David Bowie film Moonage Daydream to open at Melbourne International Film Festival

An ‘immersive’ documentary designed to be viewed at IMAX brings Ziggy Stardust to the next generation.

Moonage Daydream, the new documentary about David Bowie, opens with Friedrich Nietzsche’s proclamation that God is dead and humans must become gods themselves.

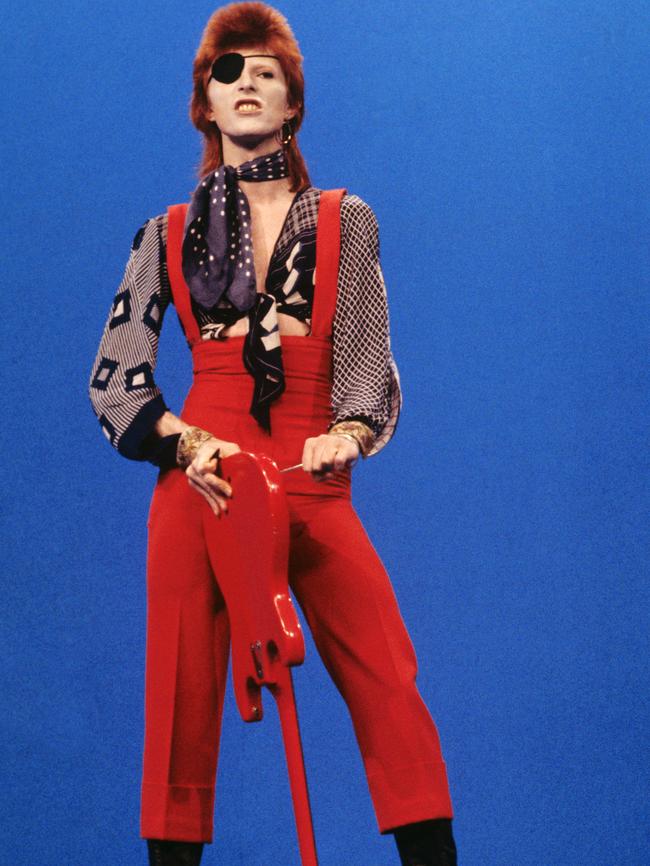

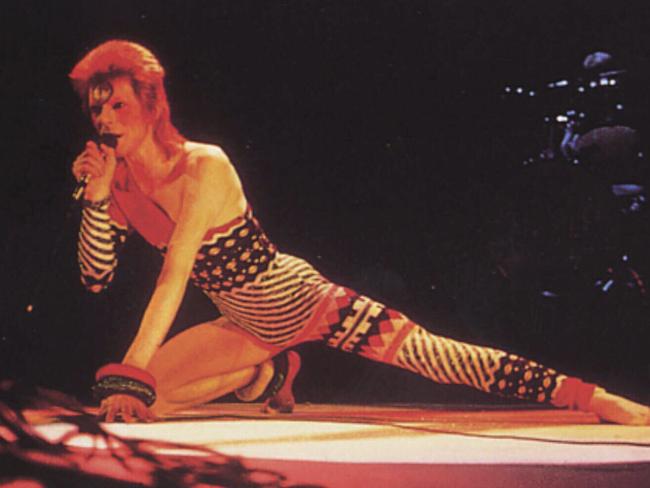

Cut to concert footage from the early 1970s when Bowie the young rock god was in his prime, with adoring fans at his feet. It’s when Bowie introduced his androgynous, space alien alter-ego Ziggy Stardust in the song Moonage Daydream, from his 1972 album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.

If Bowie had come out as Ziggy in today’s era of gender fluidity, how would he define himself and his sexuality? I ask filmmaker Brett Morgen, whose documentary Moonage Daydream – opening at the Melbourne International Film Festival next week – is the first to be authorised by Bowie’s estate.

“I don’t think he would,” Morgen replies. “I don’t think he liked labels. Bowie celebrated the individual.”

Morgen, 53, is a renowned documentary maker whose previous subjects have included Hollywood producer Robert Evans (in The Kid Stays in the Picture), the Rolling Stones (Crossfire Hurricane), and Kurt Cobain (Montage of Heck). He was 12 when Bowie first entered his life, and it was more than a musical revelation.

“I don’t know what came first, Bowie or puberty, but he was the one who told me it was OK that I was having these feelings and that I was not my parents,” he says.

“He helped me understand my own sexuality and my own disposition and I think he’s served that role for so many generations. What’s wonderful is you show this film to a young person now and they don’t see how political it was, how dangerous it was for him to go on television in 1974.”

Morgen is referring to Bowie’s appearance on The Dick Cavett Show, when Cavett questioned where Bowie came from in an introduction to the audience. “Who is he? What is he? Where did he come from? Is he a creature of a foreign power? Is he a creep? Is he dangerous? Is he smart? Is he nice to his parents, crazy, sane, man, woman, robot?”

In the ensuing interview, Cavett asked Bowie why rock stars tend to have premonitions of doom in their work and in their life. “Because they’re pretty nutty to be doing it in the first place,” Bowie responded. “Very tangled minds, very messed-up people.”

In a rare personal moment in Moonage Daydream Brixton-born Bowie (real name David Jones) credits his elder half-brother, Terry Burns, for igniting his sense of intellectual curiosity and for giving him a copy of Jack Kerouac’s novel On the Road, which influenced him greatly. Burns would later be diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. In the film Bowie speaks of developing “a strategy to avoid the pitfalls of mental illness”. His strategy was to make art and to use himself as a canvas.

Morgen’s film, designed to be viewed at IMAX and to be an immersive experience, touches on Bowie’s film work including his starring role in Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence, although it mostly follows the creation of his music. Particularly interesting is Bowie’s move to West Berlin in the late 1970s when in his stripped-down, post-spaceman era, he reinvented himself as a songwriter and developed more abstract forms of music with Brian Eno and producer Tony Visconti (also the music producer on Morgen’s film), which led to one of his best albums, Low.

At the other end of the spectrum, the film covers his 1983 period of releasing upbeat commercial songs including Modern Love on his Let’s Dance album, which remains his most successful. Bowie comments wryly about accepting the role of entertainer and scoffs at the purists who accused him of selling out.

Right up until his death in 2016, he was creating music and art. He released new albums, The Next Day in 2013 and Blackstar in 2016. He even found time to write songs and collaborate on a Broadway musical, Lazarus. A bonus of the film is that we get to see his wonderful paintings. At one point he talks with touching insecurity about having had several invitations to exhibit them and how he turned them down.

Bowie’s widely known drug use is not mentioned, though he is often seen sniffing and smoking cigarettes. Nor is his 2004 heart attack, after which he stopped touring. He’d already given up smoking, which he said was the hardest habit to kick.

“I wasn’t hiding from the drugs,” Morgen says. “The scene going into Diamond Dogs was my way of evoking his state of mind when he was in Los Angeles. He seemed like he was completely batshit f--king crazy. Do I need to show him snorting coke? I’m just trying to get into his state of mind. I thought the fragmented chaotic montages achieve that goal.”

Morgen was born in Los Angeles and still lives in the city, with his producer wife, Debra Eisenstadt and their three children. Five years ago he had a brush with death, and he says it’s what the film is about.

“I had a heart attack on January 5, 2017, about a year into working on the film,” he says. “I flatlined for three minutes and I was in a coma for a week. I had a heart attack, not because of genetics, but because my life was totally out of balance and out of control. I was a workaholic and put everything into my work. My sole sense of self worth was tied to my work. Like Kurt Cobain, I could not handle criticism in any way, shape or form. Montage of Heck felt very personal to me.

“My heart attack happened the day after my son’s eighth birthday and I was in a coma the day my daughter turned 12, which was David Bowie’s birthday, January 8. When something that dramatic happens, you start to ask these bigger questions, like what message do I leave for my children? And my message was work really hard and don’t die. I was going to work every day listening to David and I felt like he kept sharing these lines in his interviews that were basically a road map for how to live a balanced life and how to make the most of the days we have in front of us. He must have saved so many lives. He certainly saved my life through the process of making this film.”

Morgen’s only meeting with Bowie was in 2007 to discuss making what he terms “a hybrid nonfiction film”, but the timing didn’t work out. “When David passed away in 2016, I was already tracking this idea of doing an immersive project and he seemed like he would be the perfect subject.”

In 2018, Bowie’s estate granted Morgen access to material including his never-before-seen drawings, his journals, poetry and art, unreleased 35mm and 16mm footage and 40 exclusively remastered songs, including Starman, Changes, The Jean Genie, Life on Mars, All the Young Dudes, Rebel and Fame.

Of course, Bowie was a workaholic, too, though he eventually got his life in balance. After his heart attack at age 57, he became a kind of spiritual adviser and was very grounded, Morgen says.

“He was a sort of a neo-Buddhist. He never ascribed to one belief system, but if anything, he was more aligned with Buddhism.” In the film he talks about finally finding the spiritual and emotional freedom to explore a real romantic relationship with Iman, his wife for 24 years until his death.

Given Bowie’s hard living when he was young, which may have contributed to his death from liver cancer at 69, did he ever believe the adage, to quote Neil Young, “It’s better to burn out than to fade away”?

“No, no, no, I don’t think so, not at all,” Morgen says. “This is a man who loved life. I’ve never met anyone who appreciated life more than him.”

Bowie’s death came as a huge shock to his fans and to the world at large. Images of the singer in his various guises and as himself whirled across the world’s media and he was widely mourned.

Still, you won’t find anything about his death in Moonage Daydream. Morgen in fact wanted to steer away from the personal this time, so the film doesn’t mention Bowie’s first wife, Angie, or his two children, although he does include Bowie’s second wife, Iman.

“Following Montage of Heck, I felt that I had exhausted the creative possibilities of biography, and that I wanted to try to create a new form of cinema that was more experiential,” Morgen explains in Cannes where Moonage Daydream had its world premiere, to acclaim.

“With iconic artists, like the ones that I tend to work with, you can go to Wikipedia and get the A through Z of their life. But I wanted to give you everything that you can’t get there or that you can’t get from a book.

“So I came up with this idea to do the IMAX music experience, which is like a show, just having the music wash over you.”

Allowing Bowie to do all the talking in the archival material, Morgen chose not to incorporate interviews with other people giving their take on the singer-songwriter, artist, actor, writer and sometime philosopher. “I’m not interested in talking heads,” he says. “It’s a waste of screen to me – it’s too much real estate to give up just for lips moving. You can have sound that is doing one thing and image that’s doing something else and together they create a new meaning and size in cine montage with a movie camera. That’s my love. That’s what I’m interested in.”

What did he discover about Bowie that he didn’t already know?

“Everything was discovered,” he says. “I knew he was an amazing artist, but I had no idea what an amazing, inspiring human being he was. I didn’t know anything about his philosophy on life. I came into it knowing the artist and I left with a much greater appreciation for the man.”

A considerable amount of the archival material came from Australia, he notes. “The Australian archives are usually phenomenal,” he says. “In every movie I’ve done there’s just been a plethora of archival footage from Australia.”

In the film, Bowie mentions Australia as one of the places he liked to visit. He once had a residence in Sydney’s Elizabeth Bay. “It was around the time of Let’s Dance or shortly thereafter,” Morgen confirms. While some of the Moonage Daydream material comes from previous Bowie films, about 85 per cent has never been seen before, Morgen says. “All the Ziggy performances are specific to the film. I avoided using any shots that were used in the Ziggy concert, for the most part.”

Morgen says Bowie is more relevant today than ever. “Bowie’s again a cult, a prophet of mythical proportions. There’s nothing anachronistic about Bowie. When I watch the film it’s not a nostalgia trip. I feel like it’s all happening now. I can take anything he’s saying and apply it in my life today. When I hear his songs on the radio, I feel like they were recorded last week.”

In 2020 and 2021 Bowie was the most listened to deceased recording artist on vinyl. This year he was announced as the best-selling vinyl artist of the 21st century. “When he passed, he was nowhere near that, but he surpassed Michael Jackson, the Beatles and Elvis,” Morgen says. “So I think we’re coming into an era of Bowie right now.”

Moonage Daydream screens in IMAX at the Melbourne International Film Festival from August 12, with talks by Brett Morgen on August 12, 13 and 14; and in VMAX in Sydney with Morgen on August 15 and 16. Moonage Daydream is in general release from September 15.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout