The Dismissal: Palace letters shed light on a PM kept in the dark

Hocking initially requested the letters from the Australian Archives in 2011 but was refused on the basis they were not a “Commonwealth record”, and so not liable to be disclosed, but personal correspondence between Kerr and the Queen’s private secretary, Sir Martin Charteris. It might be noted that at this time the Gillard Labor government held office.

Over the next decade Hocking continued to press for the release of the documents and in late 2016 began proceedings in the Federal Court. She lost before a single judge, then lost 2-1 in the full Federal Court and finally succeeded 6-1 in the High Court in 2020.

The archives spent more than $2m of taxpayers’ money in resisting the claim. It takes no acquaintance with Canberra, however, to know that the archives would not have engaged in this scandalous exercise without the support of the relevant ministers and departments in the governments, both Labor and Liberal, over this whole period. Which is what makes Malcolm Turnbull’s view in the book’s foreword that the letters should always have been released rather bewildering, given that any time over his three years as prime minister he could have done just that, whatever the concern of the palace might have been.

All this required considerable courage on Hocking’s part because of the costs orders that she might have faced if the litigation had turned out to be unsuccessful, even though the courts well into proceedings placed a cap on her possible liability because of the public interest nature of the case. Some funds were also raised from public donations.

There are 212 letters with many of Kerr’s being lengthy and showing him constantly meddling in political questions outside the proper role of a governor-general. In addition, he spent enormous amounts of time on pomp and pageantry. What is one to make of this record by the British High Commissioner in Canberra in 1974: “I went over this ground with Sir John Kerr in a private talk … he told me that he was trying to think of a way around the difficulty of the pattern contemplated by Mr Whitlam for the playing of the national anthem.”

Hocking takes a sharply different view of the correspondence between Kerr and Charteris from Paul Kelly and Troy Bramston in their recent book, The Truth of the Palace Letters. She argues that Charteris, and so effectively the Queen, were aware of what Kerr intended to do and actively encouraged him in this course.

I doubt so much can be read into the correspondence. It needs to be remembered that Charteris was a courtier whose role was to flatter and defer to not only his royal employers but even a tiresome Australian governor-general. Consider this oleaginous exchange when Kerr asks, “Perhaps you could let me have an indication as to whether or not there is too much or too little detail in the kind of communication that I have been sending to you.” Charteris responds: “I have no hesitation in saying that they seem to me to be just about right.”

It can also be doubted that Kerr’s removal of the government was the palace’s preferred resolution of the impasse in Canberra, given that this was bound to provoke a controversy about the Queen’s role in what occurred.

It is true there was no scope for the palace to warn Whitlam as this would have been an interference in Australian political affairs. Nevertheless, there is something bizarre about the fact Kerr’s likely course of action was known to the palace, and so to the Queen, but completely secret from Whitlam and his ministers.

In all the criticism of Kerr’s failure to warn Whitlam and the abuse of judicial office by Chief Justice Sir Garfield Barwick and his High Court colleague Sir Anthony Mason, it is important not to overlook the conduct of Malcolm Fraser and his party as the instigators of these events or the fact they would probably have had no excuse for blocking the budget in the absence of the Loans Affair.

Hocking concludes that all this indicates the need for an Australian republic. And so it does. But not one with an elected president who could set himself or herself up, in the way that Kerr wanted to do, as a rival to the prime minister.

In any event, this provocative book demonstrates there is still considerable room for argument over the events of November 1975.

Michael Sexton’s books include Gough Whitlam: The Rise and Ruin of a Prime Minister.

-

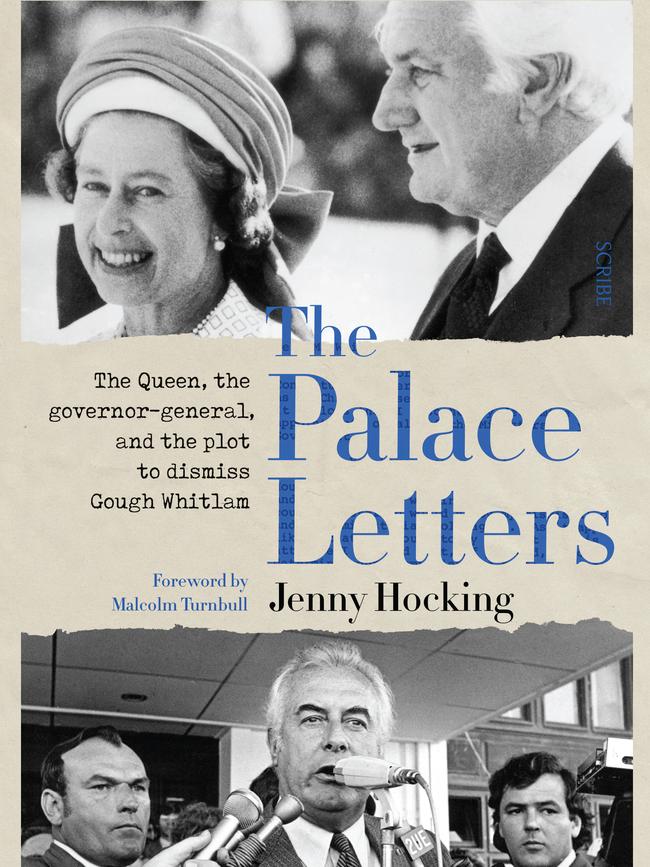

The Palace Letters: The Queen, The Governor General and the Plot to Dismiss Gough Whitlam By Jenny Hocking. Scribe, 265pp, $32.99 (PB, $12.99 (ebook)

Jenny Hocking, who secured the release of the palace letters, has written an account of the protracted legal proceedings that achieved this result and added a political analysis of their contents that is highly critical of then governor-general Sir John Kerr and the palace itself.