Collection frames an ancient landscape

AFTER many years of negotiation, the exhibition Australia: land and landscape will open in London in September.

A PATRON of natural history, Joseph Banks was enthralled by the unknown curiosities he saw on the east coast of Australia during his scientific tour of the South Seas with Captain Cook. Long after Cook's death, Banks recommended colonisation. However, many early settlers found the coastal scrub and inland plains to be very different from the "pleasant pastures" and "mountains green" of "England's green and pleasant land", as invoked by William Blake in 1808.

Some yearned for their place of origin and returned home as soon as they could. Convict artist William Lycett, for instance, after his return to Britain and being again arrested for forging banknotes, is believed to have slit his throat rather than endure a second visit to the fatal shore. Others, often free settlers, such as John Lewin and GW Evans, flourished in their new homeland and provided some splendid watercolours of the early settlements, showing that they felt comfortable with both pastoral landscapes and the wilderness.

After many years of negotiation, Australia: land and landscape will open in London in September. The exhibition is to be displayed at the Royal Academy of Art, London's premium temporary exhibition venue, and will be the largest historical survey exhibition staged outside Australia, covering Australian art from 1880 to the present day. It is restricted to landscapes because the Australian landscape -- the land, sea, cities and sunshine -- is what pre-eminently defines our country for many people and because land or country is central to Australian indigenous art. It is an exhibition of around 200 works, some of the finest in Australian art, selected from public collections around the country and a few in Britain. Half the works are from the National Gallery of Australia.

It will present our country's land and landscape as it has been variously depicted over time. There will be observations of highly urbanised early colonial lives with growing seaports that served the inland production of early wealth for export, chiefly wool and gold, but also whaling. And there will be works that reflect the way in which settler artists began to consider the distinctive forms of individual gum trees, of bush country and tropical or temperate rainforests as well as the vast deserts that fill most of Australia, a land geologically far more ancient than Britain.

By the 1820s, landscape painting, headed by JMW Turner and John Constable, had become the dominant tradition in Britain. And, given the compelling natural scenery and distinctive light of Australia, landscape painting also soon became the central concern of Australian artists, and remained so for much of the 20th century.

The light-filled pastoral scenes of British-born John Glover, who settled in Tasmania in 1831, shifted from what was often formulaic work in Britain to more natural and unusually high-keyed Australian landscapes. When he incorporated Aboriginal figures into his work, this farmer-artist revealed his sympathy for the hunter-gatherer Aboriginal people who had preceded his family in caring for the land. His paintings and, later, those by the Austrian-born Eugene von Guerard, also occasionally expressed guilt for taking the land from the previous indigenous owners.

In the later 19th century, the artists begin to dramatise the intense light, burning heat and dryness of many an Australian summer, using a characteristic blue-and-gold palette as well as the gently subdued tones of early morning and evening. It was a time when some of Australia's best known and most loved artists, Tom Roberts, Frederick McCubbin, Arthur Streeton and Charles Conder, came into prominence and when artists began to talk about an Australian tradition and a specifically Australian art. By this time, Australia had a number of Australian-born artists. They created a new vision of urban Australia, the bustle of modern city life populated with fashionably dressed people as well as landscapes in which men, women and children lived and leisured in harmony with their environment.

After Federation in 1901, artists used strong emblems in their landscapes, particularly the sturdy monumental eucalypt, redolent of masculine power. They also depicted the city, suggestive of progress; and, after 1910, the beach again became indicative of Australian egalitarianism and a healthy lifestyle.

The 1920s and 30s were a time when women artists came to the forefront, developing distinctive modernist approaches to their local environment. The construction of the massive Sydney Harbour Bridge from the mid-20s became a symbol of hope for many as well as a sign of Sydney's progress and modernity. It was a favourite subject of artists such as Grace Cossington Smith and Jessie Traill, who were attracted by the bridge's modernist forms.

