Cannon Hill massacre: Children and mothers slain in 1957 shooting rampage

WHAT triggered the shootings will never be known, but by the end four little girls and two mothers lay dead — one child still clutching the lunch money she was going to take to school. Only the actions of a brave policeman stopped further carnage.

Our Criminal History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Our Criminal History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

STUMBLING on sea legs, Marean and Gisela Majka filed ashore with the hundreds of survivors whoÂ’d come for a new life.

They’d lived through years of war, through bombs and death, through loss and atrocities, prison camps and torture.

But there was hope in this promise of a new beginning.

It was 1950 and the SS Amarapoora had docked in Newcastle, NSW, after six weeks at sea.

Once a hospital ship, the Amarapoora had been handed over to the Ministry of Transport to carry prisoners of war to Australia.

More than 600 walked ashore that day. They were taken in buses to a nearby camp where each new arrival was allocated a tent, a coat, boots and a hat.

The men were given a small amount of money for incidentals. Haircuts and cigarettes.

They didn’t have much but they had hope. Soon they would find jobs. Learn new skills. Take on a plot of land or a small house. Australia was a safe place, a place to raise a family and start again.

For Marean Majka, it was a place to start afresh.

The Polish migrant was 28 years old when he stepped ashore with his bride.

He’d survived five years in a Nazi camp. That survival was no coincidence, according to some. Rumours would abound that Marean had curried favour with the Germans by pointing out dissenters and spies in the camp.

Marean would point his finger and a prisoner would be executed.

But despite spending five years in a German concentration camp, Marean arrived in Australia with a German woman at his side.

Many of those on board the Amarapoona would find work further north in Queensland. The Majkas were among them, landing on their feet in Brisbane where Marean found work as a moulder in a Bulimba metal factory.

Home was a dirt strip in Cannon Hill called Narela St, where they set up in a small fenced allotment among raised fibro cottages.

They’d been in Australia two years when their daughter Shirley was born.

Around Christmas, 1956, neighbours pitched in to help the Polish man move his house further back on the allotment. They respected him. He was quiet and likeable. He was a hard worker.

Constable John Strickfuss, known as Jack, was one of the neighbours who pitched in that week. A hard worker himself, Jack was a highly esteemed policeman with a wife and daughters of his own.

On February 18, 1957, Const Strickfuss dressed for work and sat down to breakfast. It was 7.30am when the sounds of gunshots rang through the air.

A dog yelped and screamed. Some neighbours thought they were hearing the sounds of an animal being put down. They carried on with their morning, thinking nothing was wrong. Const Strickfuss didn’t.

The officer leapt to his feet and took off down the street. There was smoke coming from the Majka house.

He shouldered the front door open and burst inside. Heat and smoke blocked his path like a wall. The officer backed up and ran for his garden hose.

Across the road, there was another fire. Neil and Belinda Irvine lived opposite the Majkas with their children. The residents of Narela Street were spilling onto the road.

Const Strickfuss grabbed his hose and ran with some of the neighbourhood men to the Irvine place.

He was metres from the front door when the shots rang out. One, two, three, four, five in quick succession. He felt their wind as they whistled by.

He didn’t stop or retreat or drive for cover. A few short steps had him crashing into the locked front door as he attempted to break it down.

The other men, neighbours Jim Ainsworth and Fred Ganter, dropped their hoses and ran for cover.

They shouted to each other and ran for their own rifles. One ran to get Const Strickfuss’ service revolver.

The policeman scouted the house and spotted a man in the sitting room with a rifle. The man spotted him and he threw himself to the ground as more shots rang out.

More shots came from the bedroom window before a heavy thud silenced everything.

Long seconds passed as Mr Ainsworth ran towards the house holding Const Strickfuss’ revolver.

The officer took it gratefully and ran to the rear of the house.

There were no more shots now. A baby cried somewhere inside.

Const Strickfuss threw the back door open and ran inside.

A man’s body lay on the floor of the front bedroom. A rifle underneath. It was Marean.

In the kitchen were four more bodies.

Belinda Irvine was dead, lying next to her daughters Annie, 12, and Belinda Maureen, 9. Another little girl, Lynette Karger, aged 10, lay with them. Lynette liked to walk to school with the Irvine sisters and had called in to collect them.

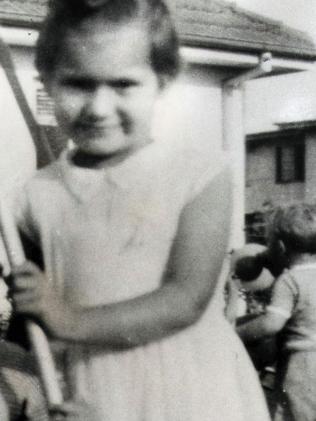

She lay in her school uniform, her lunch money inside a handkerchief still clutched in her hand.

Mother and children lay in a pile, their bodies on fire.

The horrified policemen tried to douse the flames as he searched for the crying baby.

Six-month-old Elaine Irvine lay under her dead mother, a bullet wound in her tiny foot. The bullet had passed through her mother and hit her. Flames had burnt her skin.

Neighbours shouted for a taxi and bundled the little girl off to hospital.

Marean had murdered the family before turning the gun on their dog.

He’d narrowly missed people in the street as he’d fired through the front windows before turning the gun on himself.

He’d seen Jack Strickfuss coming for him, an unarmed man with all the courage in the world.

Across the road were more horrors. With the flames at the Majka house under control, neighbours discovered Gisela and little Shirley dead. Marean had used a knife and hammer to murder his wife and daughter.

He’d killed them and sat in wait until Neil Irvine left for work. Then he’d set his house on fire and crossed the dirt street, rifle in hand.

Marean still had a pile of ammunition at the ready when he turned the gun on himself as Const Strickfuss approached. An entire primary school of children were making their way to the school grounds at the back of the Irvine house when the officer’s actions put an end to a gunman’s rampage.

Const Strickfuss was awarded the prestigious George Medal for the courage he showed.

Jim Ainsworth and Frederick Ganter received Queen’s Commendations for Bravery.

Neil Irvine would take his surviving daughter to Adelaide, where they started a new life together.

Lynette Karger’s mother died two years later of a broken heart.

No reason was ever given for the mass murder. Marean, a survivor of one of history’s worst atrocities, simply snapped.

- This is an edited version of a story first published in December 2014

Originally published as Cannon Hill massacre: Children and mothers slain in 1957 shooting rampage