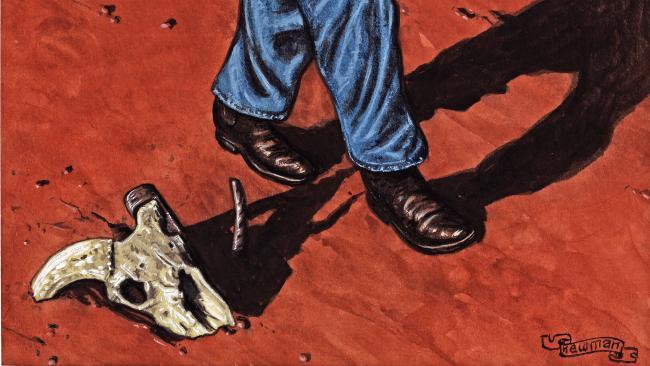

Heroic take on manhood

LEAF through Oscar Wilde's student copy of Nichomachean Ethics and you will find, scrawled in a margin, the following gloss on Aristotle's text:

LEAF through Oscar Wilde's student copy of Nichomachean Ethics and you will find, scrawled in a margin, the following gloss on Aristotle's text:

"Man makes his end for himself out of himself: no end is imposed by external considerations, he must realise his true nature, must be what nature orders, so must discover what his nature is."

When Colts Ran is an epic of Australian manhood that unfolds in the light of Wilde's passionate imperative. While the novel's operatically large and varied cast manages to inhabit almost every point of our nation's recent history, its narrative range across millions of wild acres and thousands more tamed by the plough, this threnody -- a mourning song for the kind of man once "Made in Australia" (to give the work its earlier title) -- is the one motif that returns.

There has always been something of the 18th century about the fiction of Roger McDonald, who won the Miles Franklin in 2006 for The Ballad of Desmond Kale. When Colts Ran shares with his earlier novels a vibrancy, expansiveness and love of the picaresque. It, too, is concerned with a largely homosocial world, country Australia in the postwar era being one of the few places where the Regency swagger of the Anglo past could be replicated without seeming absurd.

Even our hero, Kinglsey Colts, whose long life provides the skein to which all subsidiary yarns are tied, is a creature of echoes. We meet him one night during World War II, an absconding boarding schoolboy leading a gang down to the harbour, where they steal a craft and row between massed warships to enjoy a smoke beneath the bridge, their heads tilted back to admire the "arch bulked over them, riveted in grey". Tellingly, this is the same attitude in which we meet Syms Covington, Mr Darwin's shooter. In McDonald's 1998 novel of that name the young protagonist swims through a Bedfordshire river lock, the iron bars and wooden planks above him like a premonition of his shipboard life to come. Divided by centuries and hemispheres, both Syms and Colts grow to be strong, capable men who nonetheless live in the shadow of still larger figures.

For Colts, it is his adoptive father, "Dunc" Buckler, a Great War hero and womanising rogue whose adventures in the Top End during the war, travelling between stations to commandeer equipment in case of Japanese invasion, inspires the younger man to light out to for the territory. Buckler finds a place for the youth at a station, under the wing of an older jackaroo, Randolph Knox, a cricketing hero of Colts's at school.

The relationship between this two will define the novel's course. Knox, the earnest, industrious, and rather prim scion of a grand country family; and Colts, the impetuous, restless, and charming foundling whose devotion to Buckler's adventurous ways threatens to send him off the rails. For a while, at least, the two very different characters balance each other out. Colts goes off to war but comes to live and work afterwards in the Isabel district, a beautiful swath of sheep country largely owned by the Knox family. In time, though, Randolph Knox's fondness for his friend gives way to something deeper; and it is his greed for Colts's love that breaks their bond.

For the author, it is as though the failure of this friendship marks the end of a timeless, paradisal moment: henceforth, history rushes in, and the canvas widens in ways that are exhilarating and confusing in equal measure.

The apocryphal town of Isabel Junction moves to the centre of events; and, from its streets and surrounds, younger generations of men emerge to be tested against their elders and found wanting in ways that alter with the decades.

It is an uneasy shift, though: as though the sprawling genealogies of Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha County had been grafted on to the Cambridge chapters of Brideshead Revisted. McDonald's prose, too, which has always been an odd mixture of compressed meaning and freewheeling sense, becomes even more muscular and oblique here.

It is dense and heady stuff, closer to Les Murray's poetry than to most novelists. His is a language designed to celebrate place from above:

Isabel Junction was a town of rusting metal roofs and termite-eaten verandah posts emblematic of the Australian scene. Tragedy came from the shadows of clouds, wind in the hill's puffy cheeks brought it on -- drive your car into a tree, fry yourself on an overhead line, drown in your bath, allow two giants their moment of self -destruction. The Greeks had a name for it: goat-song.

Tragedy, indeed, is the other name the Greeks gave goat-song, and it helps to read the wilder and more diffuse middle sections of When Colts Ran with this old idea of human drama in mind. The means (car crash, football accident, a fondness for booze) may be different, but the ancient notion that pleasure and empathy might be paradoxically awakened by the recounting of tragic events is what links the various narratives of a tiny community in rural NSW with the West's seminal dramatic form.

McDonald's use of different-angled lens throughout makes for a complex and ambitious work. On one hand, the author seeks to join the Australian novel with a form inaugurated 2500 years ago in classical Greece and brought to a fresh perfection in our language by Shakespeare two millenniums later; on the other, he is attempting to conflate a national type with an individual.

Only after widening its gaze to encompass the many micro-tragedies of our nation's rural culture, a region and a people whose political clout and sociocultural resonance has diminished with the years, does the novel's focus narrow once more, to visit the failure of a single man.

Having struggled through the thick scrub of these mid-sections, the final chapters of When Colts Ran open on to lush, clear pasture. The reprise of the few central stories is elegiac in tone and muted in volume; the reader can feel the narrative returning to stillness and the final tableau of two old men, now-reconciled, living together outside a much-changed country town.

For the long-dead Buckler, men were either "Goats" or "Kings".

Colt's tragedy is to live as though these inherited demarcations were real and absolute. In this rich, beautiful, and magnificently flawed novel, McDonald shows how our true natures often lie in between.

Geordie Williamson is The Australian's chief literary critic.