The Courier-Mail’s persistence triggered Fitzgerald Inquiry

In the days when the internet only existed in labs and the mobile phone was years away, a young reporter and good old-fashioned journalism exposed Brisbane’s “Sin Triangle” and led to the landmark Fitzergerald Inquiry, writes Greg Chamberlin.

Our Criminal History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Our Criminal History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A BUS ride and an old-fashioned footslogging by a young journalist triggered the work that led to the Fitzgerald corruption inquiry.

It was December 1986, an era when reporters had notebooks, “beep” pagers but no mobile phones, no email or Google.

The Courier-Mail’s chief-of-staff, Bob Gordon, back in Queensland after many years interstate, suggested that a reporter be assigned to find who owned the wedge of real estate at the top of Fortitude Valley that apparently housed brothels and massage parlours.

He dubbed it “Sin Triangle”.

From the office bus one afternoon he was shocked to see girls in an upstairs window flashing their wares. Students from nearby All Hallows’ School had to pass this way.

I was acting editor at the time – the Christmas/New Year period when government and business traditionally take a break and newspapers strive to maintain reader interest.

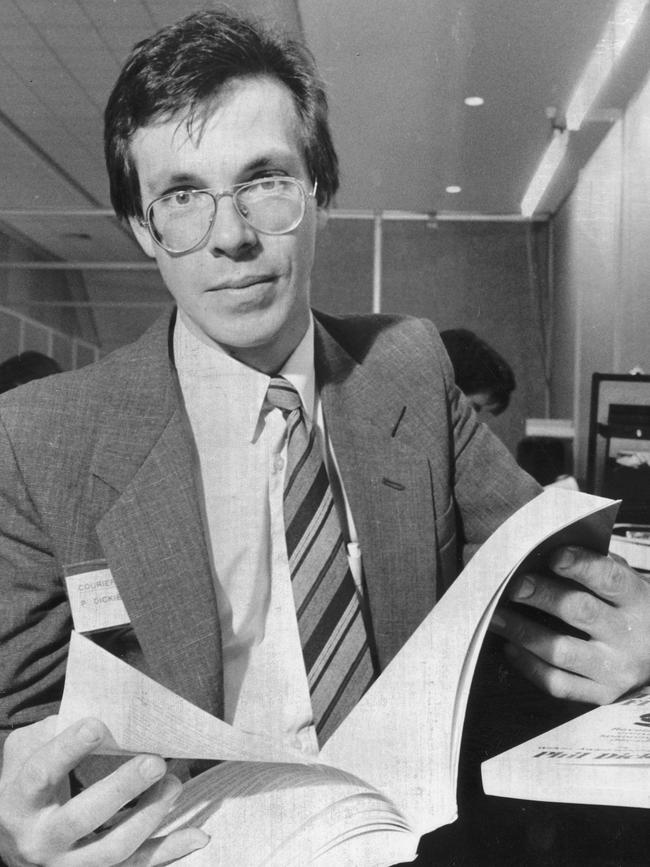

Phil Dickie was assigned to uncover ownership details after two other reporters had failed; one had received an unpleasant threat.

He had recently transferred from The Sunday Mail, where he wrote about motorcycles as well as news stories that included a focus on the seedier side of the Valley.

The Courier-Mail’s media lawyer, Doug Spence, phoned me after reading the draft of Dickie’s article – a who’s who of organised vice operating in the city unchallenged by police.

He had concerns that good faith tests alone would not save the newspaper from legal action, and set out guidelines including documentary evidence if reporters were to pursue this work.

Stopper writs, often financed by the public purse, were the bane of media life in the 1980s. The Courier-Mail had been on the receiving end more than once.

The first of Dickie’s reports was published on the front page on January 12, 1987.

It did not identify him as the author but it was an understatement to say it caused a storm.

For the first time, it identified who was controlling the brothel industry in Brisbane.

It attracted threats, denials, and official claims that only 14 massage parlours operated in Queensland but no evidence that prostitutes worked in them.

It also drew the attention of former police officer Nigel Powell, disillusioned with his experiences in the licensing branch where superiors had thwarted his pursuit of crime syndicate boss Hector Hapeta.

Six weeks after his article, Dickie took a researcher and producer from the ABC Four Corners program on a tour of the seedier side of the city.

Dickie’s work gathered pace. Although he often rode his bicycle into the Valley, he sometimes took a small manual office car. He was taking great risks.

Powell began showing him safer and less obvious methods of surveillance than parking across the road from his target establishment. Powell also began working with Four Corners.

By this time I had become editor and The Courier-Mail’s new owner Rupert Murdoch had taken an interest in the story. He maintained his support despite a growing number of writs.

One was from assistant police commissioner Graeme Parker, to whom Queensland Newspapers had previously paid out over a report about the police licensing branch.

The new writ was in response to written questions Dickie sent to police headquarters on April 23.

These had been legalled by Spence and were intended to be asked sequentially, face-to-face.

Dickie put them in a cab to the police media unit and, unfortunately we believed, it was too late to retrieve them.

The next day, on the advice of police commissioner Terry Lewis, Parker issued a writ against The Courier-Mail.

Then police minister and acting premier in the absence of Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen, Bill Gunn, had been reading Dickie’s work with concern.

At a private function he repeated to me a complaint he had made to the newsroom; he did not propose to be “interrogated” by a reporter about matters he felt should be handled by police.

When I explained that Dickie had been attempting to gain answers through police channels without success Gunn said: “You send me the questions, and I’ll get you the answers.”

A response arrived in the first week of May. Parker claimed he could not answer many of the questions because (as a consequence of his writ) the matters were subjudice.

On May 11, six months after Dickie began his work, Chris Masters and the Four Corners team showed sensational footage of Brisbane’s crime-side in a program entitled The Moonlight State.

It was enough to tip the scales as far as Gunn was concerned; he announced a judicial inquiry the following day.

Dickie received journalism’s highest accolade for his work, the Gold Walkley.

His bestselling book, The Road to Fitzgerald, is required reading on investigative journalism.

The Queensland Government honoured him on Queensland Day 2017 for his contribution to State development and history by making him a Queensland Great.

By the time Tony Fitzgerald began his public hearings on July 27 The Courier-Mail had 17 writs.

All dissipated as widespread corruption was exposed to public view. And an age of accountability began in Queensland in the wake of Fitzgerald’s cleansing process.

Greg Chamberlin was editor of The Courier-Mail in the Fitzgerald years.

Originally published as The Courier-Mail’s persistence triggered Fitzgerald Inquiry