You wouldn’t read about it ... but now you can

Our chief literary critic picks the hidden gems of 2020 — you read it here first.

It may not have faced the same industry-wide apocalypse as film, but 2020 hit publishing hard. Most houses hit pause on the printers before mid-year, effectively placing many major titles on ice. With bookshops closed and book launches nixed — not even writers’ festivals ongoing, at least in the flesh — the fear was that even healthy online sales would not take up the slack.

Once the situation stabilised, however, those same publishers set their publication schedules back in motion with a vengeance. And so it was that September and October of this year, already a traditional high point of the calendar for releasing big books (hopefully giving them time for positive reviews and word of mouth to build hype in the Christmas lead-up) was supercharged.

Publicists, reviewers and booksellers leapt into this jammed publication period with all the dexterous industry of lumberjacks logrolling on a thawing river — shelf (and column) space had to be found for the new offerings from Craig Silvey and Richard Flanagan and Trent Dalton, after all — even as storerooms overflowed with boxes of Barack Obama’s memoir (three million copies printed in November alone).

But it was inevitable that quieter books and titles with less obvious star power attached would get lost in the mix this year. Those eccentric, left-field or slow-burning stories that so often supplant big-name titles to become readers’ favourites, given enough time and attention, had even less sunshine in which to grow in 2020.

Conscious of this discrepancy of consideration, I’ve assembled a list of those special books whose qualities may have been overlooked this year: titles weird and wonderful, recondite and witty, including superior works of genre and minor classics of contemporary lit.

It takes nothing away from marquee titles to celebrate these works: a healthy publishing industry needs both kinds of books to succeed. And readers? They deserve regular infusions of unexpected pleasure. It is good to learn that Amazon’s algorithm doesn’t know you that well, after all.

The Labyrinth (Text)

First off the boat is my novel of the year, antipodean division: Amanda Lohrey’s The Labyrinth. Lohrey suffers from having never written the same book twice — the Tasmanian author’s intelligence is too sharp and restless for that — though each of her eight fictions to date has been perfect of its kind.

This latest explores the period during which an older woman, the mother of an artist jailed for an act of violence as savage as it is inexplicable, moves to an Australian seaside town to be close to his place of incarceration. We follow the narrator as she negotiates a modest place for herself in the community, visits her damaged, dangerous adult son, and sets out to build a labyrinth in her sandy, coastal garden with the assistance of a master stonemason who is also an illegal immigrant.

Lohrey’s narrative pace is slow and steady as watching a building go up; her prose is clean and precise, as though the correct use of language was itself a moral act.

And the questions her story raises — regarding the nature of madness, how relationships between mothers and children can buckle and re-form, the ways in which we might realise sacredness in a secular world — are asked with subtlety and a purpose that, tantalisingly, lie just outside the story’s frame.

A wise book, beautifully told, by a proper grown-up.

Shirley Hazzard’s Collected Stories (Hachette)

Waspish, clear-eyed, unashamedly high-minded and often mordantly funny: Shirley Hazzard’s Collected Stories are a reminder that her later novels, justly celebrated as they are, were the second act of an already remarkable career.

It had been years since I’d encountered Hazzard’s early, “European” stories, but the worlds they summoned — filled with characters whose capacity for sadness and misunderstanding both ennobled them and rendered them absurdly, foolishly human — read as though the paint were still wet on the canvas. I’d also forgotten their epigrammatic verve. My pencil underlined more passages than it left untouched.

Editor Brigitta Olubus should be commended for the work she has done to gather these stories up, especially so for including a clutch of unknown or uncollected pieces.

My only regret: The Evening of the Holiday, which first appeared as a long short story in the New Yorker but later published as a stand-alone novella, wasn’t included as well.

Listening to the Wind (Milkweed Editions)

Tim Robinson’s Listening to the Wind was reissued late in 2019, but I’ve included it here because Robinson, a cartographer and writer who holds near-legendary status in Ireland, died from COVID-related illness this year. Robinson was born in England but moved to the Aran Islands in 1972.

There he produced a two-volume study of Ireland’s austerely beautiful offshore isles that was so attentive to place — encompassing history, myth, ecology and landscape — beautifully written and exquisitely produced, that they came to constitute a new genre: not geography, but geophany, “the showing forth of the Earth”.

Later, Robinson moved to Connemara in County Galway, the northernmost region of Ireland, and its most traditional, and there embarked on the works that became the Connemara Trilogy, which Robert Macfarlane called “one of the most remarkable nonfiction projects undertaken in English”. Listening to the Wind is the first volume of that trilogy. Every human who cares for place should read it.

Burning the Books (Harvard University Press)

The most urgent work of history I read this year was written by a librarian: Richard Ovenden, director of the Bodleian in Oxford, one of our great storehouses of printed knowledge. In his Burning the Books, Ovenden explores the deliberate destruction of books from ancient Alexandria to present-day Sarajevo, and discovers there is more at work than a blind desire to obliterate.

Libraries and archives are targeted, the author claims, because they are repositories of documents that preserve claims for human freedom and dignity. They furnish a record of the rich and inimitable value of various communities, even and especially when those communities come under threat. Attacks on libraries are preliminary sallies against abstract rights and flesh-and-blood groups, suggests Ovenden. Which makes librarians and archivists some of the unsung heroes of history.

Fathoms (Scribe)

Rebecca Giggs is a not a nature writer so much as an everything writer: the universe is her bailiwick (and if you think I’m exaggerating, google her recent essays on the joys of artificial lawn, or snail-keeping in a pandemic, or salmon on drugs). Fathoms is the result of years of research and contemplation: a cultural, historical and ecological exploration of whales and their place in human life and thought. The book is finely balanced between careful empiricism and metaphysical speculation; a prose-poem, but one punctilious in its marshalling of data. Take Giggs’s chapter on whale-fall, which describes the final descent of a dead whale, its gradual deliquescence and incorporation into the broader ocean ecosystem. It is simply one of the most miraculous and illuminating accounts of animality I’ve come across. Read it, read the whole magnificent tome: you’ll leave it filled with renewed awe for cetacean existence.

The Details (Scribner)

If Giggs reads the world like a book, Tegan Bennett Daylight reads books like they contain the world: which, of course, they do. The Details brings together essays by the Australian author and writing teacher, painstakingly crafted across several of years — each of them, after their quiet, modest fashion, a showstopper.

Daylight writes with equal grace and alacrity about the joys of Edwardian fiction and the sad mechanic exercise of grieving for her dying mother. She explores the challenges of inculcating a love of literature in young people who have never been exposed to writing beyond Harry Potter.

She writes with unblinking honesty about women’s bodies after childbirth — the stigma and silence that settles over them — and with crisp acerbity about the rewards of re-reading Jane Austen.

Like the best essayists, nothing is uninteresting to Daylight, nothing undeserving of her creative attentions. The result is uniformly superb.

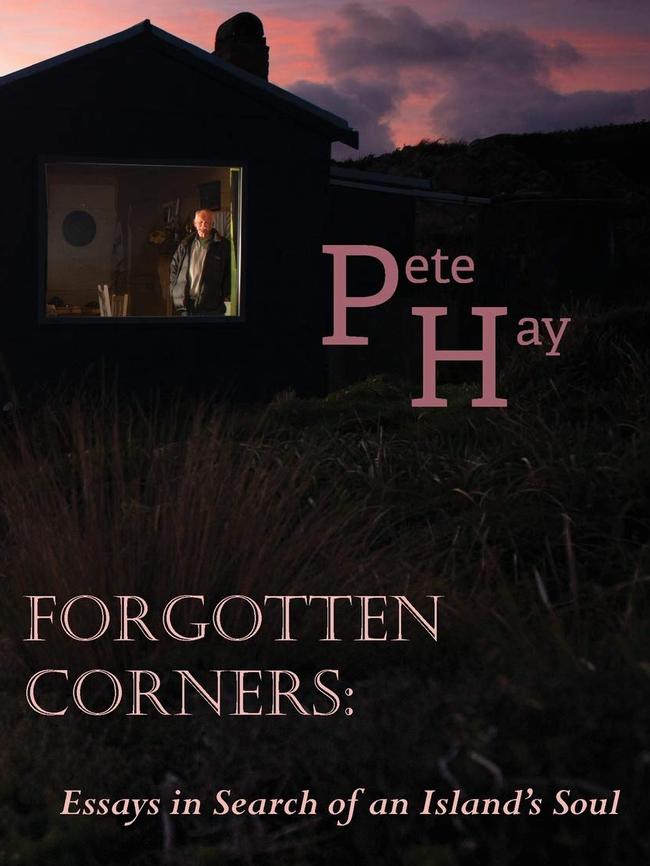

Forgotten Corners: Essays in Search of an Island’s Soul (Walleah Press)

Even as I type these words, word comes that Pete Hay’s Forgotten Corners: Essays in Search of an Island’s Soul has won the Small Press Networks Book of the Year Award. I had the honour and delight of launching this book in the lovely old stone precinct that is Hobart’s Salamanca: a fitting venue for a work so centrally concerned with Tasmanian experience.

Hay is a poet, scholar and essayist, and a true Vandemonian. His writing preserves a sense of that wildness and island isolation unique to Tasmania.

He writes with furious tenderness about his home state, and in such a way that the mainland might as well not exist.

And this is perhaps the reason why the man Richard Flanagan and James Boyce regard as the secret king of Tasmanian literature is not better known. He is like one of those exquisite Tassie pinot noirs that doesn’t travel.

You have to drink his work in situ. Hay’s sense of history and place is informed by deep knowledge and simple joy, but his essays can also be fuelled by righteous anger regarding threats to what remains of the island’s wilderness and older human folkways: so much so, I feel almost guilty letting you know of this book’s existence.

Capitalism, Alone (Harvard University Press)

Finally, an unlikely title for a literary critic to praise.

This is a revelatory account, by one of the globe’s leading economists and theorists of inequality, Branko Milanovic, of how our world works now.

His thesis is obvious, nonetheless startling in its implications: for the first time in human history, capitalism is the sole socio-economic system in the world.

But it is the way Milanovic slices and dices the existing versions of capitalism that intrigues: liberal capitalism in the West, political capitalism in China and other authoritarian states.

Democracy is the difference, and an important one, Brankovic argues — though even in the liberal West inequality is degrading democracy’s ability to ameliorate capitalism’s worst excesses.

Brankovic makes some provocative arguments along the way: abolition of the welfare state, for starters, as well as guest programs rather than full citizenship for poorer workers from the global south.

Controversial they may be, but what Brankovic wants to do is stop meritocratic capitalism going the way of its authoritarian twin.

Credibly and urgently argued, Capitalism, Alone provides a set of taxonomic tools to explain the mess we’ve gotten into. It also explains why democracy is not just a nice add-on but an intrinsic part of a just social order.

Geordie Williamson is chief literary critic of The Australian.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout