Clarice Beckett show at Art Gallery of SA to offer new view of artist

The exhibition organised around the times of day Beckett painted will also highlight her interest in spirituality.

Last month, art curator Tracey Lock and former gallery owner Rosalind Hollinrake made a tour of Melbourne’s bayside suburbs to view the spots where, some 90 years earlier, Clarice Beckett had stopped to paint.

They visited St Kilda and Luna Park, where Beckett painted a windswept scene of a woman in hat and coat crossing the road, the supports of the Scenic Railway behind her. From there they went to Beaumaris to see where the Beckett family home once stood, and to walk along the headland where Beckett pushed her trolley and set out her paints and canvas boards.

“It was fantastic for me to get a sense of the proximity of her home and the coastal fringe, and to get a sense of the rise and fall of the ground,” says Lock. “You can see the little sandy paths through the sheoaks and tea trees and acacias. You get a sense of what it would have been like for her every day, wheeling her cart through the bushland and down to the foreshore.”

Lock, curator of Australian art at the Art Gallery of South Australia, made the visit to Beckett’s Beaumaris as she prepares to open a major exhibition of Beckett’s work. The Present Moment, due to open later this month, is a survey of Beckett’s brief career, where the paintings will be organised according to the time of day Beckett made them.

Beckett often would rise at 4am to start painting. She wanted to capture the particular atmosphere of “the moment of dawn, the first breath of light”, as Lock puts it. Seeing where she painted has helped Lock locate Beckett’s paintings within space and time.

And Beckett’s paintings are unlike anyone else’s. Beaumaris and neighbouring Mentone are well-known subjects in Australian art. Streeton, Roberts, McCubbin and Conder all painted there.

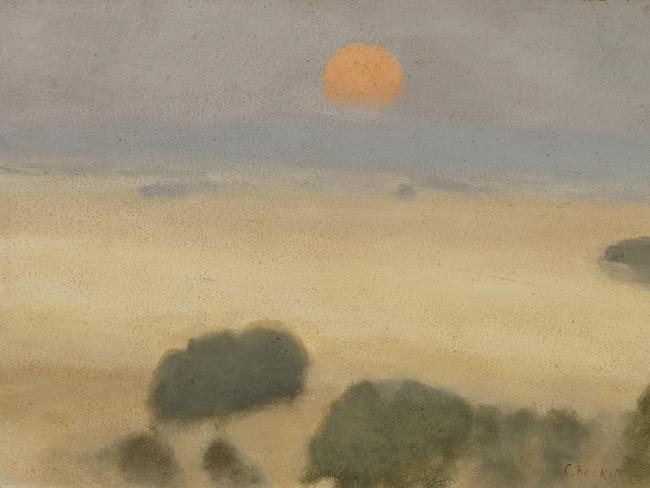

But compare the work of the Australian Impressionists — busy with detail, blazing with blue and gold — and Beckett’s rendering of the same landscape.

Her paintings are quiet and still, the forms almost dissolving, or in the process of becoming.

“She was standing on the same beaches, looking in the same direction,” Lock says of Beckett and the artists who worked there 40 years earlier. “She was responding to the atmospheric effects — the light, the reflection, the luminosity. But her approach is a way of painting that eliminates detail. She had a limited range of colours on her palette, so everything was simplified. The details aren’t there that you see in the Australian Impressionist works, but the atmosphere is there, the accuracy and truthfulness.”

That Beckett’s work should be better known in Australian art has been Hollinrake’s mission for a half-century and is one Lock shares.

Hollinrake had been intrigued, in the 1960s, by two paintings she had seen in a private collection, one of which was signed C. Beckett. At the time she was married to Barry Humphries and through their circle of friends — who included Sidney Nolan and the Boyds — she attempted to find out more about this mysterious artist. No one knew.

The moment of revelation came when Hollinrake was at her gallery in Melbourne’s Armadale and a woman came through the door with a bundle of paintings, and asked: “Would you be interested in these?”

The woman was Beckett’s sister, Hilda, and in addition to the pictures she’d brought under her arm, there was a whole stack of them at a farm near Benalla in northern Victoria.

The story of Beckett’s rediscovery is no less remarkable for being retold.

“Within 24 hours they were in a car, heading out to the family farm,” Lock says. “That’s where they came across the works, in this open-sided shed — about 2000 canvases.

“From there, Ros and Hilda worked together to conserve the works. Ros rescued what she could, and staged an exhibition in 1971.”

Patrick McCaughey, future director of the National Gallery of Victoria, reviewed the show for The Age under the headline “Remarkable modernist”. Fred Williams thought Beckett ahead of her time. James Mollison, foundation director of the National Gallery of Australia, bought eight paintings for the nascent national collection.

Subsequent exhibitions helped establish Beckett’s posthumous reputation. Today her paintings are held in major public collections as well as by private owners, including Russell Crowe and Kerry Stokes, who have loaned works to the AGSA exhibition.

Still, Lock says, Beckett remains under-recognised by the gallery-going public and perhaps misunderstood. Her work sits outside the more familiar currents of Australian modernism as it was defined by Nolan, Boyd and Albert Tucker, and is utterly unlike the output of other female artists who were her contemporaries, Grace Cossington Smith and Margaret Preston.

“The tripwire with Beckett has been that her work looks realistic and conservative, but the experience of it is abstract,” Lock says. “There’s been a lot of work on decentring modernism, and understanding that there are multiple variants of modernism across the world … We are finally getting the words to understand what’s going on here.”

Several misunderstandings persist about Beckett and some aspects of her work require explanation. While her painting career was short — just 16 years — her work was not unknown in her lifetime and she had 10 solo exhibitions.

One of her works was shown in New York and favourably noticed. And, while the time available for her artistic practice was curtailed by her having to care for her parents, that was only in the last couple of years of her life. Beckett died in 1935 at age 48, when she contracted pneumonia after painting outdoors at Beaumaris in a storm.

Beckett had trained with Max Meldrum, who had developed his own theories of tonal painting and was regarded as something of a crank by the artistic establishment; Beckett would suffer criticism by association. But, while she painted in the “misty” or soft-focus style of tonalism, she adapted the technique and pushed it towards abstraction or minimalism.

Lock argues that while the subjects of Beckett’s work were particular and local, her intellectual preoccupations were international. Beckett was involved in Theosophy, the esoteric movement that was influential at the turn of the 20th century. She never joined the Theosophical Society but was friendly with other adherents and was very interested in The Voice of the Silence, a book by Theosophy’s founder, Helena Blavatsky.

Theosophy, which drew on Eastern religious traditions and philosophy, encouraged followers to seek spiritual knowledge beyond sensory experience. Kandinsky and Mondrian were among the artists attracted to the movement. Another was the astonishing Swedish artist Hilma af Klint, the subject of a major exhibition at the Art Gallery of NSW in June.

Lock says Theosophy taught a greater sensitivity to one’s surroundings — to be receptive to colour, movement and sounds — and this can be seen in Beckett’s paintings. They often seem to be recording a moment of contemplation, whether the subject is a St Kilda street with trams and car headlights seen through the mist, or the bright colours of parasols, swimming costumes and bathing boxes at Brighton.

“What she was reading was awakening her to this heightened state of being — that’s where the (Theosophy) literature was very influential,” Lock says. “You feel that when you look at her paintings. They are so still and quiet, she stops you in your tracks.”

The title of Lock’s exhibition, The Present Moment, alludes to this sense of quietude and stillness. It comprises more than 120 paintings. Lock decided against hanging them in the conventional way of a retrospective; that is, by starting at the beginning of the artist’s career and continuing to the end. While Beckett’s career was short, her output was remarkably consistent in quality, and different periods of her development are not so obvious.

Instead, the exhibition proceeds from landscapes painted at daybreak through to afternoon and evening. Lock says she hopes the visitor will experience the “journey of the day” as Beckett observed it.

A feature of the exhibition design is a space that suggests a kitchen. It was there that Beckett finished her paintings and planned her exhibitions — her father having denied the artist a studio of her own.

“It’s a familiar story for many women artists, they have to improvise and use shared spaces,” Lock says. Among the pictures shown in the “kitchen” is a sunset that Beckett painted on the back of a cornflakes box.

In 2019, a donation to the AGSA from Alastair Hunter made possible the acquisition of 21 Beckett paintings from Hollinrake’s collection. Hollinrake wanted her collection to be kept intact and to go into a public gallery. These works — including The Red Sunshade, Pavlova, divertissement and Evening, After Whistler — now form the nucleus of the exhibition.

Beckett’s small, quiet and unassuming works can strike people with the force of revelation — not with the in-your-face heroics of modernism, but as a subtle adjustment of one’s world view.

Clarice Beckett: The Present Moment is at the Art Gallery of South Australia, February 27-May 16.