Minister for Murder: MP Thomas Ley convicted of killing a rival and may have killed three others

HE was for a while one of the nation’s most promising politicians but Thomas Ley’s fall was dramatic and would end with him convicted of murder, sentenced to hang, and die alone in a lunatic asylum.

Our Criminal History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Our Criminal History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

HE was for a while one of the nation’s most promising politicians but Thomas Ley’s fall was dramatic and would end with him convicted of murder, sentenced to hang, and die alone in a lunatic asylum.

Known as the “Minister for Murder” when he was NSW’s Minister for Justice in the 1920s because of his habit of knocking back appeals for clemency, Ley’s rise was dramatic.

His subsequent fall was spectacular.

His career was dogged by controversy, with allegations of bribery, corruption and even murder. Three men known to be his rivals all died in suspicious circumstances.

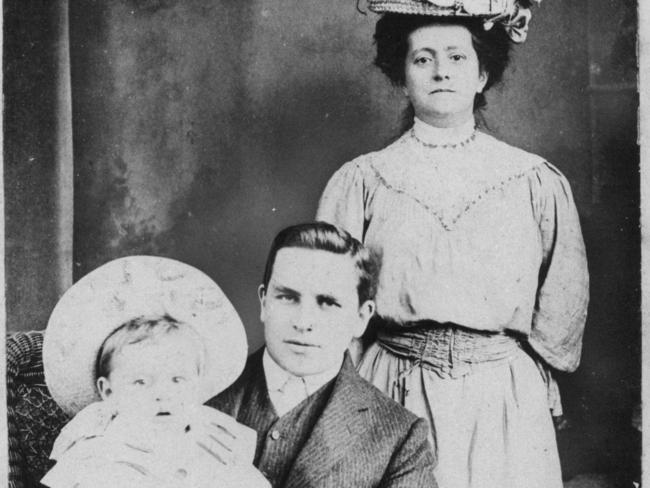

Ley was born in Bath, England, in 1880, the son of a butler. His father died in 1882 and in 1886 Ley’s mother, Elizabeth, took her four children to Australia to seek a better life.

Settling in Sydney, Ley went to Crown St Public School but left at 10 to work in his mother’s grocery store and then on a dairy farm.

Later he sold newspapers and ran messages, but he had loftier ambitions. He was interested in politics from an early age, reading verbatim accounts of Hansard in the paper and even sitting in the gallery at Parliament House to hear politicians speak, dreaming of power. Knowing law was a key to political success, he took a job as a clerk at a stenographer’s office in Pitt St, studying law at night.

In 1898 he married Emily Louisa Vernon, daughter of a wealthy doctor.

In 1907 he dipped his toe into politics by moving to Hurstville and getting elected as a councillor. In 1914 he was admitted as a solicitor, but had trouble moving up the political ladder, failing to gain election as mayor of Hurstville.

Realising he couldn’t move in a straight line upwards, he found a crooked path instead. Aligning himself with the Temperance League, earning the nickname “Lemonade Ley”, the anti-alcohol campaigners helped get him elected to state parliament in 1917 as a National Party member for Hurstville. However, he had no intentions of passing legislation to ban alcohol, as he was taking bribes from brewing lobbyists.

He joined the Progressive Party in 1919, when it split from the Nationals and in 1920 was elected Progressive member for St George. In 1921 when Progressive leader George Fuller passed a no-confidence motion against premier James Dooley and formed a government, Ley had his first very brief taste of a ministry. It only lasted seven hours before Dooley won a no-confidence motion to oust Fuller.

When the Progressives rejoined the Nationals in 1922 Ley became minister of justice. He showed a fondness for the death penalty and notoriously rejected the 1924 appeal of Edward Williams, a poor music teacher condemned to death for murdering his three daughters, despite pleas from the public and evidence that Williams was insane.

As Ley’s lying and hypocrisy became increasingly evident, especially to those within his own party, he switched to federal politics and was elected the member for Barton in 1925.

But the man he beat, Labor MP Fred McDonald, accused Ley of trying to bribe him to win the election.

McDonald was more than Ley’s political opponent, he was also a friend and a legal client but he disappeared in mysterious circumstances before he could prove Ley’s bribery attempt.

His body was never found, but a forged suicide note suggested he had been murdered.

Few believed Ley to be innocent in the matter. He was also reviled as a shonky operator in private business dealings, such as when his company, which manufactured a poison to destroy prickly pear, collapsed leaving investors out of pocket.

In 1928, one of Ley’s business partners, Hyman Goldstein, criticised Ley’s businesses and was later found dead at the bottom of a cliff in Coogee with his hands tied together.

Another of Ley’s opponents, but a one-time associate, Keith Greedor, was appointed by a group of businessmen to investigate Ley’s business dealings, but he, too, died — drowning after falling out of a boat en route to Newcastle.

Rumours about Ley’s dishonesty saw him ejected from office at the 1928 election. He went back to England with his mistress Maggie Brook (who he had met in 1922 and whose husband had died mysteriously shortly thereafter).

In England, Ley picked up where he left off, with suspect ventures including a fake £1 million sweepstakes and black marketeering during WWII.

However, like a modern-day Macbeth, his crimes began to weigh on his conscience and he became increasingly paranoid. Convinced that Maggie was having an affair with barman John Mudie, Ley told two of his associates that Mudie was blackmailing him and they helped abduct, torture and murder Mudie in 1946, dumping his body in a chalkpit.

Ley was found guilty of the “Chalkpit Murder,” but successfully appealed his death sentence.

He was sent to Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum, where he died of a cerebral haemorrhage in 1947.

Originally published as Minister for Murder: MP Thomas Ley convicted of killing a rival and may have killed three others