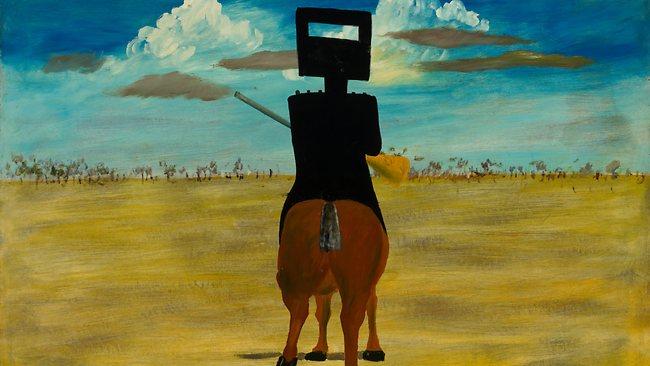

The 40s were a dynamic and creative decade for Australian art. World War II, isolation and the threat of invasion galvanised younger artists to express themselves with a new force, and their art took on a more personal, haunting expressiveness. The artist, and later Royal Academician, Sidney Nolan became one of the most imaginative and compelling painters of the Australian landscape. In a 1948 edition of The Australian Artist, he said of his 1946 iconic Ned Kelly series that it was "a story arising out of the bush and ending in the bush" and "the desire to paint the landscape involves a wish to hear more of the stories that take place in the landscape".

Russell Drysdale turned away from Australia's fertile coastal regions to the less productive inland country and told stories of stoic women firmly located in the landscape. He showed Australia as a place loaded with strangeness, and in some works he depicted the dried-up earth where only flightless emus remained.

During the past 50 years, although no longer a dominant subject, landscape has remained a recurring theme for painters, printmakers and photographers. A number of the artists have been particularly conscious that the land here in Australia, and our way of viewing it, is markedly different from that elsewhere.

Fred Williams created a highly original way of viewing the Australian countryside. He made a virtue of flatness, sparseness and super-subtle tints in his delicate but weighty landscapes. He explored different formats for viewing the land, to convey the unbounded, timeless country in which a European perspective becomes irrelevant.

The Australian sun, its blazing force and its seductiveness, has been an important motive in Australian art. In his Sydney Sun, John Olsen painted a joyous celebration of the sun cradling the surrounding landscape, "like a benevolent bath, bubbling and effervescent" (as Olsen said in a letter in 2000, recalling his intentions at the time of painting it). Howard Taylor observed in a 1984 interview that in Australia "the sun is straight above you, it tends to flatten things out. You miss that half-covered sky or the diffused light that you get in Europe."

Bryan Robertson, director of the Whitechapel Art Gallery, when he presented Recent Australian Painting in London in 1961, observed in an article in The London Magazine that Australian painters "know the geology of the land and the names of plants and trees and the histories of particular regions in a way that European artists do not". Certainly, from the beginning, explorers and artists have been concerned with the unique plant forms of Australia. Some present-day artists have refreshed old botanical observations. Fiona Hall, for instance, has done so in Paradisus Terrestris 1989-90, a suite of 23 miniature aluminium sculptures of plants, both Australian and exotic, paired with human sexual organs.

Much Aboriginal art is about the land, made of materials gathered from the land, etched into its surfaces as rock engravings or ceremonial ground designs and painted on to bodies. The people's relationship to the land, depicted in a visually rich language that varies considerably across the continent, is often embodied in the iconography of "the Dreaming" or Creation narratives. The imagery can be traced back some 50,000 years and constitutes the world's oldest unbroken art tradition. Painting in natural pigments on flattened sheets of eucalyptus bark is the archetypal art form in Arnhem Land and the surrounding regions and, until the 70s, was regarded as the only traditional form of Aboriginal painting. The great revolution in modern Aboriginal art had its origins in the Western Desert, in the government settlement of Papunya. The catalyst for change came in the form of non-Aboriginal outsider Geoffrey Bardon, who invited the senior men of the community to paint a series of murals on the school walls in the Western Desert style. The men went on to produce paintings on portable supports in acrylic as well as natural ochres, creating works that are appreciated for their mystery and their beauty.

Aboriginal desert painting is today a significant component of Australian national pride, partly for the extreme antiquity and aesthetic beauty of its traditional forms, each community with its own inflections of an ancient iconography. In the mid-1900s, the first generation of urban-based indigenous artists emerged, whose art is often provocative and political in nature, as well as witty, and uses many different media.

These are just some of the many aspects of the rich Australian landscape tradition that will be displayed at the Royal Academy later this year. It will demonstrate that Australia's artists are at least as inspired as our actors, filmmakers and writers -- and that Australia is as much a cultural nation as a sporting nation. It will also show that our visual arts tradition has a longer and more venerable history than our sporting tradition.

Anna Gray is the head of Australian art at the National Gallery of Australia. This is an edited extract from a piece to run in the National Gallery of Australia's Artonview No 74.