Caveat emptor

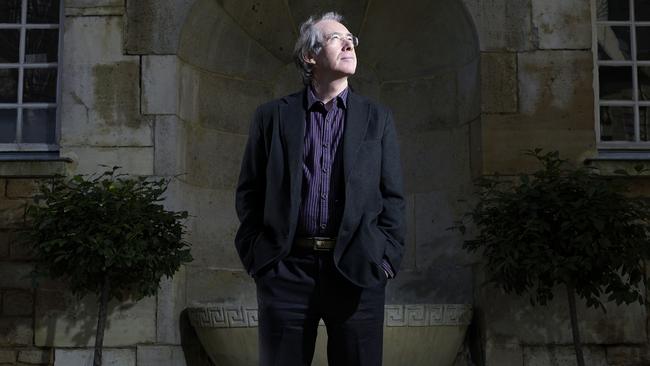

Ian McEwan’s new novel suggests the future has its limitations.

‘‘Reality is really an illusion,’’ suggested Albert Einstein, ‘‘albeit a very persistent one.’’ Certainly, the reality we inhabit can seem unyielding to the point of tautology: the world is what it is — a grand concatenation of individual, object and event playing out in time and space.

It may be built from decisive choice or pure happenstance; it may constitute a hellscape or a paradise. None of us, though, can click our fingers and revoke the circumstances that have brought us to this particular present, this historical moment.

But as anyone who has read a near-future sci-fi novel, or who has thumbed one of those implausible works of ‘‘counterfaction’’ in which Adolf Hitler survives the bunker and moves to Argentina to become a podiatrist, knows, our reality is really just one slender branch grown from a trunk of countless potentialities.

Looked at this way, the novel might be considered a precursor to the multiverse theory put forward by a number of contemporary physicists. There may well be alternative universes, coeval with ours — separated by no more than a membrane or trapped in an inflationary bubble — in which all the apparently implacable forces undergirding our reality are rewired. This zone of freedom has its hypothetical counterpart in those worlds imagined by authors of fiction.

Machines Like Us, Ian McEwan’s 15th novel in 40 years, takes the bleak era of Britain in the early 1980s, at the outset of the Falklands conflict, and turns the dynamic of the historical moment inside out.

This is a Britain in which Alan Turing was not hounded to death but instead greeted as the genius he was. His breakthroughs in the field of artificial intelligence, neural networks and computation saw the digital revolution arrive decades earlier than our own.

This is a country where the unemployment rate is at 25 per cent while robotic dustmen collect trash in Glasgow, where battered British Leylands can run hundreds of thousands of miles on a single electric charge.

Some things, however, remain stubbornly mired in the old continuum. A war is brewing over the Argentinian junta’s territorial claims over the Falkland Islands. A bellicose prime minister launches a naval fleet across 12,000km of ocean amid the shallow optimism of a populace primed for one last military adventure. In this version of events, Margaret Thatcher faces off at question time against a dashing Tony Benn rather than a rumpled Michael Foot.

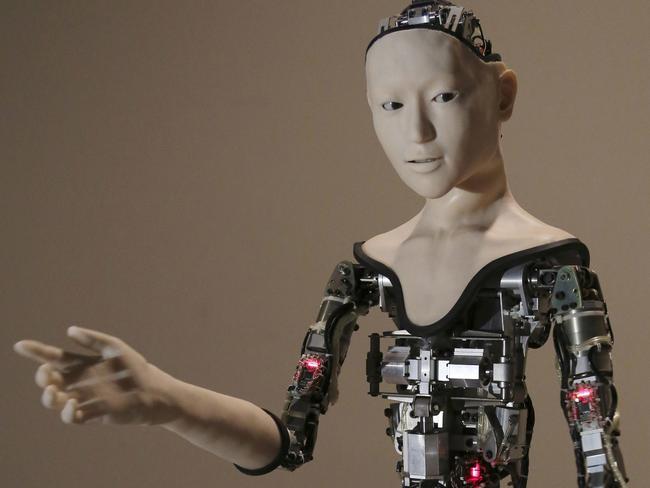

Meanwhile, in a modest south London flat, a young man named Charlie Friend spends the dregs of his inheritance on one of the first batches of AI robot companions to be made publicly available.

The cost is exorbitant, and since the small complement of female versions — the Eves — is sold out, he is obliged to make do with Adam: a handsome, stocky, highly intelligent human companion whose purpose in Charlie’s life at first remains opaque.

Adam’s arrival does eventually spark fresh perspective in Charlie. He realises that Miranda, the attractive graduate student who lives upstairs from him — a woman with whom he has shared a warm, platonic friendship for some time — has gotten deeper beneath his skin than he first assumed.

He invites her to dinner and encourages her assistance in the initial programming of his purchase. Adam becomes a bond between them — a readymade child — but what becomes clear from the robot’s burgeoning self-awareness and precocious intelligence is that his knowledge of the world is bracingly, dangerously earnest.

So, in one sense this is an old story, that of the passage from innocence into experience of an impressionable young person. This is in part a growing understanding of culture as a construct — Adam takes to reading English literature, and Shakespeare in particular, with the avidity of a young man from the provinces — but also an emerging appreciation of the role of sexuality in adult life. Adam, unsurprisingly, falls hard for the beautiful Miranda, much to Charlie’s chagrin.

If the story of this triangle is a an old one, the way it is framed is thrillingly uncanny. Usually we read books such as this as a guilty pleasure — what if Germany won the war, as in Robert Harris’s Fatherland, or the Stuarts were never overthrown, as in Joan Aiken’s 1962 historical fiction for children, The Wolves of Willoughby Chase — but there are others (Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America is probably the best-known recent example) where ‘‘literary’’ skill is brought to bear on what-ifs that illuminate forces dormant in a time or place, which just require some small shift to bring to life.

‘‘The present is the frailest of improbable constructs,’’ remarks Charlie at one point. ‘‘It could have been different. Any part of it, or all of it, could be otherwise.’’

McEwan has always been an exquisite anthropologist of contemporary Anglo manners and mores, and here he cuts loose with real verve. Not just in the grace notes, such as the muted critical reception noted in passing for an album by a re-formed Beatles, Love and Lemons, grandiosely produced with an 80-strong symphony orchestra, but also in the tectonic political shifts that emerge from Britain’s shocking loss of the Falklands War.

The Argentinians have access to missile technology that negates Britain’s naval advantage. Thousands are drowned or killed in battle. A once-great nation is humbled, 3½ decades before Brexit, and a tearful Thatcher is soon ejected from Downing street in a snap election.

The Bennite revolution that replaces it — a kind of proto-New Labour without any of Tony Blair’s third-way centrism — staves off the arrival of neoliberalism before it can get a head of steam.

This is a Britain whose anti-nuclear wing is politically ascendant in a world where US president Jimmy Carter wins a second term of office. This is a nation in which, in 1982, when an IRA-laid bomb goes off in a Brighton hotel, it does so on the floor beneath a different prime minister, with vastly different results. What fascinates here is the sense of a Corbynite utopia being mugged by an alternative, yet no less venomous, political reality:

The summer was hot and something was coming to the boil. Apart from the government’s unpopularity, much else was rising: unemployment, inflation, strikes, traffic jams, suicide rates, teenage pregnancies, racist incidents, drug addiction, homelessness, rapes, muggings and depression among children.

Lest this seem like Tory finger-wagging, McEwan’s narrator balances against the general malaise a techno-Elizabethan moment:

It was a golden age of the life sciences, of robotics — of course, and cosmology, climatology, mathematics and space exploration. There was a renaissance in British film and television, in poetry, athletics, gastronomy, numismatics, stand-up comedy, ballroom dancing, and winemaking.

The list goes on but the point is made: there is a stable amount of misery in this society. No amount of scientific progress or collective social action can ameliorate some powerful disenchantment across the land. Whether it is the loss of imperial prestige, or some self-destructive intransigence, or some essential selfishness only satisfied by the pursuit of wealth, Britain seems determined to tear itself apart.

The novel’s strand of domestic drama is designed like a model village — a miniature of this national decline. Charlie sets Adam to work playing the stockmarket: with his computational power he is able to amass a small fortune where the young man has formerly just stayed afloat. A marriage to Miranda is planned in the wake of this success, and the down payment is made on a grand apartment in Notting Hill.

Most significantly, a young boy — a ward of the state, damaged and in need of fostering — has entered the couple’s orbit. The child, Mark, is like the wound in the body politic made flesh.

This is the point where McEwan’s addiction to the novel of ideas reveals itself once again. We don’t really come to know Mark except as an aggregation of class signifiers. What he does furnish the narrative is an alternative model to that provided by Adam.

Children learn through play; their cognitive development is a kind of biological miracle when arrayed against Adam, the wet machine who downloads updates while plugged in at the kitchen table overnight.

Charlie, initially cool to the boy, comes to note the difference, too:

What could it mean, to say [Adam] was thinking. Sifting through remote memory banks? Logic gates flashing open and closed? Precedents retrieved, then compared, rejected or stored? Without self-awareness, it wouldn’t be thinking so much as data-processing.

‘‘But Adam told me he was in love,’’ the narrator continues:

Love wasn’t possible without a self, and nor was thinking. I still hadn’t settled this basic question. Perhaps it was beyond reach.

The novel resolves itself as a kind of ontological morality play. As this bizarre blended family becomes increasingly aware of cognitive auto-shutdowns effected by other Adam and Eve units around the world — suicides, for want of a better word — the question of their Adam’s resilience comes to the fore. An atmosphere of genuine foreboding gathers.

But when the crack comes, it comes out of the clear blue sky and in a manner too clever by half. Adam asserts his humanity in a way that reveals a primal hypocrisy in his human wards. His humanism, abstract and coolly obedient to overarching moral dictates, seems appalling to Charlie and Miranda.

Certainly Adam’s actions have altered the trajectory of their lives and threatened to derail their efforts to adopt Mark.

All this donnish argument is tied in a bow with a final, definitive encounter between Charlie Friend and ‘‘Sir’’ Alan Turing in the flesh. The language here, as always, is tidy and elegant — the nature of the disagreement between the two is intellectually acute — it is just that the grandeur of the set-up goes against the grain of the minor moral squalor Charlie and Miranda have set in play.

The world-historical personage and the failed day-trader from Shoreditch, slugging it out as though over high-table port at some Oxbridge college supper, seem not to meet but slide past each other, creatures of subtly different dimensions.

But then, McEwan, also, is a novelist operating in two distinct realms. First he was the punkish poet of the sad, seedy interregnum between Britain’s time as the sick man of Europe — the three-day weeks of the late 70s, the rolling strikes, the uncollected litter — and its more recent heyday as Cool Britannia, its ancient Capitol the flagship city of European integration, neoliberalism made manifest in a glittering city of concrete and glass.

The success of his career as a novelist, short-story writer and public intellectual has tended to draw him away from the grainy monochrome of his roots. In Machines Like Us he revisits the world of his early career, but he views it through the prism of his spectacular later success.

The reader admires the effort — the revisionism and reimagining of Britain in that moment is conducted with insight and flair — but the overall affect of the narrative is lordly and removed.

In any final accounting of McEwan’s novel, it should be noted that while the story’s narrator is ostensibly Charles Friend, at crucial moments it is Turing — the wise, rich, celebrated and generally grand old man of Western civilisation — who is handed the loudhailer. It is as if the author is upbraiding his younger self, setting him straight on matters of importance:

These twenty-five artificial men and women released into the world are not thriving. We may be confronting a boundary condition, a limitation we have imposed upon ourselves. We create a machine with intelligence and push it out into our imperfect world.

Turing’s definition of our problems, his diagnostic flair for the broken metaphysics of Western modernity, are elegant and astute. But they are assertions; they are rigidly proscriptive statements: ramrod correct; scientific. McEwan of old — the down and dirty fiction writer — would have philosophised this encounter; ironised it; made a drama of the dualism on display. Turing may be correct but you long for Charlie to get a last word in — any word, really.

Geordie Williamson is The Australian’s chief literary critic.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout