterise him – there’s this wonderful, childlike curiosity. I didn’t feel this mysterious, enigmatic character. I’m not saying it doesn’t exist, and I’m not saying he hasn’t sometimes cultivated it. But it did give me pause, realising that some of the assumptions we’ve made about him are too simple.”

For Dylan, who has lived under an “atomic gaze” since his early 20s, this seems inevitable to Mangold. “What does it feel like to spend your whole life where anything you do, any twitch you make, is hunted?” Mangold says. “I do think there’s a part of his guardedness that’s really quite natural.”

For the film, five years in the making, the cast led by Chalamet, Norton and Monica Barbaro (who plays folk legend Joan Baez) dived into rigorous musical training to prepare for the performances, in which they played their instruments and sang live into period-accurate microphones.

Chalamet, 29, who broke out in Luca Guadagnino’s achingly romantic Call Me By Your Name and later starred in Denis Villeneuve’s Dune adaptations, learned 13 songs for the role, immersing himself in years of harmonica, dialect and movement coaching. He also made a pilgrimage to Dylan’s hometown, Hibbing, Minnesota, where he connected with a collector who lives in Dylan’s childhood home.

Among the relics he was shown was a record sleeve Dylan had sketched on: a yellow brick road leading to New York City, labelled “Bound for Glory”, alongside the first stanza of Song to Woody. To Mangold, it was a glimpse into the artist’s uncorrupted ambition: “You take an artefact like that and you see this dreamer. There’s nothing cynical about it. It’s a kind of fairytale that a young man is imagining – an escape, an ascent.”

In A Complete Unknown, Mangold wasn’t interested in telling the cradle-to-grave story of Dylan; rather, he wanted to capture a snapshot of a community and culture in flux.

“It’s about locating a segment of a human life that has a story sense to it – a beginning, a middle and an end,” he says. “Most movies we see aren’t about people from when they’re born until they die.

“It’s about a specific, turbulent, turgid, interesting time in their life that seems to have a resolution or grace or tragedy, but there’s somehow a journey. You have to conceive that my film covers Bob from the ages of 19 to 24, and in that period he wrote some of the most significant songs of the century.

“How many of us can speak of those years? Somehow his pencil and guitar pick struck a kind of gold and power that had been unheard of.”

Mangold, who directed the Oscar-winning Johnny Cash film Walk the Line, bristles at the term biopic. “The word is such a shitty phrase,” he says, tersely. “It’s a way of putting down a movie like it fits some kind of formula.”

Inspired by former mentor Milos Forman, and Forman’s Mozart epic Amadeus, Mangold sought to explore the impact of Dylan by looking at those around him: Dylan’s lover and artistic opponent Baez; pen pal Cash; and civil rights activist Suze Rotolo, Dylan’s first New York City girlfriend (renamed Sylvie Russo and played by Elle Fanning).

“In some ways I think it’s hard to penetrate Bob,” Mangold says. “The magic of that kind of talent is most interesting in the way it affects those around the person. It allows you to understand how Bob might feel, in a way, different from everyone else.

“Each of these people has a different relationship to the power that Bob has. And Bob has a relationship to it. It’s both a blessing and a curse because it separates him from everyone and makes everyone want something from him. I felt if we examined this, it might help us understand how Bob moves from an innocent into this more guarded, jaded character.”

To Mangold, Fanning’s character is the only relationship that Dylan has that isn’t transactional or competitive. The film is full of lovely scenes of the two just vegging out, eating Chinese takeaway, being slobbishly and blissfully in love. “All she wanted was love and a sense of connection and intimacy with him. She loved him before he was Bob Dylan. Every other relationship was somehow dealing with his power.”

Mangold is keenly aware of the film’s potential to introduce Dylan to a new generation. Even Chalamet admitted to knowing little about Dylan before signing on.

“I’ve had people come up to me with their 14-year-old kids and say: ‘I brought them and they loved it, and they had never heard his music once in their lives yet,’” Mangold says.

“The great thing about folk music is that it’s unadorned with production. It doesn’t sound of a period. It’s so pure. In that sense, it stays powerful.”

A Complete Unknown opens in cinemas on Thursday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout