Art Gallery of NSW walls help to tell the story of Australia’s journey

THE Anglo-European tradition of painting in Australia yields a fascinating picture of existence in the New World.

TO walk into the glorious high-vaulted centre court of the Art Gallery of NSW’s old wing today and see the masterpieces of Australian life and landscape, hanging together inside the building foreshadowed for construction as they were actually being painted, is one of the great experiences of Australian art.

Step outside and walk north alongside warm sandstone walls towards Woolloomooloo, look across the water to where Charles Conder’s subject, the SS Orient, once plied its way to and from Europe, then gaze eastward where Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton ensconced themselves at Curlew Camp on the shore of Little Sirius Cove. Synergy of place, institutional patronage and creative moment in the lives of these artists is unmatched.

The Anglo-European tradition of painting in Australia yields a fascinating picture of existence in the New World. Australian art museums and libraries have accumulated most of the finest examples that reflect the story of a nation as it gradually emerged from a convict settlement in the late 18th century, flourishing in confidence with the Heidelberg School by the end of the 19th, then inflected through and beyond modernism to the 21st, when hesitancy and hope began to coalesce again, just as they had done two centuries earlier. One thing is certain: Australia has been a fertile source for the visual imagination of its original and new inhabitants in all its diverse moods.

The Art Gallery of NSW, established in 1871, has its own version of this story, sprinkled with many of the most admired masterpieces of Australian art. I was their custodian for 33 years prior to my retirement in 2012. A journey through 100 of my favourite artworks, from John Glover’s Natives on the Ouse River, Van Diemen’s Land of 1838 to Ben Quilty’s Fairy Bower Rorschach (2012) — bookended at either extremity with a shimmering light masking a theme of persecution — reveals how prescient the gallery has been in securing such pivotal works that tell us about our history, even the unpalatable, and the imaginative reach of our best artists.

But there is another theme: the importance of public funding and private benefaction towards the preservation of a sense of continuity. For this journey also illuminates the portrait of a public collection and its ongoing mission, looking back and forward in time, to enrich the national estate.

For instance, Glover’s melancholy image of the Big River clan in Tasmania, acquired through support from the Bain family in 1985, followed on from the gallery’s collecting catch-up policy, begun in the late 1960s when, upon approaching the opening of the new Captain Cook Wing in 1972, it was realised it had a deficient representation of early colonial art. One key painting purchased at that time was Eugene von Guerard’s Waterfall, Strath Creek 1862. This symmetrical Germanic view of nature in one fell swoop communicated the northern romantic notion that God might be sought in the cathedrals of the forest, even in Australia. Its influence on our artists of the modern era cannot be overestimated.

But while the gallery may have been lacking in colonial works for a period, its first trustees were determined to showcase practitioners of the time. The result of this approach was truly spectacular, for which we may give large credit to Julian Ashton, who became a trustee in 1889.

In 1888 the gallery had acquired Conder’s Departure of the Orient — Circular Quay, as well as a couple of watercolours by Ashton. This sale enabled Conder to go down to Melbourne and join the impressionists’ painting camps. Ashton then pushed for a sequence of momentous purchases: including Arthur Streeton’s Still glides the stream and shall forever glide (1890) and Fire’s on (Lapstone Tunnel), 1891; Tom Roberts’s The Golden Fleece (1894); and Frederick McCubbin’s On the wallaby track (1896).

We also find in the gallery’s centre court a climactic acquisition for the end of the century, George Lambert’s Across the black soil plains (1899). This robust image of draught horses straining to carry a heavy load of wool bales signified, above any other painting of the time on the cusp of Federation, that the New World had finally been conquered.

For more than three decades Lambert represented the gallery trustees’ ideal of contemporary genius. He was not an unreasonable hero for them to espouse, for as we can see from the monumental portrait group Holiday in Essex (1910), his assurance of tone and paint-handling on a large scale had a kind of Renaissance elan that won the respect of the Chelsea culture in London.

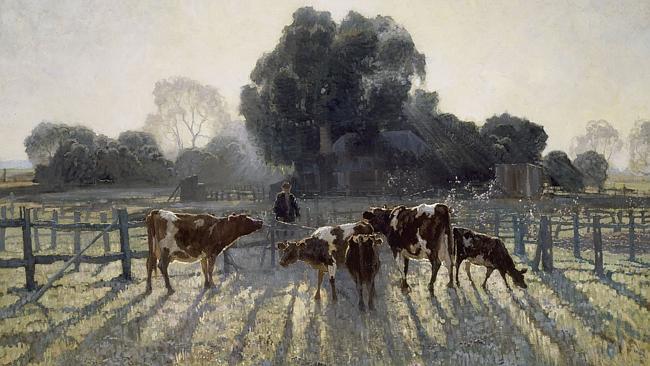

At the same time, on his return to Sydney in 1921, he developed a sympathy towards the cause of young modernists who were trying to be more adventurous. Parallel to Lambert was the local landscape painter Elioth Gruner, contemporary of Hans Heysen and considered by some to be the Irish-Australian heir to Streeton.

Over the years the gallery acquired the works en masse of Lambert and Gruner — both students of Ashton — regarding them, it seems, as the alpha and omega of best current practice; one the master of the human image, the other of landscape.

This period reached its climax with the death of Gruner in 1939, when his luminous Wynne Prize-winning painting Spring frost of 1919, a tour-de-force of morning light in a pastoral setting with impeccable control of broken brushwork, was donated to the collection. Meanwhile, outside the gallery walls, a new generation of agents for contemporary art had begun to raise their voices.

During the first half of the 20th century the gallery also had the lucky knack — allied with insightfulness — of securing singular masterpieces by Lambert’s fellow expatriates, fleshing out a period when the majority of Australia’s most talented artists were abroad. These include Hugh Ramsay’s The sisters (1904), painted shortly after the artist’s return to Melbourne, prior to his tragic early death from tuberculosis, Rupert Bunny’s A summer morning (c. 1908), and Emanuel Phillips Fox’s The ferry (1911); the latter two painted in Paris and now ranked alongside what might be termed the great destination paintings of the old courts.

Acquisitions continued in this vein in the decades following World War II, including another catch-up phase in the 1960s to meet the deadline of the Captain Cook Wing. For just as the gallery had once needed to address the paucity of early colonial works, it now found its representation of the first stirrings of modernism inadequate. Hence, in 1960, the purchase of Roy de Maistre’s Rhythmic composition in yellow green minor (1919) — considered one of Australia’s earliest abstract paintings — and, a year later, Roland Wakelin’s Down the hills to Berry’s Bay (1916). During the 60s the gallery also purchased important paintings by Sydney pioneers of abstraction Ralph Balson and Grace Crowley.

Until then, perhaps the most modern painters the gallery had committed itself to without much challenge were Margaret Preston, William Dobell and Russell Drysdale. Preston’s Grey day in the ranges of 1942 hinted at possibilities of fusion with Aboriginal art forms prescient of an indigenous revolution to come; and Dobell’s Portrait of Margaret Olley of 1948 carried the baggage of his controversial Archibald Prize-winning portrait of Joshua Smith of 1943, when legal action claiming he had perpetuated a grotesque caricature in the cause of modernism seriously damaged his health. In between, Drysdale’s The Walls of China, Gol Gol (1945) had nudged the Australian gaze unknowingly towards a metaphysical notion of space and surrealism through his encounters with the outback.

Over the past four decades or so, painting has come to share the centre stage of contemporary art — and even step aside from — alternative forms of practice, but the gallery has continued to represent its current state, as well as be mindful of the gaps that become obvious when tracking back through history. For it to have done this with success, one must acknowledge the increasing necessity of private benefactors.

One of the most important has been the Art Gallery Society of NSW. It helped secure Lambert’s long-lost masterwork Holiday in Essex in 1981; then, in conjunction with James Fairfax in 1991, Grace Cossington Smith’s The curve of the bridge (1928–29), arguably one of the most radiant Australian paintings of the modern age; Brett Whiteley’s paean to female sensuality Woman in bath (1963–64) in 2000; and James Gleeson’s great surrealist epic The Ubu diptych: Ubu regnant and The senior mandarin (2004) in 2005, to mention just a few.

The Gleeson O’Keefe Foundation has been a more recent supporter of the Australian collection since it funded in 2008 the acquisition of Tom Roberts’s Fog, Thames Embankment (c. 1884), a talisman for the 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition in Melbourne in 1889. But it would be hard to better its funding of Sidney Nolan’s First-class marksman (1946), acquired in 2010. This image, from Nolan’s first Ned Kelly series — long separated from the group now housed at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra — with a subversively wild rendering of the Australian landscape glowing like a dream beyond the incongruous black slab of Kelly’s helmet, is surely among the most exciting declarations of Nolan’s originality.

Why have I written a book dedicated only to the practice of painting? Why, when artists have for several decades expended so much creative energy towards a bewildering array of media, hungry for space, technology and collusion with the four-dimensional culture of theatre? What is the future of the basic picture plane with pigment? Well, although we now swim in a broad estuary of exciting possibilities, occasionally it is refreshing to go back along the river and follow the source of where we came from to look for an answer, before becoming swamped by the great dispersal of ambition in the current scene of contemporary art.

As Robert Hughes said in 1980: “The ultimate business of painting is not to pretend things are whole when they are not, but to create a sense of wholeness which can be seen in opposition to the world’s chaos.”

Barry Pearce was head curator of Australian art at the Art Gallery of NSW until 2012. This is an edited extract from his book 100 Moments in Australian Painting (New South Publishing, $49.99).