Universe swallows boy

His debut novel has sold a mind-boggling 100,000 copies, now Trent Dalton’s success story is about to exceed even his own wild imagination.

It’s hard to know where to start with Trent Dalton. He’s a storyteller by heart, one who is gifted or, as he puts it, cursed. “There’s this flaw in my system where I feel like I have to dazzle people with story. It’s like a sickness.”

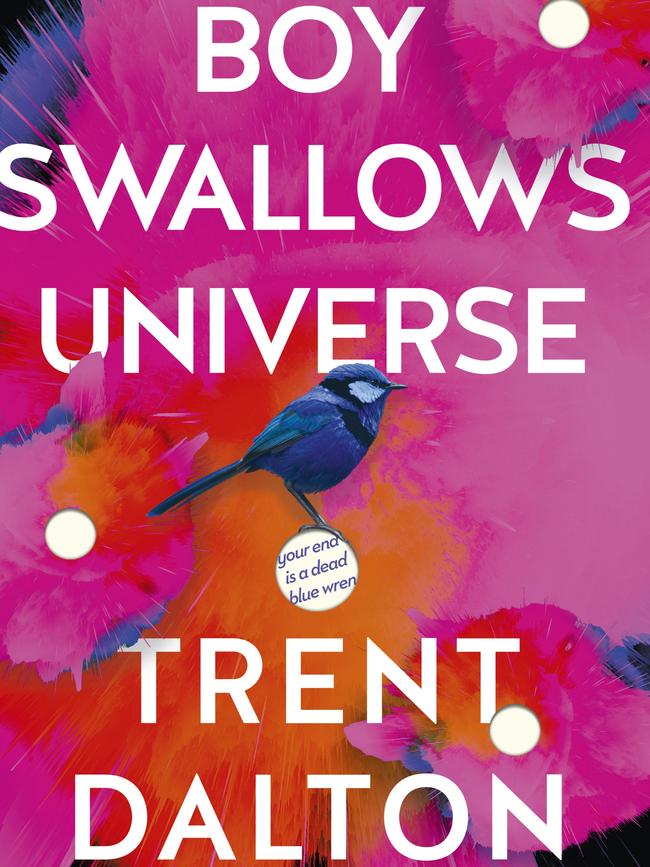

Perhaps we should start with his debut novel, Boy Swallows Universe, which has sold a mind-boggling 100,000 copies in less than 12 months and is almost certain to be adapted for film or television. Who or what was the inspiration for this dark, brutal, hilarious coming-of-age epic set in downtrodden early 1980s Brisbane, a book its author insists is a love story?

Well, to hear him tell it, the spark was his mother, who battled and beat drug addiction in the 1980s, commenting one day on the perfection of seeing Dalton’s two young daughters. Or it was the criminal Slim Halliday, a father figure to Dalton in real life and to his fictional alter ego Eli Bell in the novel.

Or it was the red rotary dial phone Dalton, aged six, and his three older brothers discovered one day in a drug dealer’s secret underground room, an antique that haunts the novel, and its creator. Or it was Keef, a stonefish sitting in a bottle of formaldehyde perched on the bookshelves in Dalton’s study in suburban Brisbane, overlooking him as he wrote the novel.

Personally, I think it was Keef, retrieved by the author’s father from a crab pot in the Pumicestone Passage between Bribie Island and mainland Queensland and named after the Rolling Stones guitarist. I think Keef and Dalton’s dad, who died of emphysema in 2014, are one and the same.

Dalton, who turned 40 this week, laughs. He thinks for a bit. “You may be right about that.”

When he first pondered writing about his childhood, a life surrounded by drug addicts, drug dealers, other criminals, some of whom he loved then and still loves today, he didn’t tell his mother or his brothers Joel, Ben and Jesse.

“The one person I did tell was my old man.”

Dalton, now a staff writer on The Weekend Australian Magazine, was doing his day job at the time and writing screenplays on the side. His father loved books and drink.

“I was writing everybody else’s ideas. My old man told me — we were having a few beers at his place on Bribie Island — that I should keep going, that I should knuckle down and do something big and ambitious.

“I told him I would like to write about some of that shit from the past. Now I have, and he’s not here any more and it kills me that he’s not. It was one little thing I got from him, that permission to go there.”

“There” is a surreal place, so much so that if Boy Swallows Universe were a memoir people would find it hard to believe. The novel centres on Eli Bell, who is 12, and his older brother August, who is 13 and has not spoken for six years because of a childhood trauma we will learn about.

Gus is smart and strong. He communicates with Eli by drawing signs in the air.

It is Gus who writes “Your end is a dead blue wren”, an ambiguous prediction that lingers in the novel to the end. It is Gus who writes “Boy swallows universe”.

