But neither these machines nor the money they help make mean much when it comes national identity. They are mere expressions of energy or promissory notes. What such efforts can do is lay the economic ground for the transformative attentions of creative spirits: those who bring self-consciousness, craft, talent and insight to the story of living as part of a particular group in a given time and place.

December last year marked the 80th birthday of Meanjin, one of our oldest and most storied journals of literature and culture. Founded by Clem Christesen in Brisbane in December 1940 — a fragile pamphlet of poetry and prose launched into the chaos of wartime — and based since the latter part of that decade in Melbourne, Meanjin has furnished the other half of our national story. It has served as archive and barometer of the development of a distinct antipodean culture.

Meanjin was the cosmopolitan journal that provided reports from Paris by Christina Stead and published Jean-Paul Sartre and JM Coetzee. It was also the defiantly parochial magazine where AA Phillips coined the phrase cultural cringe. Meanjin dedicated issues to feminism, multiculturalism or indigenous culture long before those subjects were of mainstream consequence. It was in Meanjin’s pages that writers and thinkers disparate as Manning Clark, Helen Garner, AD Hope and Alexis Wright laid out their wares.

Current editor Jonathan Green registers the historical significance of Meanjin Volume 79, No 4 by inviting every extant former editor of the journal to say their piece in its opening pages. Collectively, their tone is a mixture of pride and dudgeon. So much good writing to praise; so many important causes taken up. But too much of it published under conditions of economic precarity, or in the face of bureaucratic inertia and political displeasure, or during a period in which a shift to digital undermined the model on which little magazines such as Meanjin were based.

Likewise, the content in this number — in which figures of note are asked to look forward to Meanjin’s (and Australia’s) next 80 years — mostly reflects ambivalence, with hope and anxiety jostling for ascendancy.

For author Jen Mills, who supplies a fictitious transcript of an interview undertaken in 2099 with her uploaded consciousness (long archived in an Adelaide library), there is the weird experience of seeing our 21st-century future viewed with retrospective lucidity.

Of the ecological collapse that ran alongside technological innovation during the 21st century, Mills’s AI avatar says: “My generation didn’t do enough to tear it all down. We tried, but we should have tried harder. We didn’t understand our own power.”

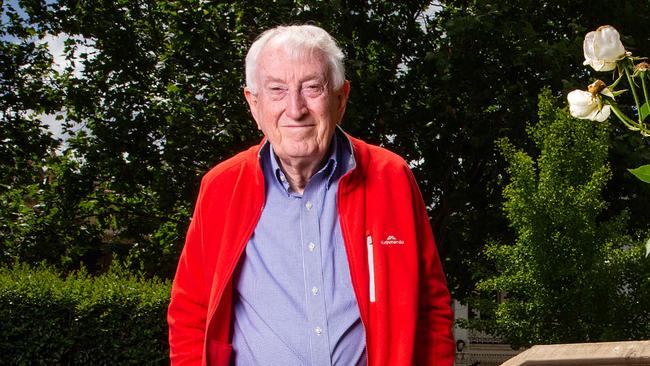

For Nobel prize-winning scientist Peter Doherty, at age 80, looking backwards is anything but a fictional effort. His essay draws on decades of experience to argue for a series of future shifts, from a universal basic income to an Australian back-to-nature movement.

Michael Mohammed Ahmad writes with wit and ferocity about being an Australian citizen whose Lebanese ethnicity renders his relationship to our broader polity perpetually fraught. Philosopher Raimond Gaita outlines the hard moral philosophy at work in a society up-ended by COVID-19. Tim Dunlop counts the cost of economic precarity on a new generation of jobseekers. And Jane Rawson wonders in a puckish and learned piece where the line between native and introduced species should be drawn.

Each of these pieces is excellent in its way — animated by anger, curiosity or compassion. And their cumulative impact is to render porous the boundaries between literary forms and the subjects those forms discuss. It reminds us that what small magazines do best is present an ecology of idea and argument on a graspable scale.

Christesen saw the journal as a means to encourage the flourishing of thinkers and creative artists — a guild of responsible, informed, judicious, socially conscious individuals — who together might serve as a bulwark against cultural sterility or emergent authoritarianism. Which, given the temper of our times, means Meanjin’s effort to tell the other half of Australia’s story remains as necessary as ever.

Geordie Williamson is chief literary critic of The Australian.

-

Meanjin Volume 79, No 4: The Next 80 Years

Edited by Jonathan Green

Meanjin, 170pp, $24.99 (PB), $9.99 (ebook)

Meanjin Volume 79, No 4: The Next 80 Years

Edited by Jonathan Green

Meanjin, 170pp, $24.99 (PB), $9.99 (ebook)

It is too often the case that only half of Australia’s story gets told. Think of those perennial resource company commercials featuring giant mining trucks driven by fair-dinkum types in helmets and hi-vis. As synecdoches for the industriousness and ingenuity required for the generation of our nation’s material wealth, they are eloquent and imposing.