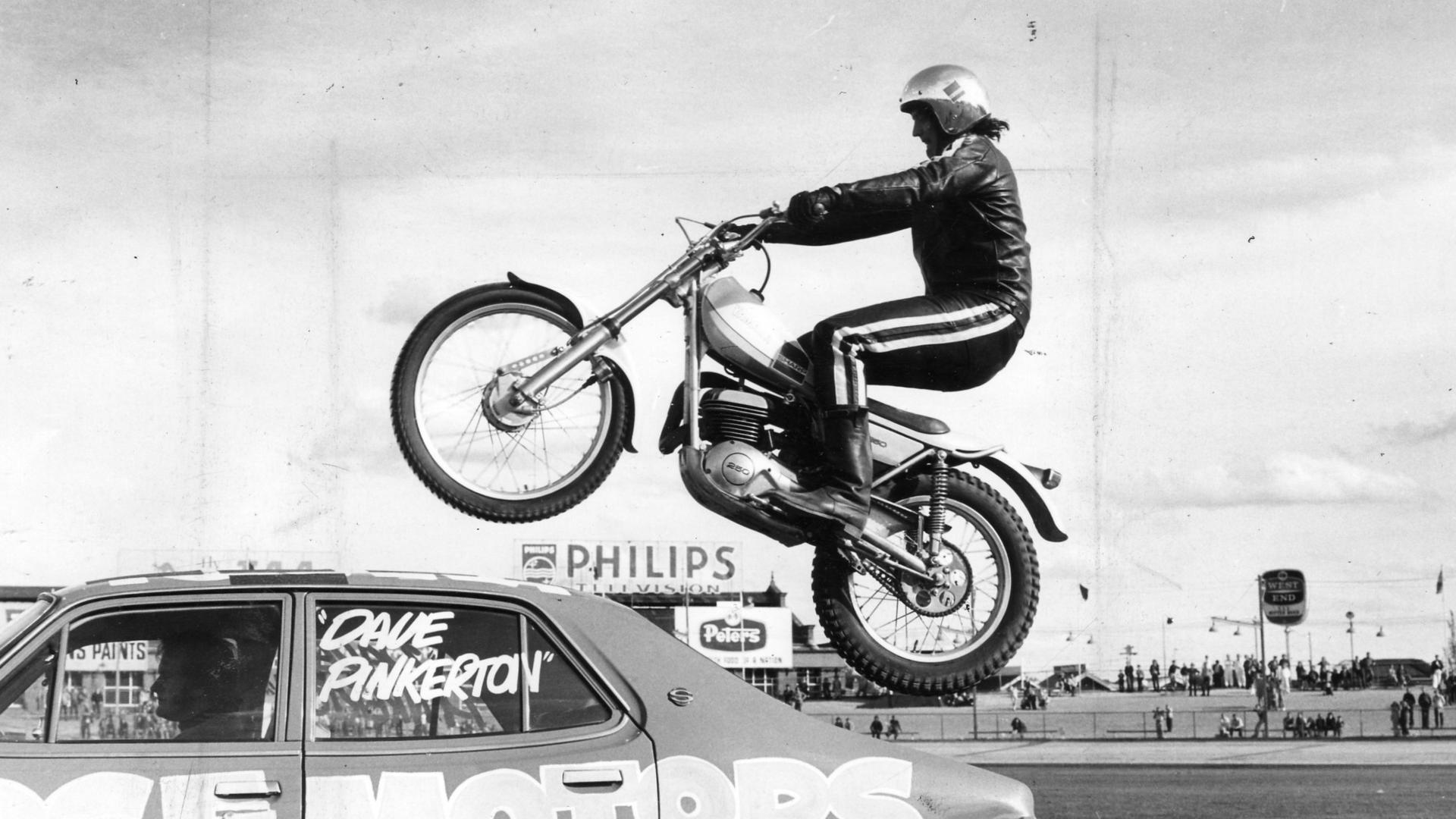

IN 1973, more than a dozen inmates from Yatala prison — including murderers — were given day release to perform puppet shows for kids at the Royal Adelaide Show. Hard as it is to believe, this brilliant plan went seriously wrong.

IT’S September 1973, and South Australia is getting freaky. Our Premier is wearing pink shorts, hippies are dropping acid and SA prison authorities think it’s a great idea to let convicted murderers perform puppet skits to kids at the Royal Adelaide Show.

The idea was certainly novel, even for the 1970s, but in any era it could at best be described as breathtakingly naive.

Form a puppet troupe by recruiting 15 inmates from South Australia’s highest-security prison and let them perform 18 shows a day at the Royal Adelaide Show.

What could possibly go wrong?

Nearly 45 years on, it’s hard to imagine such a self-evidently crazy concept ever being approved.

It sounds like a script for a sitcom that never made it into production, but for five days, the prison authorities behind this real-life farce were the ones left looking like clowns as they searched for two convicted murderers who used the chaos at the crowded Showgrounds to slip away and go on the run.

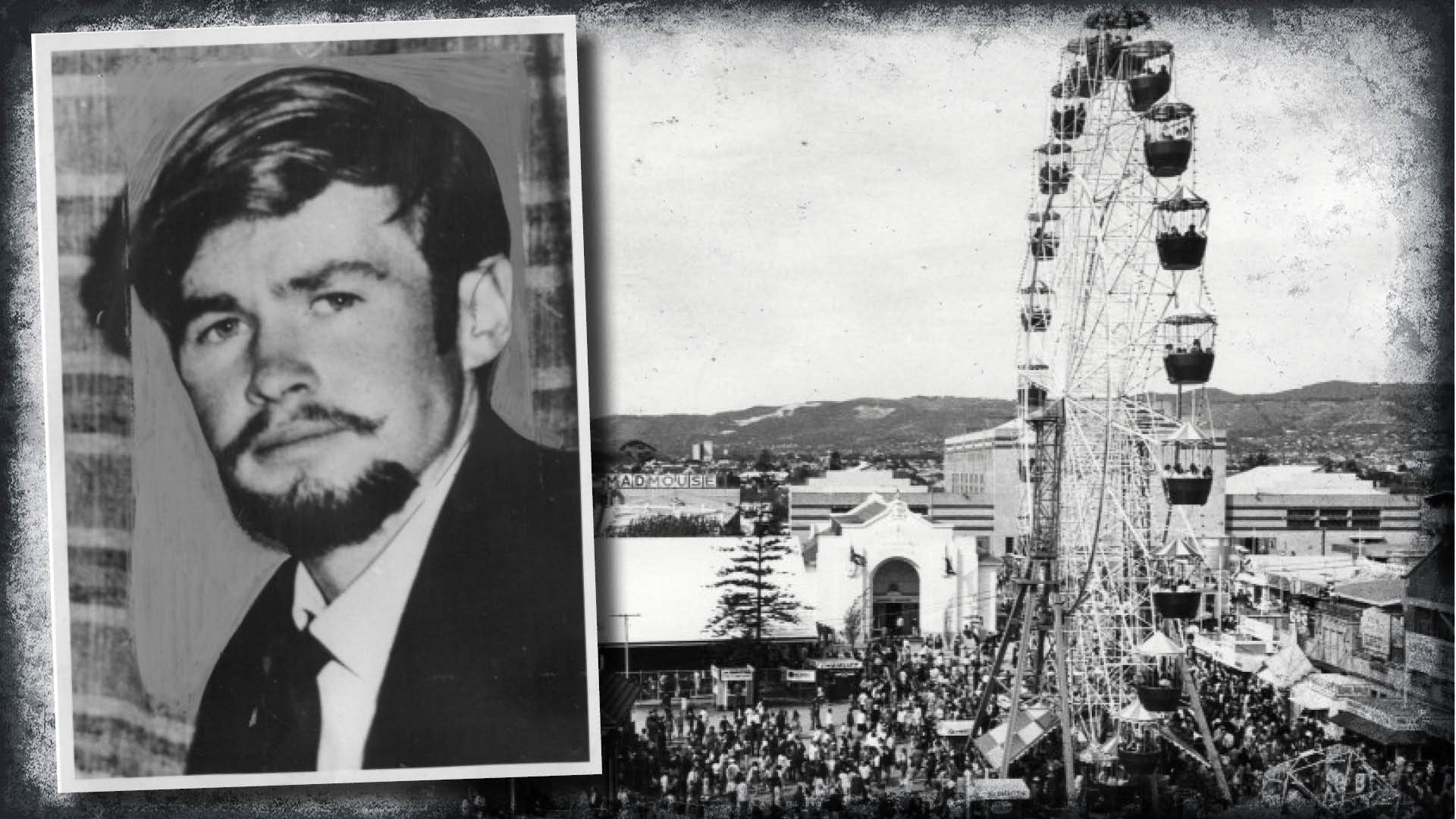

At dusk on the evening of Saturday, September 8, the marionette production of Snow White was nearing its end, and the Yatala Prison Puppet Troupe had won glowing reviews for their performance and exemplary conduct.

But a week of ushering noisy kids and parents into Centennial Hall 18 times a day was overtaken by temptation for three prisoners, who waltzed out of Wayville Showgrounds unchallenged.

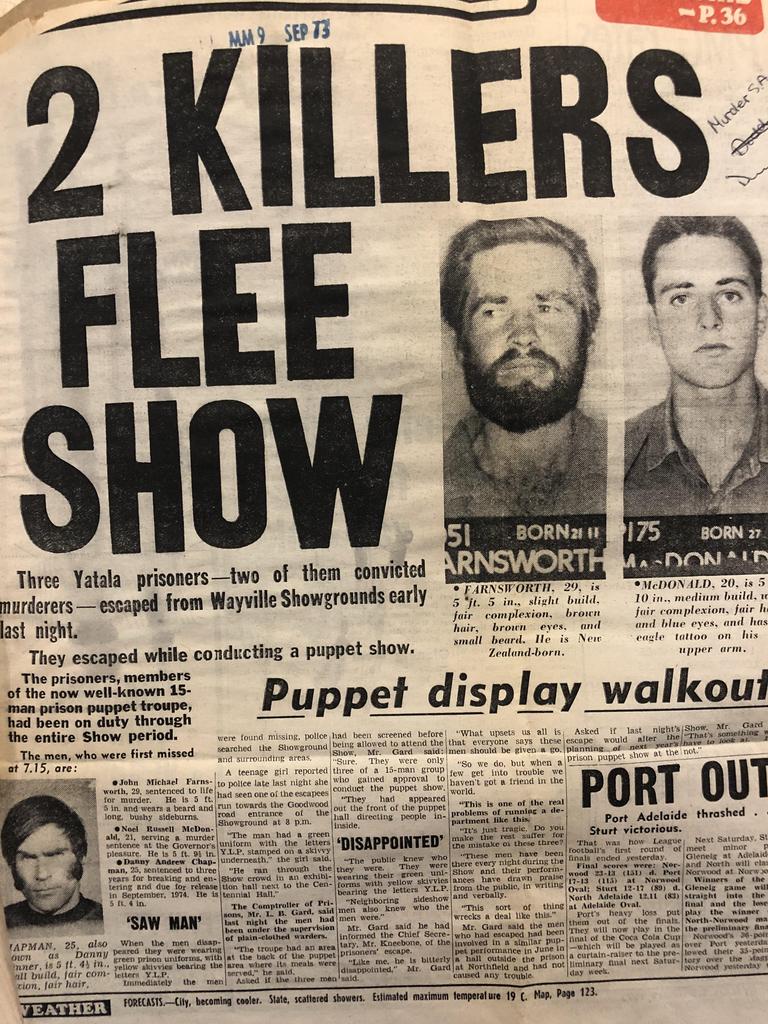

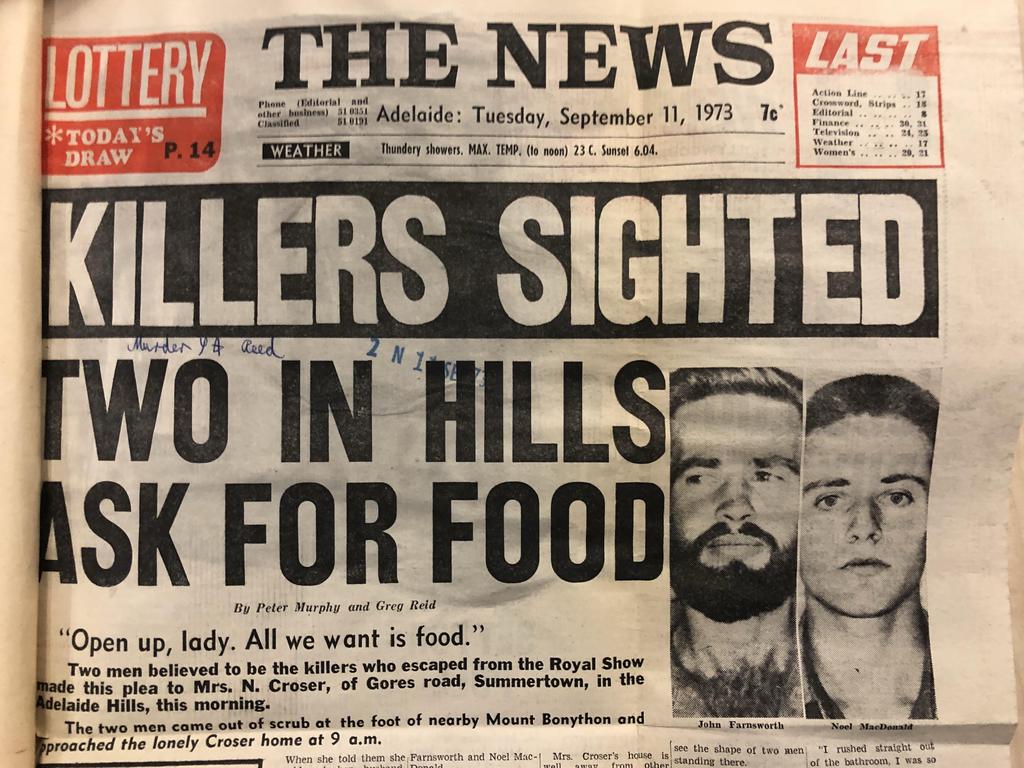

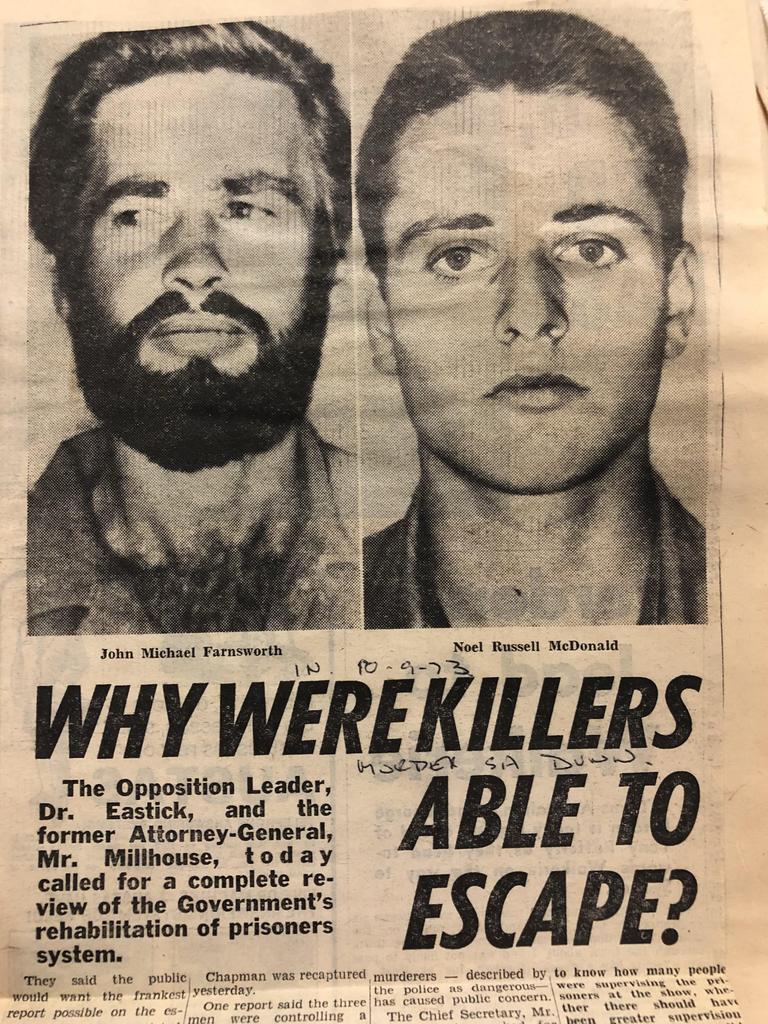

Wearing green jail uniforms and yellow skivvies with YLP emblazoned across the chest, convicted murderers John Michael Farnsworth and Noel Russell MacDonald sparked one of the biggest manhunts ever seen in the state.

Farnsworth, 29, and MacDonald, 21, were initially joined by petty thief and burglar Danny Andrew Chapman, who was back behind bars within a day.

Deprived of affection, Chapman headed straight to his girlfriend’s home and was detained by members of the public then taken by police.

But killers Farnsworth and MacDonald were gone, and would evade arrest until giving themselves up five days later.

The escape dominated the headlines, as the public joined politicians in asking why two men convicted of shooting murders had been given a free ticket to freedom.

How Farnsworth convinced jail bosses to allow him to take part in the first place remains a minor mystery.

Only six years earlier, the New Zealander had been doomed to hang at the end of a noose when he received the death penalty for the shooting murder of a woman in the state’s Far North.

Farnsworth was in his early 20s when he murdered Sheila Rose Reed, who was found dead with her husband at Mount Willoughby, about 160km from Coober Pedy, in July 1967.

Farnsworth’s initial death sentence was later commuted to “life imprisonment with hard labour” — a sentence he received for only the murder of Mrs Reed, not that of her husband Thomas.

In keeping with the curious quirks of the state’s criminal law at the time, Farnsworth was not charged with Thomas Reed’s murder, as prosecutors accepted the single plea in satisfaction of both charges.

The couple’s decomposing bodies were found about a week later, near their caravan just off the main highway to Alice Springs.

Farnsworth had shot them both twice in the head with a high-powered rifle, before taking off across Australia and across the Tasman to his homeland of New Zealand.

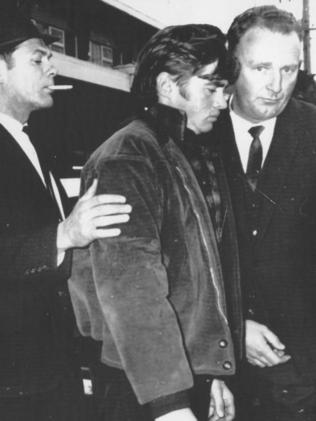

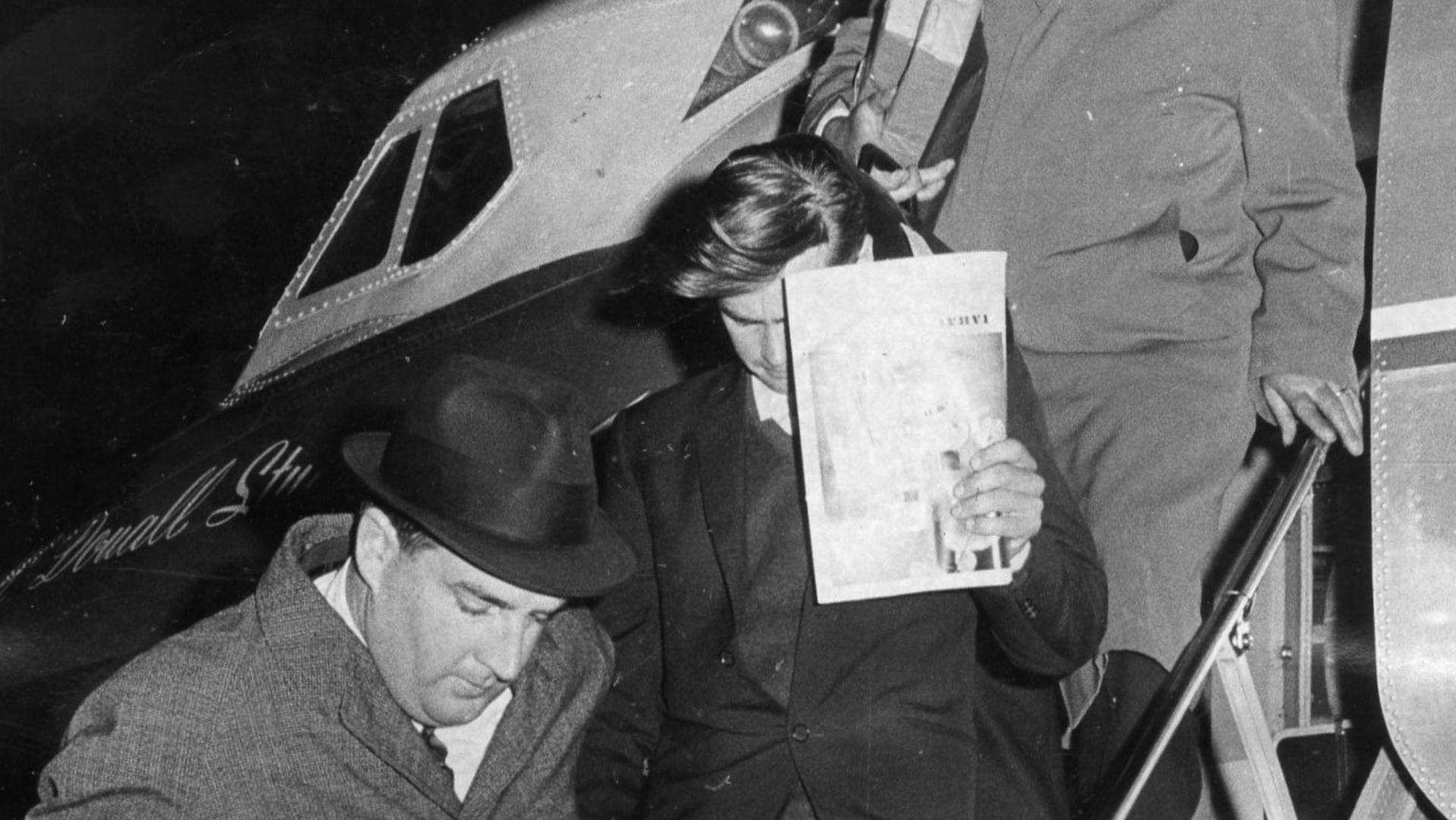

But within a matter of weeks, police arrested Farnsworth in Rotorua and he was extradited back to Adelaide to face his future, which at the time seemed unlikely to include puppetry.

Now, Farnsworth was again on the lam, this time with a fellow convicted murderer for company, the younger and impressionable MacDonald.

As the pair ventured towards sanctuary in the Adelaide Hills, panicked police launched a belated attempt to search cars leaving Wayville Showground.

By Sunday morning, dozens of police had embarked on a massive manhunt, and back in the city, there was some explaining to be done.

Those awkward questions were left to the Controller of Prisons — the ironically named Mr L Gard.

Mr Gard was forced to acknowledge what some astute observers had already noticed, namely that “mistakes had been made” in picking the prospective puppeteers.

In defending the debacle, Mr Gard put on a brave face as a separate inquiry was launched by his superior, Chief Secretary Mr Kneebone.

Mr Gard’s frustration was matched by a seemingly genuine surprise that two convicted murderers had not played by the rules.

“We didn’t have any fears at all that there was going to be any trouble,” he told reporters.

“Farnsworth and MacDonald had both proved themselves worthy of taking part in the troupe … they earned the right to become prisoners needing less security.”

At a time when authorities began searching for the elusive line between traditional punishment and the relatively unknown concept of rehabilitation, Mr Gard was clearly disappointed in both the escapees and the headache they had caused his department.

“Something like this ruins the whole rehabilitative effort. Everyone says these people must be given a go and when a few get into trouble, we (the department) haven’t got a friend in the world,” Mr Gard lamented.

The contrite controller said witnesses had seen the men running towards the Goodwood Rd exit, remaining out of sight for some time despite dozens of roadblocks and raids upon homes occupied by associates.

As hours ticked into days, the questions grew louder and the discontent of the public quickly morphed into a political crisis for the department, which to paraphrase Mr Gard, “barely had a friend left to offer a kind word.”

“This is one of the real problems in running a department like this. It’s just tragic. Do you make the rest suffer for the mistake of these three?” Mr Gard mused to reporters.

Despite the admission, Mr Gard at that point had not completely rejected the notion of allowing the puppet troupe to return in 1974.

“That’s something we will have to look at. This sort of thing just wrecks a deal like this,” he said.

Other developments included the revelation that two members of the Yatala puppet troupe had also escaped in April 1967, during a performance to psychiatric patients at Glenside Hospital.

The government’s embarrassment descended into outright fear that Farnsworth or MacDonald could hurt or even kill innocent people.

By the end of the third day, the Dunstan government stumped up a whopping $10,000 reward for information leading to their capture — clarifying that the handsome reward was not available to serving police.

The $10,000 lure sparked a furious debate on whether it could encourage vigilante bounty hunters, and if it should have outstripped the reward offered for information on the still-unsolved disappearance of schoolgirls Joanne Ratcliffe and Kirste Gordon from Adelaide Oval the previous month.

Farnsworth had grown up in the dense greenery of New Zealand and was considered an elite marksman, placing police on high alert in fear the pair may have armed themselves.

But in truth, much of Farnsworth and MacDonald’s free time was spent hiding in the trunk of a large dead oak tree near Summertown.

After two days in the cold with no food, Farnsworth and MacDonald crept towards a farmhouse on Gores Rd, at the foot of Mount Bonython just before 9am on Monday, September 11.

Inside and shaking with fear was the female resident, acutely aware the two men knocking at her door were likely killers on the loose and that her husband and son had gone to work.

“Open up lady, all we want is food,” Farnsworth boomed to the terrified occupant.

Peering through the bottle-glass window near her backdoor, the woman told reporters she could see the silhouettes of two men outside.

“Then a head came up and this man said ‘Please let us in lady, all we want is a little food’,” she recounted.

“I had a premonition not to open the back door. I realised straight away that the two men were the two escapees,” she said.

“They must have been waiting near the house for my son and husband to leave. As I rushed from the bathroom I called out that I would get my husband.”

Grabbing a rifle but unable to load it because of her trembling hands, the woman waited in silence before finally realising the men had realised there was no free breakfast on the menu.

“I’ve never been so scared in all my life. I’m still shaking, I hope nothing like this ever happens again,” she said.

The aborted brekky run immediately saw the cavalry of cops storming towards the Summertown area.

Led by detectives from the Armed Offenders Squad, the police contingent featured sniffer dogs and an arsenal of firepower including sub-machine guns, rifles and pistols.

But again, the jailbirds eluded detection, ramping up the urgency, frustration and desperation of the manhunt co-ordinators.

In State Parliament, then Attorney-General Len King took his turn at defending what increasingly became the obviously indefensible.

Mr King highlighted the fraught balancing act between the fledgling concept of rehabilitation and the safety of the public if prisoners chose to abuse the trust shown in them.

In less-than startling revelations, Mr King told Parliament that it would not be possible to allow crowds into Yatala to watch puppet shows and that allowing inmates leave passes heightened the risk of escape.

“In hindsight, it is clear that in spite of the apparently excellent response of these two prisoners to the treatment being received, they apparently decided to make this escape when an appropriate moment arose,” he said.

“In this sense, it must be admitted that a mistake was made.”

In an editorial column, The Advertiser poured scorn on the perceived “can’t win them all” attitude of prison authorities, describing the government as “naive if it expects the public to tolerate the apparent shrugging off of this affair”.

It’s possible the sighs of relief could be heard around the halls of Parliament and police headquarters on Thursday, September 13 when Farnsworth and MacDonald wandered into a city station to hand themselves in.

Tired and desperately hungry after five days without food, Farnsworth then revealed their disappearing act was his novel way of proving a point — that inmates were capable of being among the community without hurting or stealing from people.

They also revealed that after leaving the show, they caught a taxi to Waterfall Gully in the eastern suburbs.

A teenage girl, Wendy, pulled over and offered the two hitchhikers a lift to Toorak Gardens, where another woman picked them up and drove them to their hide-out in the hills.

Wendy realised the hitchhikers were the wanted men, but said she was never in fear and formed a curious friendship with the younger MacDonald.

MacDonald was just 17 when he confessed to the shooting murder of 45-year old Raymond Dunn at Yaninee on Yorke Peninsula in July 1970.

As a youth, he was detained at Her Majesty’s pleasure, and later failed in a court bid to have his case reopened on the grounds he was railroaded into confessing.

Despite his Royal Show escape, MacDonald soon won over the trust of his captors and by June 1976, he again did the bolt while on a leave pass to pick up supplies for the jail canteen.

Police cordoned off the CBD, and also went to the home of university student Wendy, aware that she and MacDonald had become pen friends and that she had visited him in jail.

As they spoke, the phone rang. It was MacDonald, confused and seeking reassurance from the younger woman.

“He was worried and very, very lonely,” she said.

“It was just a friendly call — he wanted someone to talk to. He was worried and was not sure what to do.”

MacDonald’s twisted logic for escaping a second time included being disgruntled that Farnsworth had been parole and deported back to New Zealand in 1975, and the stress of a looming parole hearing which could have seen him released.

“He was afraid (the parole application) would take months for a decision. The impression I got was that he feels everyone was against him,” Wendy said.

“I suggested he go back (to jail) because it would be worse for him if he stayed out.”

The next day, a throng of armed police swooped on the Seacliff Hotel in Adelaide’s south, where MacDonald was waiting to be picked up in a car.

He surrendered without incident, heading back yet again to Yatala and his eventual release.

In echoes of 1973, the public mea culpa was again left in the long-suffering hands of Mr L Gard.

Mr Gard’s exasperated explanation was also eerily similar to the Royal Show debacle — and had to fess up that he personally signed off on MacDonald’s trusted status.

“I approved that recommendation. Everybody can have wisdom in hindsight when the prisoner escapes,” Mr Gard said.

“But nobody recognises the thousands of decisions (we) make which turn out to be correct.”

Well, you can’t win ‘em all, can you Mr Gard?

The lie that cost underworld figure his life

When Carl Williams lied about Michael Marshall’s involvement in a contract killing, he as good as signed the hotdog salesman’s death warrant.

Lunchtime jewel heist which rocked Sydney’s CBD

In what was considered the biggest jewellery heist of the first half of the 20th century, in 1947 a thief managed to steal jewels worth about $600k today. But his glory was short-lived.