Mistaken identity claim in Holocaust sex slave tale

The family of a woman at the centre of Australian Heather Morris’s new book has questioned her depiction by the author.

The family of a woman at the centre of Australian Heather Morris’s new book has questioned her depiction by the author, saying key elements of the Holocaust survivor’s appearance suggest a case of mistaken identity.

“I think that she (Morris) has got the wrong person,” says George Kovach, whose late stepmother, portrayed as a sex slave, is the main character in Morris’s newly published Cilka’s Journey.

Cecilia (Cilka) Klein, who died in 2004, was 16 when sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in World War II. When the camp was liberated by Russian troops in 1945, she was accused of having slept with the enemy and sentenced to 15 years in a Russian hard labour camp.

While Klein spent the remainder of her life in comparative obscurity in Slovakia, she became internationally known early last year when she was depicted as a sex slave in Morris’s debut book.

Based on the life of Melbourne Holocaust survivor Lali Sokolov, The Tattooist of Auschwitz has become an international bestseller, with more than three million copies sold. It has also been the subject of a major fact-finding report by the custodians of Auschwitz, alarmed at the extent of its historical inaccuracies.

During some of the many discussions that formed the basis of The Tattooist of Auschwitz, Sokolov spoke about Klein, the woman he claimed had saved his life at Auschwitz and who, he told Morris, was “the bravest person I ever met”.

Following countless reader inquiries about Klein’s fate, Morris made her the basis of her second book, published last month. Morris recently told The Weekend Australian that although her book was marketed as fiction, it was a “pretty accurate” account of Klein’s life, based on her own visits to Slovakia and the help of researchers.

According to the blurb for Cilka’s Journey, when she was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1942 the teenage Klein attracted the attention of a senior Nazi, who later repeatedly raped her, thanks to “her long beautiful hair”. Unlike other forcibly shaved prisoners, Klein was allowed to grow her hair. In a taped interview in 1996 with the University of Southern California’s Shoah Foundation, Sokolov spoke of an unnamed Auschwitz inmate, “a very beautiful girl, Jewish girl, the only girl in the whole camp whom the SS allowed to keep her hair”.

And Sokolov’s son, Gary, who visited Czechoslovakia in the 1970s with his mother, Gita, recently told The Weekend Australian about meeting his mother’s old friend, who he believed was Klein. “I do remember how stunning she was.”

But Klein’s family has questioned if this woman was their relative, saying the descriptions do not fit. “My stepmother might have been cute when young, but she was never a great beauty, nor did she have the lustrous black hair that Heather (Morris) gives Cilka,” says Kovach.

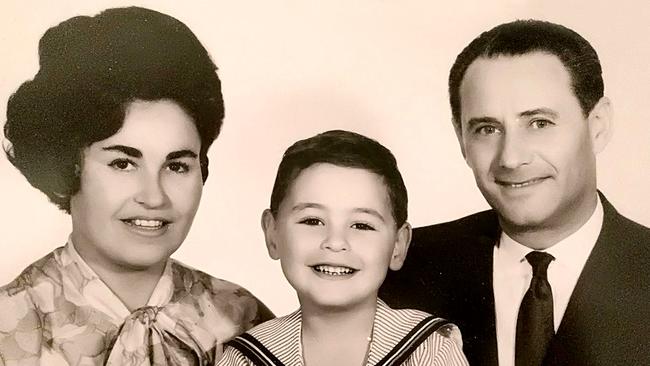

He has provided The Weekend Australian with a photo of his stepmother from the 1970s, around the time Gary and Gita Sokolov visited Czechoslovakia.

“Although she is perfectly presentable, no one would describe her as ‘stunning’,” he says.

While Gary Sokolov could not be contacted for this story, he told Kovach recently that the woman in the photo did not look like the one he had met with his mother.

“The more I delve into this the more I am convinced that the beautiful woman with the long black hair spoken of by Sokolov in his Shoah interview was not my stepmother,” says Kovach, who has questioned other inconsistencies.

In his 1996 testimony, for example, Sokolov said he had visited the beautiful woman after the war in Paris. “She was living in King George hotel, very luxurious, she was married, she had a boyfriend, a very rich boyfriend, and her husband … the boyfriend gave him a job, which he went all over Europe and bought tanks.”

But Kovach says his stepmother only visited Paris once — for a few days in 1968, during the brief period of the Prague Spring in which she and her husband, Ivan, were able to travel.

“They certainly weren’t staying at the George V,” he says of the luxurious Parisian hotel to which Sokolov was presumably referring. “They had no hard currency. In their suitcase, for their one trip to Europe, they took food with them because they couldn’t afford eating out.”

The Weekend Australian is not suggesting Morris has acted inappropriately, only that Klein’s family says she may have made a mistake.

Kovach is Klein’s closest known relative. In April, six months before Cilka’s Journey was published, he was visited at his home in California by Morris, who was seeking photos and asked him to write an afterword to the book — both of which he declined. “Did she ask me anything about my stepmother? No, I don’t think she did,” he says.

Neither Morris nor her publicist responded to requests for a comment.