It was August who taught me about details, how to read a face, how to extract as much information as possible from the non-verbal … It was August who taught me I didn’t always have to listen. I might just have to look.

Readers will of course wonder if Dalton is Eli or Gus. When I read the book I suspected he was Gus. Now I know the author a little more I realise that on one level that’s impossible. Being mute for six years? Dalton would be lucky to last six seconds. So Gus is mainly an amalgam of the author’s older brothers.

The boys’ mum, Frankie Bell, is Dalton’s mother, his “hero”, now in her 60s. In the early 80s she fell in love with a heroin dealer, named Lyle in the book, who became the boys’ stepfather.

“He has a special place in my heart,” Dalton says. Their real dad, who is central to the second half of the novel, is the author’s now-late father.

Halliday is, well, Halliday, infamous 1940s two-time escapee from Queensland’s Boggo Road Gaol who, the second time, was captured after three years on the run and convicted of murder.

Dalton and his brothers came to know him in the early 80s. The author considers Halliday, who died in 1987, a font of wisdom. This brings us to the question of why Dalton decided to write a novel rather than a memoir. His answer is fascinating. He knows that this book is only his perspective, drawn from his childhood memories.

“I know my version of the story is not the bona fide facts,” he says. When his oldest brother Joel read the book, “he said, ‘Mate, I love this book but I can’t believe you saw it this way’.

“He knows I saw it through my younger brother eyes. If Joel wrote the book,” — here Dalton gestures to a copy on his desk, with its bright pink and orange cover — “the cover would be black, and it would be a Cormac McCarthy-esque tale.

“He wouldn’t be afraid to go into the true darkness of it. The things I, as a kid, saw as wondrous, he saw as reality. The things I mythologise and romanticise he saw through near-adult eyes.

“And that, man, is why he’s King Arthur. He’s the guy who got myself and my brothers through life. I owe him my life. And he defends this book in the same way he defended me as a kid.”

As for his mother, he thinks he has put one-tenth of her real story into the novel. “My mum’s memoir would be amazing. I have told her 1000 times that she’s got to write it. Everything that’s in the novel happened, and then there’s me putting the wishful thinking on it.”

He wrote the novel to tell his mother he loved her and that she must never think that her mistakes of the past can reduce that love, then or now.

She likes the book, too, and her support and that of his brothers is important. He knew the risk of writing their lives. He worried some people would read the novel and consider it the opposite of a love story.

Here’s Eli seeing his mother’s room after she goes cold turkey.

The sky-blue walls were covered in small holes the size of Mum’s fists and emanating from these holes were streaks of blood that looked like tattered red flags blowing in battlefield winds. A long brown streak of dried-up shit wound like a dirt road to nowhere along two walls.

And here he is returning to live with his father after Lyle falls foul of the law.

His shorts are soiled with his own piss. He grits his teeth, spit coming from his mouth. Trying to say something. Trying so hard to form words. He sways as he stares at me and finds his balance. “UUUUUuuuuuuuu …” he spits. He wets his lips and says it again. “UUUUuuuuuuuu.” Then he goes again. “Cuuuuuuuuuunt,” he spits, breathless, struggling to find the word … “Cuuuuuuuuuunt,” he screams.

“Yes, my great fear was that people, at an event, would stand up and say ‘How could you love those people?’” Dalton says.

“That they would miss the point I’m making: that love conquers all. I know that’s the cheesiest thing, but it is an absolute fact in the Dalton family.”

This has not happened, and the author now thinks he understands why.

“I realise that I was an idiot, that I forgot that people who read books are an evolved species. They are past knee-jerk reaction. They are past all the things that drag the world down because books have taught them to go past that. They are the people who come to events and say, ‘You know what, that woman, that Frankie Bell, that’s my mum.’ ”

Dalton spent two years writing the novel, working in the room where we talk, under Keef’s unblinking eye, from 8pm to 10pm after his daughters, now 12 and 10, went to bed.

Early on he asked his wife, Fiona, a journalist who works as a media adviser for Arts Queensland, not to tell anyone he was writing a novel because “there’s nothing worse than people asking ‘How’s the book going?’ ”

When he finished the manuscript he sent it to Catherine Milne, head of fiction at HarperCollins. In response he received not the “Thanks but no thanks” he expected but an effusive “Yes please, we will publish this”.

“I turned to my wife and said, ‘What the f..k have I done?’ I swear I said that. I wrote it thinking it would never be published, and there’s a great freedom in that, an unbridled licence to go for broke. I felt there was nothing to lose.

“But now it was real. It was going to be published. Then all the consequences came to me. I realised this book was drawn from my life, could affect people I love. I went through this deeply important process, thinking ‘What if Mum won’t talk to me any more because of some book I wrote?’ ” So he did what he had resisted doing for two years: he let the genie out of the bottle.

“I called up Mum and I said, ‘Mum, I’m sorry. You could have raised a carpenter and I would have built you a cupboard, but you raised a writer and I’m sorry but I’ve written a 470-page book about you.’”

That book, with his mother’s blessing, is now one of the biggest literary success stories in Australia. Dalton’s events at the Sydney Writers Festival this coming week are sold out. The organisers have moved him to bigger venues to accommodate the crowds. On Monday night he is in the running for two awards, best novel and best debut novel, at the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards. On Thursday night Boy Swallows Universe is on three shortlists, literary fiction, debut fiction and audiobook, at the Australian Book Industry Awards. The Miles Franklin longlist will be announced early next month.

The book has been sold into the US, receiving a glowing review from writer Ellen Morton in The Washington Post (“hypnotises you with wonder, and then hammers you with heartbreak”) and elsewhere around the world.

In the awards next week, Dalton will go head-to-head with the writer he has been compared with, four-time Miles Franklin winner Tim Winton, who is in contention for his latest novel, The Shepherd’s Hut.

When I mention this Dalton laughs.

“I am not worthy to wax his surfboard.”

When I joke that Winton will not be at the awards because he has chained himself to Ningaloo Reef, the World Heritage site he is striving to save, Dalton nods enthusiastically.

“He is a dead set legend!”

Dalton is perhaps the nicest person I know. He says thank you, to everyone and anyone, more times than even Emily Post would deem necessary.

Later on, when we have left his house and set ourselves up at the weekly trivia night at the local bowling club (he’s great at music, terrible at geography), I ask him if he has ever done anything bad. He talks around it and then returns to it about an hour later, with me having to re-ask the question. Yes, he admits, as a kid he once nicked a packet of chewing gum from a corner store.

Having read his novel, it’s tempting to see a psychological link between who he was and who he is now, to presume he has worked to turn the inner darkness of his childhood into the bright exterior of his adulthood.

When I put this to him, he pauses for the longest time in the hours we have spent together.

He starts to answer, “I wanted Eli Bell to do the things I never did …”, but then he breaks off and pauses again.

He then says he will tell me the truth about himself. In what follows his use of the word “built” is telling.

“To be honest, there were all these feelings I had and I threw them inside a box inside myself. Then I built a gregarious Australian journalist, a, you know, happy guy, around that box that carried every fragile and dark thing.

“I built this guy who pretends he’s afraid of nothing but in fact he’s terrified of that box opening up.”

Then, two years ago, “it was, f..k it, that box is the core of me, it’s the core of my brothers”.

“And that’s what the book is about. Just own it, swallow it, the good stuff, the bad stuff. So I stepped into the shoes of this beautiful kid I’ve created who’s called Eli Bell, who is savvier than me and smarter than me and tougher than me, and it’s him who was able to go inside and open that box.”

Dalton is now at work on his second novel. He feels that Eli Bell has freed him to access the “galaxy of yarns inside my head”. When I note that Kurt Vonnegut felt the same way about Billy Pilgrim and Slaughterhouse-Five, Dalton is gobsmacked. “Stop it! I’ve been reading it, again. It is a masterpiece and he was a genius.” His new novel is about two young women, “in over their heads” who go on “an amazing odyssey”.

“Sorry to sound all writer wanker,” Dalton says, “but it’s about gifts that fall from the sky, curses we dig from the earth and the secrets we bury inside ourselves.”

“It will either be the greatest Australian Odyssey or it will be the biggest fattest turkey ever written.” Either way, as Vonnegut noted and Dalton now knows, “so it goes”.

Trent Dalton will be at the Sydney Writers Festival from Monday. www.swf.org.au

-

In the Know

Born: Ipswich, Queensland, 1979.

Educated: Bachelor of arts in creative writing at the Queensland University of Technology. Deferred for a job at Brisbane News. Never finished degree.

First story ever published: Story on a firefighter who ran endlessly up and down a lighthouse stairwell carrying his dog. Published in 2000 in free glossy colour magazine Brisbane News. “This yarn was everything I love about journalism. The extraordinary in the ordinary. The magnificent in the mundane.”

Awards: This year Boy Swallows Universe was named Indie Book Awards Book of the Year and won the Mud Literary Prize. Dalton is a two-time Walkley award-winner, four-time Kennedy award-winner for excellence in NSW journalism, four-time News Awards features journalist of the year, and was named 2011 Queensland journalist of the year.

Career highlights: ‘Why am I here?’ I asked the Dalai Lama after two days in his company for a magazine profile. I wanted to know the meaning of life. I really meant, ‘Why are we all here on this batshit crazy rock?’ But he kindly narrowed the focus. ‘You’re here to tell stories,’ he said. ‘That’s all you have to do.’ That was nice of him to say and nice for me to know.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout