Adelaide Festival ‘exposed’ as WOMAD heats up for Mad March

‘Mad March’ has revealed more than one naked truth in the festival-fuelled South Australian capital.

It might have been the talk of the dance world, but in Adelaide it barely warranted a whisper. Boris Charmatz, the acclaimed choreographer and director of Pina Bausch Tanztheater Wuppertal, one of the world’s most acclaimed contemporary dance companies, sensationally had left the organisation, less than two years into the job. Not just that, the terms of his contract termination were a tightly held secret. Tongues around the dance world were wagging. What had gone down? The ABC on Saturday – a week after the public announcement – breathlessly reported a piece quoting Charmatz, without a single mention of his departure. Adelaide Festival declined to respond to a query about Charmatz’s contract termination. Why the silence? Why the mystery? What culture lovers would give to know more. To peek behind the curtain …

Well, if the latter was the wish of Adelaide Festivalgoers on Monday evening, they got it, in a manner of speaking. Patrons might not have been illuminated about the defection of one of the world’s top choreographers from one of the globe’s top companies currently in residence in their city, but they were invited behind the curtain – and beyond the proscenium arch – at Adelaide’s Festival Theatre, to witness the debut of Club Amour.

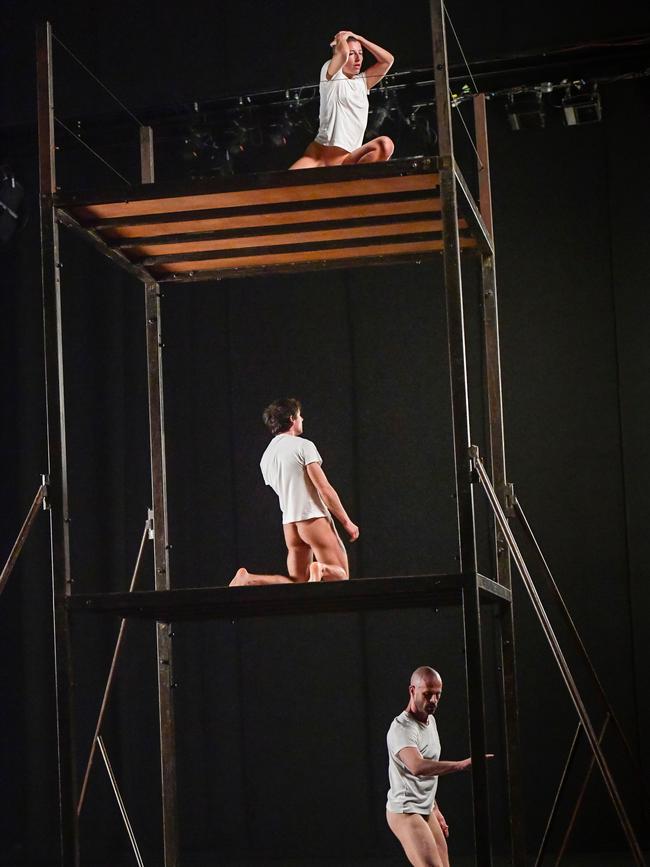

The triple bill began with two of Charmatz’s works, Aatt Enen Tionon! and Herses, Duo, and both were set against the backdrop of the main stage’s backstage precinct. The former featured three performers on a 6m-high three-tiered scaffold, and invited the contemplation of personal isolation and, well, of genitals. The dancers – each wearing a white T-shirt and naked from the waist down – performed singular, sometimes violent movements to a rock soundtrack, not once interacting with each other.

Striking as the spectacle was, the work itself left many in the audience scratching their heads. The piece’s title is a play on “Attention”, and, at the very least, it demanded just that: observation. Indeed, at times, it was hard to look away.

It was followed by Charmatz’s shorter and far more compelling Herses, Duo, a poignant depiction of life, in all its pain, tragedy and triumph. The performers, including Charmatz himself – a naked male and female; like a brace of marble statues gracefully brought to life – variously carried, lifted and trampled each other in a picture of breathtaking corporeal beauty.

But it was the work of legendary company founder Pina Bausch, who died in 2009, that many had come to see, and her classic Cafe Muller – regarded as one of the most important contemporary dance works of the 20th century – was momentous. The audience had been respectfully relegated to the auditorium to witness the piece, all moving tables and chairs and bodies. Set to the music of Henry Purcell, the 1978 work was inspired by Bausch’s childhood memories of her father’s cafe in Germany during World War II, and its staging was another reminder, were one needed, of the reputational power of Adelaide Festival to commission the world’s best arts companies.

The bill’s programming was thanks to former director Ruth Mackenzie, who herself sensationally left her position 18 months ago, midway through her tenure, to take up a position with the South Australian government. Kudos then must go to Brett Sheehy, the safe pair of hands and seasoned festival boss who has seen through this 2025 iteration as an emergency interim director, and who by all accounts is very happy to be passing the baton to incoming 2026 chief Matthew Lutton.

There were reckonings of a more political kind unfolding across the city at WOMADelaide, the country’s largest and most important world music event, in the Botanic Gardens. WOMAD courted controversy 18 months ago when it “deferred” the appearance of Palestinian-Jordanian band 47Soul. The reasons for the quartet’s cancellation in November 2023 were cited by longtime WOMAD director Ian Scobie as “safety concerns” – the festival apparently feared protests could derail the event, and attempted to make it as apolitical as possible by hosting no artists from Israel or Palestine – but that line was subsequently criticised by billed artists and arts leaders, most notably Adelaide Writers Festival chief Louise Adler, who reportedly called the reasoning a “furphy”.

WOMAD ultimately issued a statement on social media, saying: “We hear you, we’re sorry – we don’t always get it right.” The festival insisted 47Soul would be welcomed in 2025. And so it was. WOMAD did not program an Israeli act for this year’s event. Scobie declined to speak about that decision.

On Saturday afternoon, 47Soul returned (but for one member, who did not travel to Australia), and the band had a message for the crowd, and for the festival.

“It’s not easy to perform as your mother’s house is being demolished while you’re on stage,” said band member El Far31. “I can’t tell if (performing) is therapy or torture anymore.”

He continued: “I’m not going to go into details (about last year). I just want to say it was frustrating for us – the justification of why you would withdraw an invitation – but, look, we also live in the real world and we see shit and we understand it. We solved it diplomatically.”

With that, the band broke out their brand of Shamstep, the Levantine genre of electronic dance music combining digital instruments with traditional Dabke music.

While a would-be cyclone was threatening Queensland and northern NSW, Adelaide had only blue skies and high temperatures to offer. As the mercury nudged 39.5C over the weekend, two of the festival’s big bookings in Britons Nitin Sawhney and singer PJ Harvey had got things under way. Sawhney, with full band and singers, performed his trademark fusion of electronica and South Asian traditional music to a packed-out paddock before Harvey, who at 55 looks as though she hasn’t aged since her heyday in the 1990s, showed she had lost none of her skill or stage presence. Her ethereal vocal floated above the throng – it seemed half of Adelaide was there – and out over the botanic gardens towards the city as a stirring reminder of her unique artistry.

They call this long weekend Mad March in the SA capital. Adelaide Festival, the country’s most prestigious, hits its straps in the middle of its three-week run; WOMAD takes centre stage, Adelaide Writers Week finishes up; and the Adelaide Fringe Festival – the country’s largest single arts event – seems to get bigger and better each year. On Saturday evening, the north end of Rundle St was closed to traffic. The usually busy thoroughfare was replaced with pop-up bars and street parties as revellers danced, drank and sang into the wee hours.

The New Orleans-style Mardi Gras street party, however, could hardly have been in more stark contrast to the scene the previous day inside the Grainger Studio where the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra was putting people to sleep. The ASO, conducted by David Sharp, played to a house full of music lovers, many of whom were lying on yoga mats. The hour-long concert, Echoes, part of its Sanctuary Series, took in compositions by Toru Takemitsu, Tom Coult, Debussy and Arvo Part. Ushers requested patrons not applaud between pieces. They said nothing, however, of parasomnic episodes, and midway through the performance an audience member affirmed with an audible snore the exquisitely hypnotic – if, apparently, somnolent – beauty of the playing. Associate concertmaster Cameron Hill’s attempt to stifle a giggle was a lovely moment.

At the Odeon in Norwood, in the city’s north, Daniel Riley’s Australian Dance Theatre was celebrating its 60th anniversary year with A Quiet Language. Riley’s moving work for ensemble and solo musician and composer Adam Page took place on a stage that intersected its audience. The performance, which charts the history of Australian contemporary dance and ADT itself – the country’s oldest continuing contemporary dance company – began with two dancers and grew to a cast of six. Page, saxophones and mixing loop station at the ready, created an at-times haunting, driving score in real time to which the cast evolved before the audience’s eyes.

Hundreds on a steamy Saturday escaped the heat for the airconditioned comfort of the Space Theatre, which was hosting Britain’s Forced Entertainment’s Table Top Theatre. Over eight days, the company performed each of Shakespeare’s 36 plays, beginning with Corliolanus and ending with The Tempest. This, truly, was Shakespeare as we had never seen it. Essentially this is pantrymime: the “performers” are condiments. A single live narrator at a table uses pantry items – salt and pepper shakers, a soup can, a candle, a cheesegrater, for example – to represent players in the works.

Timos of Athens, whose titular character was played by an empty sugar shaker, was so well executed one almost forgot for a moment the objects were not actual actors. The delivery of the following play, Two Gentlemen of Verona, was clunkier but one can, and indeed should, forgive a narrator’s momentary lapse of memory amid a program as dense as this. Table Top is truly imaginative and clever theatre.

The scenic route through the Botanic Gardens to WOMAD was interrupted this year by the long-running, and sprawling, exhibition by internationally acclaimed glass artist Dale Chihuly, whose hypercoloured works were dotted throughout the precinct. While the high-profile exhibition was worth a glance, there was a far more interesting free show of local glass artists at the Jam Factory in the west end. Gathering Light, featuring some dazzling pieces by local artists – Jessica Murtagh and Liam Fleming, among them – made a bold statement during festival time (at a non-festival venue) of the city’s deep well of talent.

Nonetheless, this writer eventually found his way past the Chihulys to witness the impressive lineup for WOMAD’s final days. Most notable were the incomparable Portuguese traditional fado singer, Mariza; genre-hopping British jazz innovator Shabaka; Serbian Balkan fusion figure Goran Bregovic and his Wedding and Funeral Band; the legendary Sun Ra Arkestra, still going strong after 70 years; Irish electro producer and singer Roisin Murphy, and; one of the biggest stars of contemporary music, Nils Frahm, who played a warm-weather late-night set of ambient electronica to a humming crowd.

By the time WOMAD wrapped on Monday evening, more than 700 artists from 35 countries had performed. The festival, by the time of going to press, could not provide attendance numbers but anecdotal evidence suggested Cyclone Alfred might have affected visitations; historically, 40 per cent of attendees have been from interstate.

The weekend’s final word, however, had to go to the Art Gallery of South Australia, and its excellent Radical Textiles exhibition. A steady stream of visitors the day The Australian attended filed through to see the work of more than 100 makers charting 150 years of design. While crowds flocked to 19th-century British artist William Morris’s hand-loomed large-scale tapestries, and the colourful, geometric beauty of French artist Sonia Delaunay’s handiwork, it was a pair of pink shorts on the final wall that stole the show.

The polyester pants, of course, belonged to former SA premier Don Dunstan who famously in 1972 proudly tucked himself into them on the stairs of Parliament House as a statement of solidarity for equal rights and democracy. Known as one of the great patrons of the arts, Dunstan and his legacy have rightfully loomed large – far larger than those tightly tailored duds – over Adelaide, its world-class festivals and the Australian arts community for a half-century.

Indeed on Monday, as Charmatz’s curious, multistoreyed no-pants-dance played out in the very festival centre Dunstan was so instrumental in building, one couldn’t help shake the thought that the performance might have benefited from the former premier’s best-known sartorial choice.

But Dunstan surely would have had none of that suggestion. Freedom of expression was central to his beliefs, and remains so to his legacy. He donned pink shorts for many causes, not least of which might have been that one day – in Adelaide, in the name of culture and for no other apparent reason – artists might have the right to wear none at all.

Tim Douglas travelled to Adelaide as a guest of Womadelaide and Adelaide Festival.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout