Genius of James Joyce remembered in centenary year of Ulysses

On Bloomsday, June 16, literary minds young and old revisit Joyce’s masterpiece.

James Joyce was the kind of Catholic who understood the power of a feast day. So he would have approved of Bloomsday because June 16 was the day he first went out with his wife-to-be, Nora, the woman on whom he modelled his most vivid and eloquent creation, Molly Bloom.

It’s also the day in 1904 on which all the complex and variegated action of his novel Ulysses is set, as if an epic – to rival Homer’s Odyssey, or Shakespeare’s Hamlet – could be confined to a mere day in long-ago Dublin, whose racy idioms and tossed-off obscenities sound just a bit like the world we hear all around us.

There’s another reason to be particularly celebratory of Bloomsday this year because it’s the centenary of the publication of Ulysses in 1922.

One of the most notable critical interpreters of Ulysses, Sam Goldberg, used to run the English department at the University of Melbourne like an emperor. The story went that Goldberg refused to rewrite his doctoral thesis at Oxford but went on to publish it as The Classical Temper, a book that received the supreme backhanded compliment from the most brilliant of the Joyce wizards, the Canadian-born Hugh Kenner, who said it was how Ulysses would read if it were a novel but it wasn’t.

So Melbourne has its connections with Ulysses. Vincent Buckley, the poet-professor who disagreed with Goldberg about most things, was an enthusiast for Ulysses. His ancestral Irishness and Jesuit-inflected education brought a particular empathy to it, as it did to any other great Irish writer from Jonathan Swift to Seamus Heaney. And it was under Buckley’s supervision that the barrister-to-be, Mick Crennan, wrote a master’s about Ulysses.

It was a fine thing to go with Crennan last year and sit in the extramural seminar on Ulysses conducted by Ronan McDonald, an Irish Studies professor who thinks the Bloomsday book Ulysses is too important to let it lapse in a world where great books get overlooked. He runs the seminar at Newman, the Jesuit college at the University of Melbourne where Walter Burley Griffin’s buildings appear medieval and modernist at the same time.

And it was splendid to sit in the room of Newman’s rector, Frank Brennan, with plenty of wine and good cheese, and listen to the bright young things and the old timers as they made their way through the book that all books in English – at least those that aim to break barriers and make things new – take their bearings from.

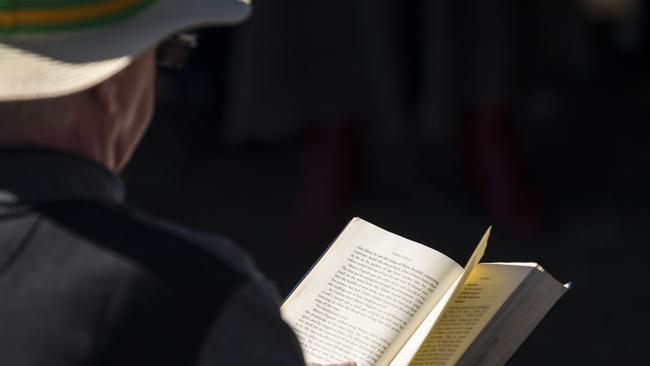

Brennan sat with his copy of Joyce’s masterpiece open as we chewed over the mystery and magic of Bloom’s wanderings about Dublin as he encounters Stephen Dedalus – that latter day portrait of the artist Joyce – and mourns his betrayal by the woman he loves, Molly Bloom.

There’s a story in Plato’s Republic about the great heroes choosing what they would be reborn as. Odysseus doesn’t get around to it and has to cop coming back as an ordinary man. But then he discovers it was the best possible thing that could have happened to him.

Stephen is an extraordinary young man, a genius in the making, though we catch on fairly soon that he will have to learn to make something of Leopold Bloom if he is going to turn into someone who could write the book he’s a character in. We see him teaching at school and looking with pity at an awkward boy who must have been sustained as Stephen was by a mother’s love.

“Ugly and futile: lean neck and tangled hair and a stain of ink, a snail’s bed. Yet someone had loved him, borne him in her arms and in her heart. But for her, the race of the world would have trampled him underfoot, a squashed, boneless snail. She had loved his weak, watery blood drained from her own. Was that then real … Amor matris: subjective and objective genitive … Like him was I, these sloping shoulders, this gracelessness. My childhood bends beside me.”

The thing that tries the patience of everyone who reads Ulysses is the way Joyce circles around and around the same obsessive material. The action – such as it is – is constantly interrupted by brooding obsessions and all sorts of tossed-out privacies that can be thrilling in their strangeness but which we don’t understand. It’s as if we’re inside someone’s head without a guide to where we are.

That’s why Salman Rushdie can say of Ulysses, “There are stories inside Ulysses but its primary impulse is not narrative.”

Leopold Bloom is a much more mature person than Stephen and he’s also, in terms of the language with which he tries to shape the world, a bit of a dill. Here he is at Paddy Dignam’s funeral: “The resurrection and the life. Once you are dead, you are dead. That last day idea. Knocking them all up out of their graves. Come forth, Lazarus! And he came fifth, and lost the job.”

The joke is weak and the verbal sense is hopeless but it touches something in everyone because Bloom is a highly individualised everyman figure who is also – that’s the trick of it – the myriad-minded Ulysses. And somewhere in the feeble jokiness there is also a genuine sense of reverence. He thinks of all the dead bodies the priest sprinkles water on:

“… baldheaded businessmen, consumptive girls with little sparrow’s breasts. All the year round he prayed the same thing over them all and shook water on top of them, sleep. On Dignam now.”

Nothing is more extraordinary in the history of literature than the way Joyce creates a kind of poetry out of the humdrum and hackneyed phrases that tumble through Bloom’s mind. Bloom is saddened because he knows that his wife Molly is having an affair with a man called Blazes Boylan and Joyce adjusts the lens of the language to whatever is going on. Lunchtime will be full of the language of food and drink but also the excruciation of betrayal.

“Stuck on the pane two flies buzzed, stuck … Ravished over her, I lay, full lips full open, kissed her mouth. Yum. Softly she gave me in her mouth the seedcake warm and chewed. Mawkish pulp her mouth had mumbled, sweet and sour with spittle. Joy: I ate it: joy. Young life, the lips that gave me pouting, soft, warm, sticky gumjelly lips. Flowers her eyes were, take me, willing eyes. Pebbles fell. She lay still. A goat. No-one. High on Ben Howth rhododendrons a nannygoat walking surefooted, dropping currants. Screened under ferns, she laughed, warmfolded. Wildly I lay on her, kissed her; eyes, her lips, her stretched neck, beating, woman’s breasts full in her blouse of nun’s veiling, fat nipples upright. Hot, I tongued her. She kissed me. I was kissed. All yielding she tossed my hair. Kissed, she kissed me.

Me. And me now.

Stuck, the flies buzzed.”

Bloom is, as the idiom has it, stuffed. But the atmospherics of food leads to the image of himself as a trapped fly or the witness of creatures who are stuck.

It’s a great cathedral of a book, and it’s nice to think of the kids and their elders taking it in with a supple Irish teacher like Ronan McDonald.

The careful gauging of effects and the reconsideration of what a given term means will repay anyone with the time to sift the subtlety of Joyce’s effects, even if they’ve stared down the prospect of a doctorate about Ulysses.

Joyce said once that you had to insert enough puzzles to keep the professors busy for centuries and that was the only way to ensure your immortality. Well, it’s also a hilarious hoot of a book. Joyce also said, “Some of my methods are trivial and some are quadrivial”, referring to the quadrivium, the medieval methods of systematising knowledge.

It’s worth remembering that Australians are as good at caricature as the Irish are, partly because it’s easier to laugh at yourself if you’re inclined to think of the world as somewhere else, a place governed by smooth, autocratic figures (call them imperial if you must).

Edna Everage is a Joycean figure and so – with bells on – is Sandy Stone. Anyone who has been in an audience with Barry Humphries as Sandy Stone and found themselves convulsed with laughter one minute and weeping the next might reflect on the tragicomedy of his art that’s a bit like Joyce’s. You might even say the gap between Humphries’ awful Australians and the patrician figure, elegant and highbrow, who once said, “I’m not an Australian, I’m a Victorian” is a bit like the abyss that separates Bloom and Stephen.

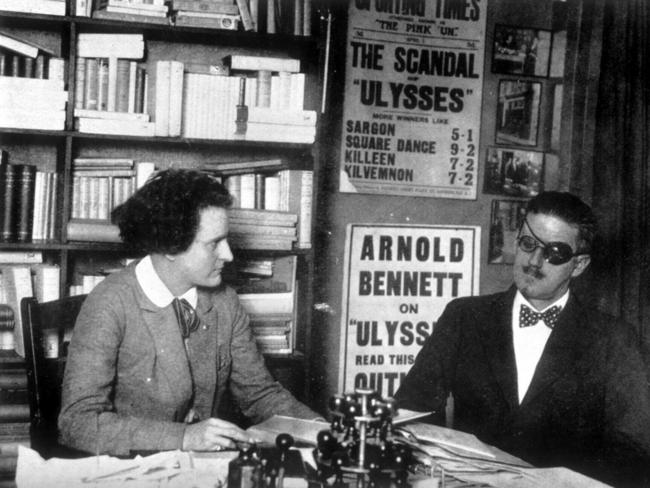

American novelist William Gaddis – like David Foster Wallace, an inheritor of Joyce’s innovations – said that as a young man he read the dirty bits of Ulysses first. And it’s the pure, rhapsodic raunchiness of Molly Bloom that’s so marvellous, as well as her ability to make musical the full stretch of Irish blarney.

Here’s a bit of Molly, almost at random. It’s unpunctuated but you’ll get the gist:

“… no that’s no way for him has he no manners nor no refinement nor no nothing slapping us behind like that on my bottom because I didn’t call him Hugh the ignoramus that doesn’t know poetry from a cabbage that’s what you get for not keeping them in their proper place pulling off his shoes and trousers there on the chair before me so bare-faced without even asking permission and standing out that vulgar way in the half of a shirt they wear to be admired like a priest or a butcher or those old hypocrites in the time of Julius Caesar of course he’s right enough in his way to pass the time as a joke sure you might as well be in bed with what a lion God im sure he’d have something better to say for himself an old Lion would…”

After Joyce died in Zurich in 1941 he was buried near the zoo and Nora, the model for Molly, said: “My husband was very fond of lions. I like to think of him lying there and listening to them roar.” Molly herself roars and testifies to the power of a love that outstares its own inconsistencies. This vision of Ulysses is articulated in that quote from Saint Augustine about how things can be good but not supremely good and therefore corrupt at the same time. Joyce brings a tragicomic poise to that perspective and an overall sense of creating a modern epic poem even though he has hand-me-down language to work with. That makes Ulysses a bit of a joke, though an encyclopedic one that yields all the riches of the earth.

Oscar Wilde, a different kind of Irish tragicomedian, said that nothing of any importance can be taught. It’s pleasing that McDonald and his fellow devotees are nevertheless bearing witness to a great book that is now beyond the syllabus. It’s lovely to think of them listening to Ulysses in an audio version like the one produced by RTE in 1982, or to the “genius”, as Buckley called it, of Molly Bloom’s climax performed by the great Irish actress Siobhan McKenna.

May they have a great Bloomsday, may the beer be sweet and the Guinness biting as they honour Joyce’s great story of a wanderer, a wife, and a bright young man.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout