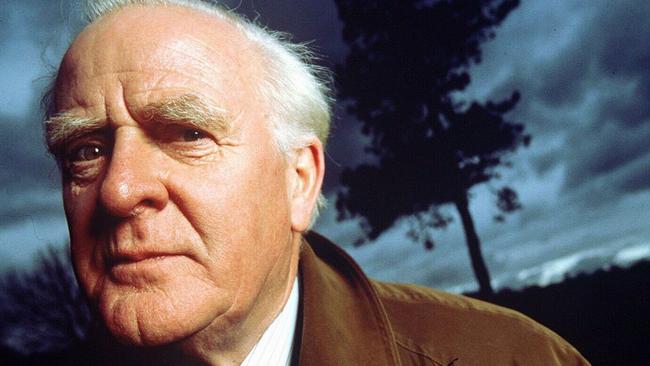

World mourns literary giant John le Carre: ‘we’ll never see his like again’

British spy novelist John le Carre has died, aged 89.

That he has been outlived by his most famous character, the rotund, balding, shabbily dressed and bespectacled master spy George Smiley, would have come as no surprise to John le Carre.

“George, you won,’’ Smiley is told by his right-hand-man Peter Guillam in the 1979 novel Smiley’s People. Smiley replies, “Did I? Yes. Yes, well I suppose I did.’’

Le Carre, who died of pneumonia aged 89, brought Smiley into the world in his first novel, Call for the Dead, published in 1961. At the time, the author was a spy himself, working for MI6, so he could not publish under his own name, David Cornwell.

He adopted the pen name that would make him famous. Le Carre means “the square” in French, and while the author, who started in British military intelligence because of his fluent German and French, said he could not remember why he chose the name, observers have linked it to his conman father, Ronnie, who is fictionalised in some of the novels.

The third Smiley book, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, about moral failings on both sides of the Cold War, was a best-seller and saw Cornwell, who had been outed as the author, leave MI6 and become a full-time writer.

Le Carre’s commitment to storytelling is best summed up in his own words: “The cat sat on the mat is not a story. The cat sat on the dog’s mat is a story.’’

He created Smiley, head of the fictionalised intelligence organisation The Circus’, as an anti-James Bond. He saw Ian Fleming's martini-drinking, womanising secret agent, who first appeared in the 1952 novel Casino Royale, as inauthentic. In the real world, espionage was less glamorous, though still cold, hard and brutal.

“I felt I had to suppress my humanity,” he said in a 2017 interview about his own days undercover. “The lies straight into the face, the befriending, the false befriending. I suppose I’ve been a lot of people in my 85 years, not all of them very nice people.”

Smiley, best remembered as Alec Guinness in the 1979 BBC TV series, survived through intelligence and cunning. While the British agent Alec Leamas (Richard Burton in the 1965 film) is shot dead in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, his handler Smiley walks away untouched. He’s still going, aged in his 90s and living in Germany, in Le Carre’s 2017 novel A Legacy of Spies, which is a prequel and sequel to The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.

Le Carre’s death was announced by his literary agent Jonny Geller of the Curtis Brown Group, who had worked with the author for the past 15 years.

“We have lost a great figure of English literature, a man of great wit, kindness, humour and intelligence. I have lost a friend, a mentor and an inspiration.’’

Geller said le Carre, who wrote 25 novels, several of which were adapted into films and TV series, was an “undisputed giant of English literature” who “defined the Cold War era and fearlessly spoke truth to power. We will not see his like again. His loss will be felt by every book lover, everyone interested in the human condition.’’

Geller said le Carre died after a “short battle” with pneumonia. He is survived by his second wife, Jane Eustace, to whom he was married for almost 50 years. They have one son, the novelist Nick Harkaway. Le Carre and his first wife, Alison Sharp, have three sons, Timothy, Stephen and Simon.

“We all grieve deeply his passing,’’ Geller said.

Fellow writers paid tribute to le Carre. The master of horror novels, Stephen King, wrote on Twitter: “This terrible year has claimed a literary giant and a humanitarian spirit.”

Geordie Williamson, The Australian’s chief literary critic, said: “What made Le Carre extraordinary was the way he wrote himself out of genre and into larger eminence. His early novels were perfect of their kind.”

British historian and author Simon Sebag Montefiore said le Carre was a “titan of English literature’’ who created “his own world of masterpieces’’.

Le Carre’s mother left when he was five and he spent his childhood in boarding schools, which formed his view of the British class system. His father was a conman, jailed for insurance fraud, and an associate of gangsters.

He was open about his life when dealing with his biographer, Adam Sisman, but even then he held back on his time in MI5 and MI6. In an introduction to a 1991 edition of his novel Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, le Carre writes about the double agent Kim Philby.

“I knew that Philby had taken a road that was dangerously open to myself, though I had resisted it. I knew he represented one of the — thank God, unrealised — possibilities of my nature.”

Sisman’s biography, published in 2016, contains a surprise appearance by Donald Bradman. It’s 1948 and Bradman and the rest of the Australian cricket team are special guests at a lunch party at Ronnie Cornwell’s country house. Ronnie’s youngest son, David, the future le Carre, then 19, takes part in an afternoon cricket match.

Le Carre did not win the Booker Prize or the Nobel prize. He refused to allow his novels to be entered in the former. He can no longer win the latter as the author must be alive at the time the award is announced.

There’s a moment detailed in Sisman’s biography that is timely today. It’s 1987 and le Carre is lunching in London with the Russian-born writer Joseph Brodsky.

Brodsky’s wife rushes in with news: he has won the Nobel prize. Le Carre orders champagne and says, “Joseph, if not now, when? We’ve got to be able to celebrate our lives at some point.”