The day Brett Whiteley paid price for hunger that drove him

WHILE the art world and beyond was shocked, no one was surprised by the death of artist Brett Whiteley.

THE sense of inevitability didn’t mask the shock. Brett Whiteley, the restless, dynamic, curly haired artist whose struggle with addiction was almost as well known as his work, was dead at 53.

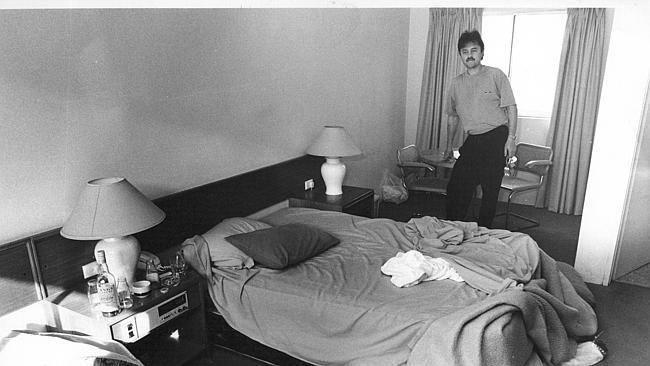

The end came on June 15, 1992, inside room four at the Thirroul Beach Motel on the NSW south coast. It was a Monday night. There was a near-empty bottle of whisky and four syringes.

An old friend, the artist Tim Storrier, identified the body the next morning. Back in Sydney, Whiteley’s former wife Wendy was on the phone, chatting to a friend, when two policemen knocked on the door. “I went into deep shock and horror, but I can’t say I didn’t expect it.”

A small crowd gathered at the house in Lavender Bay, the harbourside suburb on Sydney’s lower north shore. Brett and Wendy had divorced three years earlier, but the news struck hard.

Their story had been intertwined for more than three decades, and this was the house they found together. Wendy put in a call to London. Arkie Whiteley was about to learn that she had lost a father.

1992: The landscape diversifies

The art world was stunned, but this was a loss felt across Australia. Paul Keating said in statement he had a “high personal regard for him and for his work”.

“His immense contribution to our nation’s art and culture will be remembered,’’ the former prime minister said.

The value of Whiteley’s art continues to soar; students study his career and critics still argue about his legacy. But, 22 years on from his death, much has changed, and some of the people in Brett’s life are gone: Arkie died in 2001, one year after Janice Spencer, Whiteley’s girlfriend, who fought her in court over his will; Brett’s mother Beryl died in 2010.

Wendy is still at Lavender Bay, where her home is filled with pictures from different stages of Whiteley’s career. Over the years, she has found some peace with her former husband’s memory. Now 73, she oversees his estate with a keen eye and protective, affectionate attention to detail.

She helped establish the Brett Whiteley Studio in inner-city Surry Hills, where his former home is now managed by the Art Gallery of NSW as a living museum, open three days a week.

And she has become a formidable cultural figure in her own right, transforming the mess in front of her house into a sumptuous garden that is now a Sydney landmark. Most weekends, families and couples wander through the trees as Wendy works quietly among them.

Two other major artists died in 1992: Sidney Nolan, Australia’s most successful artistic export, and Francis Bacon, Whiteley’s friend and mentor. Both were, of course, many years older than Whiteley, who lived at full throttle, as he put it, from an early age.

Whiteley moved to London in 1960, and within a year the Tate had bought one of his pictures. In 1967, he and Wendy moved to New York, where they lived in a penthouse at the Chelsea Hotel, until Brett fled to Fiji two years later. A drug conviction soon led to their expulsion from Fiji. They returned to Sydney — preceded by their reputation — and settled in Lavender Bay. Whiteley’s profile rose, huge crowds drawn to his shows and steadily rising prices. At the time of his death, the Art Gallery of NSW was in the early stages of planning a retrospective.

Whiteley’s death, while sudden in its impact, did not come without warning. The 1978 Archibald Prize, for instance, went to Art, Life and the Other Thing, a self-portrait in which Whiteley presented in one panel a screaming, anguished beast with needles in its arm. (He won the Archibald trifecta that year, taking out the Wynne and Sulman prizes, too.)

He had wrestled with heroin since the mid-70s, and spoke candidly about the difficulties of separating his art from his addiction. In a letter to his mother in January 1979, his anxieties were clear: “I am fighting the biggest struggle of my life at the moment. I am trying to become a great man.”

He reflected on these issues in public, too. In September 1986, talking to Phillip Adams on radio 2UE, he said many of his heroes were addicts, and he had become the “problematic continuation of that tradition”.

There was a price, he said, for the hunger that had driven him since his teenage years. “I have arrived at a point in my life where unless I revise, unless I mature, unless I shape up, unless I look at my character defects, unless I get a sobriety, I will spin out.”