Creativity salvaged from the domestic

JUST in case the celebrated Thea Astley was getting uppity, formidable editor Clem Christesen was there to set her straight.

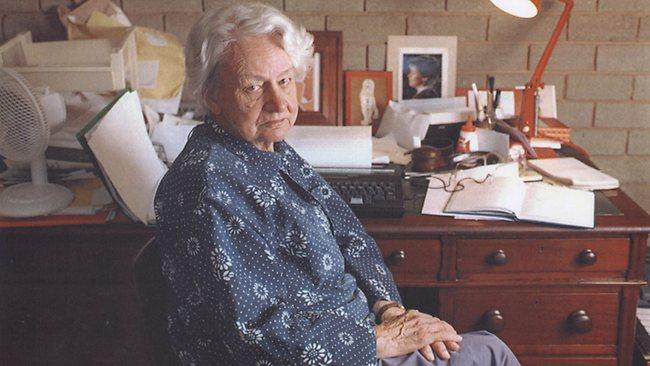

SHE had written four novels and won the Miles Franklin Literary Award twice, but just in case Thea Astley was getting uppity, formidable editor Clem Christesen was there to set her straight.

"Frankly I didn't feel your work to date warranted an essay -- it's not yet substantial enough," the Meanjin editor wrote to the 42-year-old writer in 1967. "Please don't be 'affronted' by these remarks: perhaps you too might concede that you haven't yet written a really significant novel."

Ah, those were the days, when real writers were blokes and women were counselled not to get upset when criticised. Then again, Astley seemed undaunted, like most of the nine female writers covered in this enjoyable book. Just as well. Nine Lives shows that while they do not play the gender card when they describe difficulties in their careers, their success lay largely in the hands of powerful male gatekeepers.

An adjunct professor in English and women's studies at Flinders University in Adelaide, Susan Sheridan has published extensively in cultural history. She has a sure sense of the era and the work of these women: Astley, Judith Wright, Dorothy Hewett, Gwen Harwood, Rosemary Dobson, Elizabeth Jolley, Jessica Anderson, Amy Witting and Dorothy Auchterlonie Green. The first seven are household names for Australians of a certain age. The final two are less known but their stories no less interesting for that.

Nine Lives focuses more on the production of the work -- the problems the women faced in finding time and space to write and in having work published -- rather than the work itself. Sheridan is interested in why and how their careers developed differently from those of men in the period from 1945 to the early 1970s when local literature flourished, thanks to commonwealth support, a burst of activity across the arts and magazines such as Quadrant, Overland and Australian Book Review.

These women caught the wave, but their experience was shaped by the prevailing norms around the role of women. All were from middle or upper-class families and were well-educated. All married and had children. They ran homes. Some, such as Wright, Green and Hewett, were the main breadwinners and some taught at school and university. But most, Sheridan notes, were not driven by the desire for a professional career. An earlier generation of women had tended to choose between "love and autonomy". These nine salvaged creativity from the domestic.

Sheridan avoids the more usual approach of feminist studies, in which "women in a patriarchal world have been characterised as rank outsiders, as lacking an authentic speech of their own, as eclipsed by male culture". Her analysis of the "varying degrees of recognition" these women achieved is more subtle.

The nine are considered in separate essays, a form that provides a succinct history of their careers. Sheridan is sound on biography and literary criticism but never loses sight of her goal of describing the process of publication and recognition, the point at which the writer intersects with the society. She is helped by a wealth of new material from the personal and professional letters of these writers. By looking at the editors who wielded the power, such as Christesen, she throws light on an extraordinary period of Australian literature.

The patterns are fascinating: how our poetry was privileged ahead of our fiction; how the gap between "serious" and "popular" literature began as universities included Australian work in their courses; how men and women alike were so committed to nurturing a distinctively antipodean culture in this period.

Some differences are intriguing. Take politics. Most of the women -- except young communist Hewett, and later in life, activist Wright -- were not overtly political although many held strong convictions. They stayed out of the raging Cold War debates that captured many of the men. "Their sense of the social responsibility of writers in most cases did not match that of their male contemporaries," Sheridan writes.

It's fascinating stuff: an important addition to the history of modern Australia that is very accessible to general readers.

Helen Trinca is a senior writer on The Australian.

Nine Lives: Postwar Women Writers Making Their Mark

By Susan Sheridan

UQP, 288pp, $34.95