Darrieussecq’s Being Here traces life of Paula Modersohn-Becker

The short but productive life of German expressionist painter Paula Modersohn-Becker has gone under the microscope.

When Marie Darrieussecq’s first novel, a surreal fable of sexual adventure and metamorphosis called Pig Tales, was published in France in 1996, it was a sensation and sold more than 300,000 copies.

Two subsequent novels, All the Way and Men: A Novel of Cinema and Desire, each with a thread of romantic optimism running through them, observed that girls and young women tread a lot of metaphorical water waiting for the “right” man to swim into view.

In an interview last year with The Australian’s Rosemary Neill, Darrieussecq suggested that in All the Way her protagonist’s passivity was quite typical of 21st-century relationships. “I think that in spite of our feminist efforts to raise our daughters as powerfully as our sons — and I have a son and two daughters — the daughters still grow up with Sleeping Beauty in their mind. In spite of our efforts … they still wait for a man. They wait for the prince, and their life will begin. It’s a pity. Even me, I have to fight against that.”

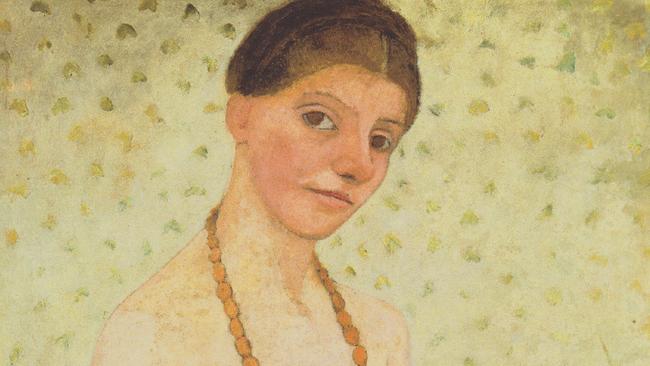

In her newest offering, Being Here, an allusive short memoir that reads like a novel, Darrieussecq traces the short but productive life of German expressionist painter Paula Modersohn-Becker, who was born in 1876 — not long before the dawn of an optimistic new century — and would be dead at 31. The artist’s outlook, which today would chime with a feminist’s position, may be what attracted Darrieussecq to her.

Paula Becker was attractive, quietly confident and organised in that northern Germanic way. Her best friend was Clara Westhoff, who would marry poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Soon after, Paula married painter Otto Modersohn. All four began as good friends but geographical distance and diverging experiences of the world saw this friendship falter.

Although Darrieussecq had access to the diaries of all four parties, and these are quoted skilfully, the reader is left wondering if it was Rilke Paula was waiting for, rather than Modersohn, who was, after all, married when she first met him.

Paula comes from a small village with the inelegant name of Worpswede, northeast of Bremen in Saxony. In a few deft impressionist strokes, Darrieussecq conjures a picture of the sleepy, regulated bucolic life that perfectly approximates those scenes from 19th-century European literature such as Theodore Fontaine’s Effi Briest and Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary — and from which Paula will need to escape from time to time.

This is from Otto’s journal: “Paula paints, reads, plays the piano etc. The household is also in very good hands — the only things lacking are her interest in the family and her relationship with the house.” And this, from Rilke writing to another young poet: “someday there will be girls and women whose name will no longer mean the mere opposite of the male, but something in itself … life and reality: the female human being”.

Paula had tasted Paris, having convinced her family to let her study there at the Academie Colarossi School in 1900 with a modest endowment from her uncle. She blossomed in that short visit and won a prize while noting that it is “harder for women”. They were expected to paint charming little paintings while the male students are allowed to “play the fool”.

Paula’s works are suffused with the modest routines of daily life. Melancholy village women and girls are painted with intensity and tenderness, and they all have an air of solemn detachment. As Darrieussecq points out: “Little girls learn soon enough that the world does not belong to them.”

She describes Paula’s painting technique: “layer after layer, a surface that is rough and alive, like old marble or sandstone that has been out in the air, exposed to the workings of weather and time”. Above all, Paula has painted the female nude — including herself — and pregnant. This fact alone accounts for much of her public profile, while it has never been central to placing a male painter on the map — except perhaps for Paul Gauguin.

She found a way to return to Paris, having missed its raw energy and colour. In 1905 she was on her way and Otto was anxious.

Darrieussecq implies that Paula’s warmth towards her husband seems more fully expressed when she has established some distance between them. The reader can sense her joy at being on her own, unencumbered by monotonous household routines, but dejection sets in. “She can’t get hold of potatoes anywhere: instead, it’s bread, always bread.” Nonetheless, she planned to remain there and told Otto she doesn’t want the marriage.

After a brief reconciliation she was pregnant. It was a difficult birth. Eighteen days later she fell to the floor and died of an embolism. Her last words? “Schade” (a pity). Paula Modersohn-Becker sold only three paintings in her lifetime, to family friends and to Rilke, but years later her work did not escape the attention of the Nazis, who denigrated it as part of the modernist Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) movement. Today there is a museum devoted to her in Bremen.

After Paula died, her friend Clara tried to grasp the substance of her paintings and suggested that the chasm between the description or interpretation and the fact of a painting might be unbridgeable.

Indeed, how often do we approach a painting today and realise that it has taken us to a place where words won’t follow?

Being Here: The Life of Paula Modersohn-Becker

By Marie Darrieussecq

Text, 154pp, $24.99

Patricia Anderson is an author and editor.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout