Beautiful and clumsy

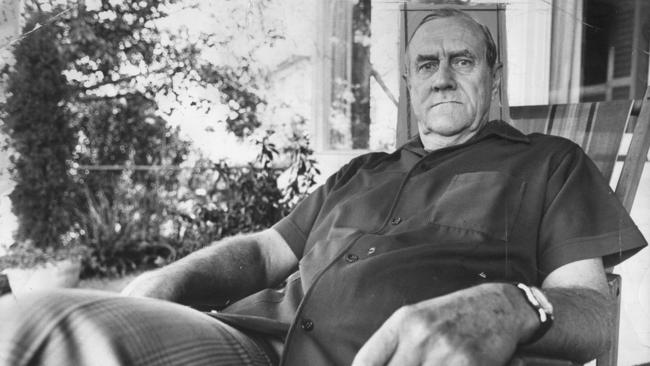

Patrick White exposed and confronted the shaping pathologies of life.

“So dry were the early months of 1973 that flocks of sulphur-crested cockatoos flew in from the bush to plunder city gardens. When they first appeared on the lawn outside his window

White stopped typing …”

-

Why did Patrick White stop typing? David Marr’s 1991 biography of White, quoted above, records the inauguration of an idea and a title, but also a moment of imaginative interception. The scruffy birds, raucous and unruly, arrived in White’s Sydney garden with the authority of an idea.

Interception, auspice, the command or address of the creaturely world; these were all carried by wings into the writer’s backyard. Six, then 12, then 14 birds arrived, fed daily on sunflower seeds by White’s partner, Manoly Lascaris.

This arrival was confirmed by symbol and coincidence. On the day White finished the manuscript of his collection of six stories, David Campbell’s poem Cockatoos arrived in the post as a gift.

By his own admission, White adored coincidence, and was not afraid to employ it in his various fictions. So perhaps his own Cockatoos seemed blessed by presence itself, by an incarnation of the originating idea.

This was the year White published The Eye of the Storm and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. He was described in the Nobel citation as ‘‘the one who, for the first time, has given the continent of Australia an authentic voice that carries across the world’’.

This commendation fails to acknowledge the audacity of White’s work, that quality that made it not an exemplar of national spirit or ‘‘authenticity’’ so much as the singular project of someone for whom art offered questions, not answers, and an anguishing search for resolution in the irresolute business of being.

Nor did the citation mention the bodily aspect of White’s work: that he explores disgust, shame, disgrace and perversion; that he delights in the joys and insurrections of the flesh. His characters are all emphatically embodied: they fart, spit and suck at their teeth; they enjoy an easy piss or the grim success of a cool stool; they are frequently lustful (and frequently repressed); they are incestuous, adulterous, grumpy and venal.

Interception and incarnation: what does it mean, in this fallen state, to be visited by something madly beautiful? The epigraph of The Eye of the Storm is a line from a short story by Yasunari Kawabata: He felt what could have been a tremor of heaven’s own perverse love. Its conditional mood, the sensation it describes and the specificity of the adjective together epitomise what by then had become central preoccupations for White.

Love, feeling and perversity govern his work of this period. At the end of White’s first great novel, The Tree of Man (1956), Stan Parker, the humble protagonist, finds himself sitting in his back garden in a circle with no centre or circumference; he spits on the ground and sees God in his gob of spittle.

There’s religious orthodoxy here but also heretical glee. There’s a wish to concede the material self, and to relate the mess and muck of the human body to moments of grace. This incident is cited in debates over immanence and transcendence in White’s work, but what is consistent is his attempt to produce a sensual theology. Stan Parker is dying, cranky, exhausted by his labouring life, but he is also shyly aware of mystery. He is inhabiting, all alone, a ‘‘large triumphal scheme’’. White’s characters often experience spiritual intensification; and it is this difficult linking of the ordinary and extraordinary, the tremors from heaven and the embarrassing and vulnerable body, that his unusual prose style strives to express.

So what of The Cockatoos? Wonderfully broad in setting — the stories take place in Sicily, Greece, Egypt and Australia — they are also typical of White’s fiction in their combination of social comedy, inner quest and revelations of deep wounding. All engage modernist effects and concern melancholy and suffering. And, as in all White’s work, remarkable insights arise from his complicated humanism.

He pays particular attention in this volume to the solidarity of married life, to those forms of tenderness, reticence and insecurity, often unregarded, sometimes neurotic, that shape the complex ways in which people live together over time. Most of the protagonists are older married or retired couples and there’s an end-of-life searching, a quest for meaning after work, that gives a poignancy to what often begin as comic tales. There’s also a theme of same-sex desire: White insists that desire must be owned and expressed. The thwarting of desire breeds despair and monstrosity.

The opening story, A Woman’s Hand, tells of Evelyn and Harold Fazackerley, who endure a dull retirement by incessant touring, culminating, with disappointment, at the Dead Heart. It begins as comedic, with a description of ‘‘Lovely Homes worth breaking into’’ that sit perched on a windy cliff on Sydney’s south coast:

To view the view might have been their confessable intention, but they had ended, seemingly, overwhelmed by it. Or bored. The owners of the lovely seaside homes sat in their worldly cells playing bridge, licking the chocolate off their fingers, in one case copulating, on pink chenille, on the master bed.It’s witty, but not cruel, taking as the object of satire a vulgar-materialist version of Australianness as currency. ‘‘In the long run,’’ Evelyn says, ‘‘Australian nationality paid.’’ Centred mostly on her point of view, the story tracks the malevolence of Evelyn’s smug and complacent sense of possession.

She arranges a match between two acquaintances, a man she intuits is queer (her word) and a woman she considers a lesbian. Unable to endure their difference, she wishes ignorantly to destroy both.

Underlying this story is a plea for tolerance and autonomy. The queer man, Clem, lives in a shack that invites Evelyn’s contempt and has a past in which he reads Cavafy, has an Egyptian male companion and survives an unspeakable ‘‘breakdown’’. The woman, Nesta, is marked by her own radical particularity.

A Woman’s Hand shifts to Harold in its closing pages. After stumbling through the mists of the Blue Mountains into the scrub, he reaches the edge of a deep gorge and experiences himself, surrealistically, as one with his surroundings. He is the black water trickling at the bottom of the gorge, the cliffside ‘‘pocked with hidden caves’’.

He is reckoning with a failure to love, which might include a lost opportunity at intimacy with Clem, or with the elemental world, or indeed Evelyn herself. The story concludes brilliantly with the tragedy of ‘‘faces never touched’’.

The move to spiritual agony at the end of A Woman’s Hand is the typical trajectory of a White story. He negotiates the sacred and the profane in many registers, sometimes explicitly religious, as in The Full Belly. This short tale is set in Greece during the German occupation, and concerns the visions and torments of day-to-day starvation.

Four stories in White’s earlier volume The Burnt Ones (1964) considered ‘‘Mediterranean’’ are generally underrated. Allegorical in tone, they also have a stringent commitment to imagining the origin and life of White’s partner, Lascaris, who, like the young protagonist of this story, Costa, was a gifted and indulged boy, raised by two maiden aunts.

White turns here to his own love of Byzantine motifs. Costa is assailed in the madness of hunger by a visionary Panayia, the eastern Mary, and the lurid distortion of holy icons. His starving family, abject and humiliated, is set against the ‘‘professionally hungry’’ saints who stare from the iconostasis in the Church of the Annunciation.

Costa is tempted to prostitute himself for a tin of German meat but misses his chance, then returns to his home to desecrate the deathbed of his scholar aunt, Maro, who refuses to take nourishment. The climax of this story is appallingly vivid and Costa, once full of promise as a concert pianist, experiences metaphysical emptiness. His shame is overwhelming; he will never be full.

Sicilian Vespers oddly links these two stories. It’s another narrative of retirement: Ivy and Charles are Australians also touring and searching. In Palermo they meet Clark and Imelda Shacklock, wealthy American retirees. The retired couples in this collection are all childless or have lost a child, and their wandering state and enforced time together arouse retrospection and judgment.

A prudish but kindly couple, the Australians are educated and middle class, and have chosen to stay at the Hotel Gattopardo. References to Lampedusa are a shared joke in the story, just as Imelda’s reading matter, Manzoni’s The Betrothed, ironically accentuates the weakness of her own marriage.

The Shacklocks have founded their own art museum and own a Goya. But again White is interested less in the ideological claims of high art than in the address of the body, its temptations and embarrassments, and how these might illuminate his philosophical concern with incarnation and interception.

When Charles is laid low in his hotel room with a toothache, Ivy sets out on a twilight excursion with Clark during which, seized by confusion, she commits loveless and deeply unsatisfying adultery in a chapel: ‘‘Like two landed fish, they were lunging together, snout bruising snout …’’

This episode is described as blasphemy, and confirmed by ‘‘a loathing returned out of childhood’’, a vision of a cockroach flying from a meat safe and hitting her in the face. Ivy sees the Italian version — scarafaggio! — which she grinds underfoot and smears into the marble floor.

The story is remarkable in its balance of disgust and sympathy, and its negotiation of different orders of moral and aesthetic experience. Sicilian Vespers refers of course to the prayer service at evening (and Clark reminds us that no ‘‘communication’’, no communion, happens at this time) but also to the historical revolt in Palermo in 1282 against the rule of the French king, Charles of Anjou.

White would also have known that it was the title of an opera by Giuseppe Verdi. There’s a layered cultural soundtrack, but this is less compelling, finally, than the gentle denouement, the reconciliation in tender marital gestures and shared understandings. This is where White’s originality lies. He allows for extravagance and grotesquerie alongside touching circumspection. He admits moral failure while honouring small acts of communion.

The companion version of this story is Five-Twenty. A retired couple, Ella and Royal, sit every day on their porch on stinky Parramatta Road and watch the stream of rush hour cars as their form of joint entertainment.

They become obsessed with a particular car, a pink and beige Holden, that passes each day at 5.20pm. The Holden is an odd visitation, redolent of kitsch and in White’s aesthetic an index of spiritual corruption. Always seen in profile, the car and its occupant set up the rhythm of the couple’s meagre and diminished life.

Eventually Ella encounters the 5.20pm man in a predictably unsatisfactory and tragic meeting. There is a garden, there are car accidents and there is an insistence, once again, that inhabiting the shape of marriage but failing to love is an irredeemable tragedy.

One story in this volume, The Night the Prowler, now seems somewhat ill-conceived. Ironically, this is the best known of White’s short stories since it was made into a film in 1978, directed by Jim Sharman and for which White wrote the screenplay.

The story swings between domestic comedy and extravagant spiritual misery. It is set in a grand house near Centennial Park in Sydney (the location of White’s own home) and is bent on satirising middle-class repression.

At the same time, it centres on rape fantasies and a psychology of women’s desire that is unconvincing, if not offensive.

Finding a man in her bed, young Felicity stages her own violation and uses the incident to justify a suburban rebellion in which she breaks into and defiles the ‘‘lovely homes’’ of her neighbours.

The prose is gaudy and overexplicit: Felicity wishes ‘‘to destroy perhaps in one violent burst the nothing she was, to live, to be, to know’’. The park at night is a symbolic place of both degradation and liberation, and here White’s prose strains to express Felicity’s rage.

Celebrated in adaptation, this is the false note of the volume, a story contrived to shock, presumptuously sure of its crude suggestion that sexual violence frees and unrepresses.

The title story, The Cockatoos, returns to the mystery of visitation, this time told as suburban melodrama. The retired couple Mick and Olive Davoren have not spoken to each other for seven years, since Olive convinced herself that Mick let her budgerigar die. They inhabit different parts of the house and seldom communicate, and then only by writing.

There are fine comic touches but there’s also a sense of repetition and exhaustion. Adultery, suburban gardens, childlessness, inconsistently valued high art (in this case Mozart’s Don Giovanni), the awakening of memories that make it obvious a marriage has gone dry; these themes mix with jokes about burnt chops and an emphatic symbolic meaning.

The cockatoos are both numinous and vicious, their sulphur crests described as flicking open like a many-bladed knife, but also kindly, with ‘‘currant-eyes’’ and crests resembling ladies’ fans.

There’s nothing to match the imagistic reach of David Campbell’s simple: “But tongued like snow, if snow could cry / The cockatoos flake from the sky.’’ By the end of the story White’s birds have lost their mystical quality. Yet they compel relentless observation until the final event, in which the local undertaker brings a shotgun to disperse them.

The dispersal is watched by nine-year-old Tim Goodenough, driven by what he witnesses to his own rebellion at night in Centennial Park, where he meets the same cast of deros, predators and visions of drowned corpses that Felicity met in The Night the Prowler. He commits his own atrocity, and ends damaged and silent.

Eudora Welty, another tough, existential writer, shrewdly assessed the spirit of these stories: “ … they go off like cannons fired over some popular, scenic river — depth charges to bring up the drowned bodies. Accidentally set free by some catastrophe, general or personal — war, starvation, or nothing more than a husband’s toothache — Patrick White’s characters come to a point of discovery. It might be, for instance, that in overcoming repugnancies they are actually yielding to some far deeper attraction; the possibilities of a life have been those very things once felt as its dangers. Or they may learn, in confronting moral weakness in others, some flaw in themselves they’ve never suspected, still more terrifying.’’

This seems a wise assessment. The strengths of White are exemplified in this collection: the stories are excursive in feeling, full of brave intimations, cheeky wit and bold experiments in style. The shaping pathologies of life are exposed and confronted; weird epiphanies and peculiar characters are scrupulously notated.

‘‘A wave of white cockatoos is the most beautiful, clumsy sight,’’ White wrote to David Campbell.

This linking of beauty and clumsiness is typical of White’s sensibility. He wishes to discover in ordinary and vulgar experience the possibility of mystical interruption. And while stories don’t have the space of novels fully to develop character, White still manages to show the tormenting specificity of inner lives. There’s no comparison in Australian letters, no one else so brashly intense, so insistent on emotional wreckage and so finally inconsolable.

This is an edited extract from Gail Jones’s introduction to the Text Classics edition of The Cockatoos, by Patrick White (308pp, $12.95).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout