Black and white testament to era

The country town of Deane, the setting of Tony Birch’s new novel, is vividly rendered for a place that does not really exist.

Torpid beneath an inevitable sun, its dray-wide streets a study in shadow and glare, the country town of Deane — primary setting of Tony Birch’s new novel The White Girl, his fourth in a dozen years — is vividly rendered for a place that does not really exist. This is probably because some version of it has sprung up in so many parts of this country that only a generic instance is big enough to contain them all.

Many readers, then, will be familiar with the mid-20th century template. An inland river town built on agriculture and mining, just starting to feel the first hints of postwar decline. Deane’s picture theatre closed two years back, about the time televisions first appeared in store windows at the regional centre, 40 miles away. Mounting diversions from the river for farming purposes have begun to affect the body of water. Its flow — and so the region’s broader ecology — has begun to stutter.

And the old racial certitudes that drew a colour bar through town like a ruler, granting the local constabulary powers of association and movement over the few remaining indigenous locals and their children, much as the religious missions that raised the older generation once possessed? They are beginning to stutter, too.

In the cities, political and social ferment has begun to sweat beneath the crisply ironed pieties of the Menzies era. All those minorities, from European migrants to working women, whose existence has been seen by some as a threat to the established order, have begun changing society by dint of merely existing, by being woven into the fabric of a changing nation.

Odette Brown knows nothing of this. She has barely left the town of Deane since she arrived as a child, growing up the daughter of a smart and able Aboriginal man who was later killed in an accident at the local quarry. She spent most of her days in service to white households: the once-prosperous farmers of the district, a number of them now fallen on harder times.

All these years later Odette still lives in one of the old quarry shacks, an old woman alone aside from her granddaughter, Cecily, otherwise known as Sissy. The pair live a quiet, isolated existence, subsistence-level in some respects — a bath once a week in an outdoor tub; their only income arriving in the form of postal orders from the white woman who commissions gift card artworks from Odette — but richly loving and companionable.

The missing link here is Sissy’s mother, Lila. It seems likely from the evidence readers are given that Lila was raped by a local white man when she was a teen. Sissy was the resulting issue: a white girl, almost, hence the novel’s title. Odette lost Lila to the wider world when Sissy was still a baby, with only a few letters to crumb her trail in the years since. The narrative’s opening finds the two left-behinds bound the more tightly by that essential loss.

Birch’s vision of country Australia in this period is Bakelite-smooth. His is a quiet, steady and unerring sense of time and place. Everything that needs to be present, from the jam tins in which Odette keeps her earnings — since, as an Aboriginal woman, she is not permitted to have a bank account of her own — to the bread-and-dripping fry-up that she treats herself each Sunday morning (in mixed memory of her mission upbringing), resonates with pure ordinariness. Birch intuits that cultural memory migrates into objects over time and he curates them deftly in establishing the scene.

But it is the spare cast of town characters that move the story forward; Henry Lamb, for example, with his ancient sweat-stained Akubra and beloved canine companion Rowdy.

As a child Henry suffered a head injury that kicked all but some mechanical genius and a deal of fundamental kindness out of him. The butt of jokes and pranks for generations of young men in the town, he has true sympathy for Odette and does what he can to help the pair.

Or chain-smoking, plain-speaking Millie Khan, lifelong friend of Odette, married to the descendant of Afghan cameleers. She lives in a former saddlery slowly being swallowed by a dry billabong, determined always to assert independence from a society that sees a black woman married to a Muslim as a double affront.

Birch balances this skeleton staff of small-town decency against some moral invertebrates — such as Bill Shea, the outgoing local constable, an ineffectual drunk — and some true-blue monsters. The Kane family, pere et fils, are failed farmers whose bitterness towards the world is now directed against those, such as Odette and Henry, who remain among the few they can look down upon.

Odette worked for the family, back in the day. She witnessed the violence Joe Kane meted out to his sons, turning one, George, into a victim and the other, Aaron, into a sadist. When Odette discovers that Aaron has begun to take an interest in Sissy, she fears a repeat of past injuries. Despite feeling the weight of the years and some ominous new pains, the doughty old woman steels herself for one more fight.

What Odette has reckoned on is the possibility that the worst person in town may not bear the Kane surname. Newly arrived police Sergeant Lowe is cold and ruthless, curdled with pathologies. He spent the postwar years in Europe, ostensibly assisting with displaced persons but, the novel creepily infers, mainly using his power to manipulate and hurt the innocent.

In other words, he is a creature perfectly designed to work for an authority that claims all indigenous children in the state as its wards. Lowe draws up a list of young people in the township who may require his “guardianship” and it is the knowledge that this man is after her granddaughter that inspires Odette’s most desperate move: to flee the town for the city, in frail hopes of finding Lila and passing Sissy back into her care.

Birch brings us to this point with minimal fuss, but the temperature of the story soon rises. For all the author’s limpid grace as a prose writer, his calm can disguise a mean rhetorical uppercut. When Lowe discovers that the pair have absconded despite his directives to remain, he is furious. Rounding on Milly Khan on the street, he lets rip:

“The Child, Cecily, must be returned to Deane, for her own Welfare.”

“Welfare?” Milly replies incredulously. “Oh, you’ve looked after the welfare of our young girls for a long time now. Most of them are dead, disappeared, or were sent mad by what you did to them in the institutions. That’s not welfare, Sergeant. I think your own law would call that murder.”

Note how starkly black and white is delineated here. It almost begs some “what ifs”. What if Sergeant Lowe spoke not as a monster — what if his cold authoritarianism came out of a sincere if misplaced belief that what he was doing was kind? What if Millie Kahn were not a statue of rectitude but a woman who had internalised some guilt or uncertainty in relation to these same “young girls”?

It is possible, as a reader, to thrill to righteousness while feeling aesthetically short-changed: and this, for all is virtues, can sometimes be the experience when reading The White Girl. The characters are shunted to their allotted places like sheep being run through a drafting race.

The local doctor in Deane who examines Milly is a Jewish Holocaust survivor. He’s good. The spinster daughter of local graziers encountered on the train to the city is bad. The presumably gay bureaucrat who works to furnish Odette with freedom of movement documents is good. The lecherous, form-guide brandishing owner of the cafe where Lila used to work is bad.

It is fair to observe, of course, that a man who has suffered the horror of the death camps is likelier to stand up for outcasts elsewhere. It is also only appropriate that someone obliged to disguise their sexual orientation would have sympathy for an old woman attempting to help her daughter temporarily pass as white to save her.

The responsibility of the author is not, however, simply to switch easy binaries, so that old Menzies-era convictions are replaced by a rainbow parade of contemporary merits. It is to explode the assumption that we creatures are so easily tagged in the first place. That said, to whom is the author ultimately responsible? Returning to this fiction of uncommon moral simplicity, it is worth asking whether Birch might have made certain decisions in the writing of The White Girl that had nothing to do with tweaking the palates of those belonging to what Nicolas Rothwell once called “the reading classes”.

The sincerity and clarity of this novelmay mean some smoothing where wrinkles are required. But as a testament to the real calamities that befell generations of indigenous Australians as a direct result of white paternalism and bunk racial ideology — as a record of the pain and hurt suffered, and of the immense bravery and care shown by so many women in communities such as Deane — the novel rings clear as a bell.

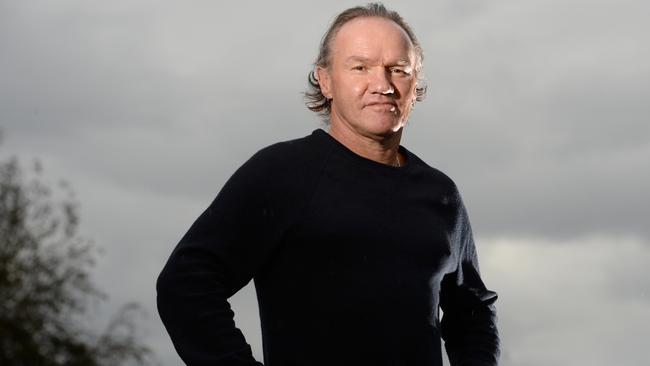

Geordie Williamson is The Australian’s chief literary critic.

The White Girl

By Tony Birch. UQP, 272pp, $29.95

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout