Beachcomber’s escape to paradise

The works in this delightful exhibition are presented without a single false note.

IT was late in September 1897 when the prototypical beachcomber, Edmund Banfield, arrived to settle for good on low-slung Dunk Island, a lush paradise off Mission Beach, far up north Queensland’s tropical coast. He was tubercular, on the verge of nervous collapse, partially blind, and he had a palsied hand; and with him came his deaf wife.

Hard initial circumstances - but Banfield stayed and thrived. The interweaving vistas of sky and reef and land and sea became his world: he made them famous in his first best-seller, The Confessions of a Beachcomber, and thus became the inspiration for a long and distinguished series of artistic pilgrims bound north in his wake.

Dunk, and nearby Bedarra and Timana, the three “Family Islands”, were the focus of a sustained mid-20th century provincial Bohemia that endured for several generations: sculptors, painters and tapestry artists all gathered there.

To the Islands, a subtle, small-scale exhibition, first staged at Townsville’s Perc Tucker Regional Gallery and now on view in Cairns, presents their works and tells their tale.

It is that rare thing: a public gallery show that reconceives its subject and brings a fresh distinction to its cast of characters. As curator Ross Searle argues, the reputation of these island artists as pioneers of Australian painting is underdone - and the problem is general. “There continues to be a wholesale lack of recognition of the contribution of regional artists to the overall canon of Australian art history,” he says.

Regional galleries such as those of Townsville and Cairns have a clear mandate to redress this neglect, and this show is a vital advance. The three islands are the unifying theme and key subjects: they are firmly placed at its centre - their look, their light, the striking colours they suggest to the eye.

It is an unusual tale, and it begins with a most unusual artist, Noel Wood, now, like Banfield, largely forgotten, despite the vast fame he enjoyed at the mid-point of his long career. Wood came north from Melbourne with his young family in 1936, fresh from a viewing of Ian Fairweather’s works on paper, his head full of modernist ideas. He chose Bedarra Island as his place of refuge: he struggled there, living on a diet of oysters and coconuts. His mood revived when he shifted across to Dunk, and began haunting Banfield’s old tropical gardens and the beachcomber’s rundown shack on Brammo Bay. Wood’s work came together: he caught the bright green of the jungle and the red of the island soil; he became a recorder of clouds and sky, and of shadows and the gleam of sun on palm and vine.

He sent his work south, and it was rapturously received. In depression-era Melbourne, his vivid images of tropical landscape seemed like dreams of a perfect life, and he was soon one of the most widely recognised artists of his day. Reviewers dwelled not on his methods or the influences in his works, but their exoticism: “Mr Wood rejoices in the lush colour of it all - the hard blue shadows, the pale green and the dark green, the flat grey of a bay under a rain shower.”

A landmark exhibition was held in Brisbane in late 1940: according to The Courier-Mail critic, this was the first time paintings from the far north had been shown in the capital. The Queensland Art Gallery bought one of Wood’s most resolved and emblematic pieces, The path to Banfield’s old home. It is a scene of glaring sunlight and stark shadow contrasts, the contours of the landscape picked out by the red slash of the dirt track that bisects the work.

Other artists soon followed Wood’s lead. The first was Valerie Albiston, who travelled “as far north as possible” in flight from an unhappy love affair, and stumbled on Timana Island, owned at that time by Dr Bernardo’s homes. It was a change from Elwood, Melbourne. She contacted her sister, Yvonne Cohen, who joined her: the two had a shack built on the island’s sheltered shore and set to work. Their paintings, small in scale, have an immediacy and a tone of sheer responsiveness to nature that rarely surfaces in the works Wood made over the same time in the same island world.

The sisters had company: there was Charlie, an Aboriginal Malay who lived on Dunk Island and worked as a roustabout - he guided them through the rainforest, showing them its range of medicines and healing plants. And there was Nugget, a beachcomber from Dunk who moved to Timana and helped out. He was a literateur: indeed, “books were his only link to the affluent family he had discarded in his youth”.

Other artists were drawn to the group. One was a painter named Charlie Martin, who knew Fairweather. Through this connection Fairweather stayed on Bedarra before embarking on the journey that took him to Darwin, and eventually by raft to the Indonesian archipelago. He gave to Martin all the works he had painted and sketchbooks he had filled during his stay: he had no further use for them. Martin promptly burned the sketchbooks, and wrote to Valerie Albiston, asking if he should burn the canvases, too. She intervened. The paintings were dispersed among the Islands circle. They paid what seemed like the going rate: top price about £20.

When war came, life on Dunk, Bedarra and Timana tightened up. The islands were declared a military zone and movements were controlled. The sisters went on painting, dividing their lives between Elwood and the tropics. One can see a progress through the years in the works they made, which form the backbone of this exhibition: simple Fauvist colour seems to darken into more saturated Cezanne hues.

A biographical catalogue note by Melbourne art historian and gallerist Catherine Stocky argues the island paintings of the two sisters “often had a spiritual, dreamy dimension to them and invoke the restfulness and utter beauty of their surroundings”. And this is true of many, but by no means all, of the works on view. Some are sombre, and the island landscapes can at times convey oppressive emotions or seem full of mystery, to the point where sea and sky dissolve and are replaced by abstract planes of light. Into the Blue, the most striking piece in To the Islands, a vortex maelstrom from the brush of Yvonne Cohen, reflects just such a vision and its attendant states of mind and heart.

Wartime over, mainstream Australia turned its attention to the Queensland tropics. Tourist boats appeared, the heyday of the sporting, sailing life dawned. Isolation on the Family Islands was no more. Other artists moved in: a new generation imbibed tropical colours and formed their own responses to the intensities of the coast. Tapestry artist Deanna Conti and her partner Bruce Arthur reached Timana in 1965 and set up a workshop: multiple studios flourished, and woven artworks from the islands enjoyed a vogue. It was 1973 when Fred Williams came north, on a journey that marked the last stage in his evolution as a painter, and seems the natural culmination of his experiments in adapting Western art to Australian patterning and light.

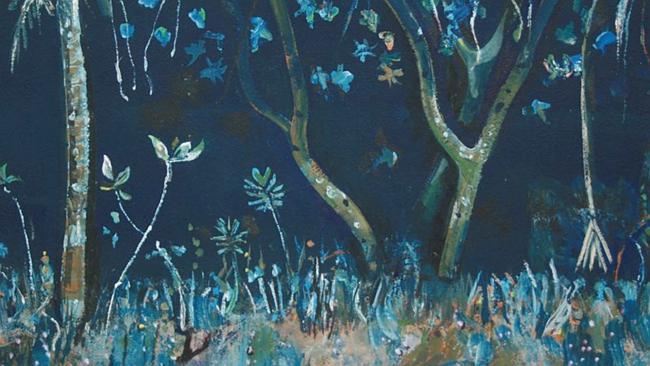

Williams had come to know, and paint, the Glasshouse Mountains region north of Brisbane through Albert Tucker: he eventually probed further north, and made two visits to Bedarra and Timana, and the work he produced there shows a keen focus on the specifics of the coastal landscape: flowers, tendrils, the “dark, tangled rainforest on the islands”.

Colour was all in these pieces: deep colours replaced the muted shades in his works depicting bleached-out southern country. Williams painted outdoors on the islands, using gouache. As Searle writes in his catalogue note: “Going to Queensland offered the ideal opportunity to make an abrupt change; and he was excited by the challenges of switching his palette to new rich colours.”

In truth, the islands were a way-stage on a protracted journey north, which led Williams to Weipa and the coastline of western Cape York, where in 1977 he was forcibly struck by the flat landscape and the views of sky and sea and bushfire plumes rising in still air. This trip resulted in a series of about 50 gouache works produced in his studio late that year. For Searle, these are among his most inventive compositions: “No doubt the environment of the islands was to shape and influence him in ways no other location in his long artistic career had before.” The artist’s widow, Lynn Williams, donated a striking gouache triad of pitcher-plant studies from the Weipa shoreline to the Perc Tucker Gallery in 2000: together with a deep-blue jungle scene made in the course of the 1973 Bedarra trip, it forms the natural climax of this exhibition, and is its closing highlight.

The islands off Mission Beach are transformed, of course, today: Dunk is a resort. The Family group lies in a marine national park, set within a reef landscape familiar, rather than remote. To the Islands captures a stretch of time when the Australian tropics were being explored and excavated in paint, and revealed to Western eyes. None of the artists whose works it brings together imposed themselves on the landscape they came into.

They were attentive, they were its students. They are well-served by this delightful exhibition, which has been conceived, mounted and displayed with exquisite tact. The works are modest records of an encounter: they are presented here for what they are, without a single false note in the ensemble.

Many regional gallery exhibition programs struggle for relevance, but Cairns and Townsville have their great themes, which have guided the landmark shows in both cities over the past two decades: the northern landscape, the “tropics” and their impact on the imagination and the eye.

To the Islands is at the Cairns Regional Gallery until March 9.