Cape York late bloomer crossed gender divide to show home is where her art is

Relive the magic created by acclaimed indigenous artist Mavis Ngallametta.

Mavis Ngallametta’s journey began in 1944, when she was born near the Kendall River in west Cape York Peninsula. She lived a traditional life in the bush until she was around five, when her family moved to the Presbyterian Mission at Aurukun. As in most indigenous missionary and government settlements in Australia, children were removed from their families and raised within the dormitory system. In Aurukun, the remote nature of the community together with the strength of local cultures and languages meant that traditional practices were largely maintained, despite the assimilative goals of the system.

As an adult, Ngallametta was renowned as a master weaver in the styles practised in Aurukun — both the traditional methods of making string bags and the ornate techniques introduced by the missionaries. But she came to painting late in life, not picking up a paintbrush until the age of 64.

Ngallametta began painting in 2008, shortly after the senior male Wik and Kugu artists began painting on canvas. With the community’s rich heritage in ceremonial figure carving, the Wik and Kugu Art Centre had been a stronghold of men’s art and activity. In many Aboriginal art centres, there is a clear gender division, and sometimes this excludes entire sections of the community. At Aurukun, the art most coveted was the men’s sculptural work.

In 2008, centre manager Guy Allain sought to change this dynamic by inviting his partner, Gina Allain, to run painting workshops for the women of Aurukun. From the first workshop, there was a strong uptake among the women who wanted to tell their stories on canvas.

The women artists of Aurukun painted almost exclusively with acrylics. Ochres were associated with the men and customary practices — the bold white dots over red ochre of the Apelech clan; the bold black-white-red-white-black bands of the Winchanam clan; and the alternating red ochre and white clay bands of the Kugu. All of these now iconic designs were nowhere to be found in the women’s paintings.

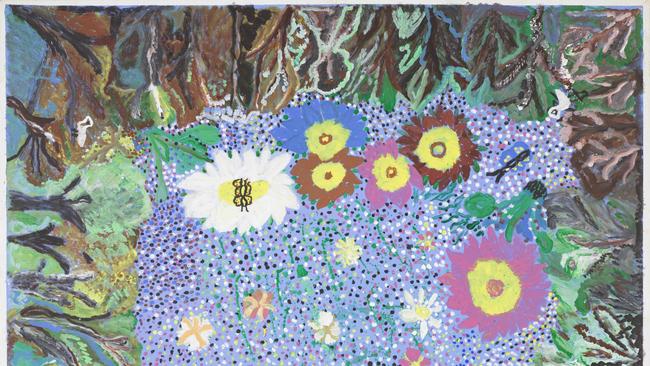

The women depicted the community’s riotous scenes of post-wet season abundance, a climatic phenomenon well known to people who live their lives just feet above the swamp line. Many of Ngallametta’s early works were likewise bold and celebratory — swamps with brightly coloured waterlilies, people collecting flowers, and families fishing and camping at their favourite spots.

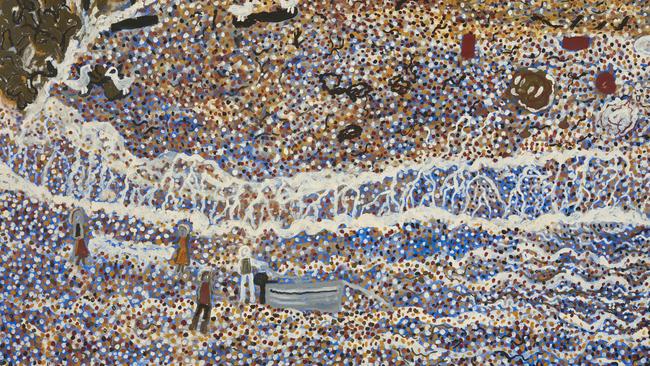

In these early works, Ngallametta drew together a number of different styles and perspectives. She painted swamps and waterlilies from above with the waterlilies in the centre, while towards the edges of the canvas stands of paperbark trees crowd around, almost falling over into the water, recalling the work of Australian landscape painter William Robinson. An important painting from this period, Wutan (2011), portrays Ngallametta with her family, including her adopted son Edgar, a traditional owner of Wutan, fishing at this inlet on the coast of the west Cape. Behind them stands a small shack while creeks and hills recede into the background beyond the trees.

When Ngallametta painted, she often used a unique perspective. Neither the flat, feet-on-ground perspective traditionally used in landscape painting nor the bird’s-eye view most often associated with Aboriginal painting, her perspective would be best described as a view at an angle of roughly 45 degrees, almost as if looking out from a coast-hugging, low-flying aircraft.

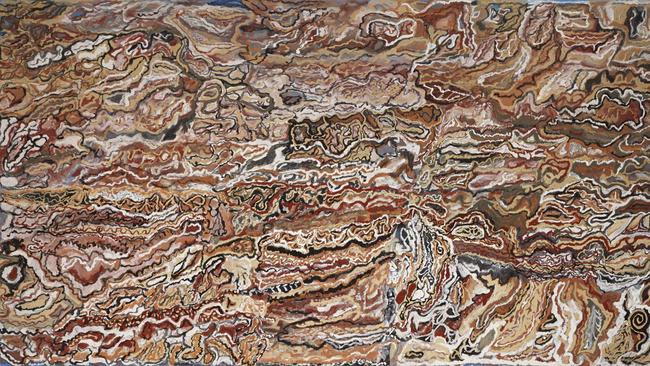

This view, when combined with varying degrees of abstraction, enabled Ngallametta over the next seven years to unify macro and micro worlds that she knew from her and her family’s country.

In order to expand her development, Gina Allain suggested that Ngallametta experiment with ochre. Natural pigments — the ochre, clay and charcoal from her country — became central components of her paintings.

It is important to note that Ngallametta’s works were extremely labour-intensive; in the studio, other women who painted with acrylics would finish a work before she had even collected her raw materials, let alone processed them or begun to paint. Ngallametta painstakingly constructed her paintings to ensure that culturally, spiritually and physically the works contained the essence of the places they depicted.

Ngallametta continued to create small-scale paintings until 2011, when she met Sydney gallerist Martin Browne at the Cairns Indigenous Art Fair. Browne thought her work showed great promise but suggested she try painting on a larger scale. Ngallametta, who had already begun progressively scaling up her works in the preceding months, adapted to the challenge quickly and was soon painting canvases measuring two by three metres. These canvases allowed opportunities for much richer storytelling — the mapping of people, places and histories — than the smaller paintings she had been making up to this point. Not a prolific creator, Ngallametta completed only a few dozen major works in the short time she was a painter. Each work would take many weeks to complete as she carefully worked away at small sections of the canvas, all the while sitting on her blue camp mattress on top of the blue acrylic base to keep the surface of her paintings pristine.

Her weaving experience was central to her compositions. Just as a weaver envisions the final form of their work and, with every action, works towards it, Ngallametta pictured the final form of her canvases, working towards it carefully, one gesture at a time.

“I am always thinking about painting,” she said, “maybe from a dream or a memory of where I have been.”

In her paintings, there are countless interconnecting white lines that entangle the elements of the composition. Representing the paths and waterways that wind through country, they appear as a sort of weaving, binding the physical, cultural and mnemonic elements of the artist’s life and work together.

Perhaps Ngallametta’s most striking group of works is her Pamp (swamp) series. Her vision of swamps can be perplexing to those who have not witnessed the tropical wetlands after a flood, and who may associate swamps with stagnant water, algae and putrid mud.

In contrast, Ngallametta’s swamps are picturesque lagoons that ring the community of Aurukun in the post-wet season — crystal-clear fresh water abounds, tainted only by the subtle tea-coloured tannins of the melaleuca trees lining the banks.

Small fish and turtles swim among the grasses, while waterlilies feature in large clusters at the centre of the swamp, and delicate smaller blooms shoot from the fringes. Ngallametta’s paintings are about place — the stories she knew, the memories she treasured and the people she loved. Each painting is about her home, and in her painting, she found a new home — somewhere she could go to remember, relive and record places, memories and loved ones.

She was an extraordinary woman. She possessed special qualities that endeared her to many during her relatively short career. Being in the twilight of life and coming from a tiny community, art provided Ngallametta with a second life, one she was determined to live to the fullest. It allowed her to travel widely, and whenever she left her community she embraced the opportunity with zeal.

She was the life of the party, often taking over the microphone at exhibition openings to tell stories of her home or to break out in song. For all of her love of travel, Ngallametta longed to return to the west Cape — to her country, her community, her family, her home. When she sang, most often it was the song that was dearest to her heart: “Show me the way to go home.”

Bruce Johnson McLean is assistant director, indigenous engagement, at the National Gallery of Australia. He is the former curator of Indigenous Australian Art at QAGOMA and curator of Mavis Ngallametta: Show Me the Way to Go Home, which is at the Queensland Art Gallery until August 2. This is an edited extract from his catalogue essay.