How to get away with outback murder

An author’s bid to devise the perfect murder provided the real-life technique for disposing of three slain Australian men in the 1920s and 1930s, and perhaps a fourth ten years later — but the killers missed a crucial step.

Our Criminal History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Our Criminal History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Australian novelist Arthur Upfield’s quest for the perfect crime was the inspiration for three brutal murders in Western Australia in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Was his plot also responsible for one of Queensland’s most celebrated murders a decade later?

Upfield was working on the rabbit-proof fence in 1929, struggling with what became the Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte adventure book The Sands of Windee and stuck on how to dispose of a body.

True Crime Australia: Who killed granny stuffed in barrel?

High security: Sadistic jail rivals back together

A workmate came up with the idea of burning the victim’s body along with that of a large animal, pounding the bones to dust, casting the lot to the wind, sifting any metal out of the ashes and dissolving it in acid.

It became quite the topic of campfire conversation and one of those who joined in was itinerant stockman Snowy Rowles.

Rowles used the idea to dispose of three men — James Ryan, George Lloyd and Louis Carron — and steal their possessions.

It worked perfectly on Ryan and Lloyd but he made the mistake of leaving Carron’s wedding ring to be found by police who were on a missing person quest.

That, plus Upfield’s evidence, led Rowles to the gallows, a story related in the ABC telemovie 3 Acts of Murder.

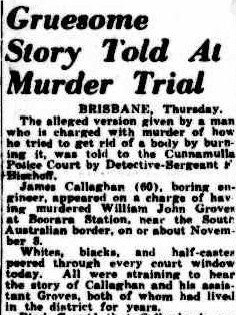

Fast forward to November 1940 and Queensland police were told of the disappearance of William Groves, 60, a well-sinker’s labourer, from Boorara Station, 390km from Charleville.

Groves was reported missing when James Cotter, the station overseer, unexpectedly dropped into the lonely camp where he was working for James Callaghan.

“Where’s old Bill?’’ inquired Cotter.

“Oh, he’s gone away to Charleville,’’ was Callaghan’s reply. “I paid him off and he went off with a couple of chaps in a truck.’’

Boorara manager Arthur Seal thought it odd because he knew that Callaghan was strapped for cash and could hardly afford the £160 ($12,000) he owed his labourer.

Police from Eulo were called in and became suspicious but ran into the dead-end of Callaghan’s bland assurances.

They called in the heavy brigade from Brisbane in the form of Detective Sergeant Frank Bischof (later to be commissioner and godfather of police corruption) and Detective Jack Mahoney.

They knew something was fishy because all Groves’ effects had been found at the camp so they made the two-day trip to Boorara where police had set up a camp — “heat, flies and whirlwinds’’ — where the temperatures topped 47C in the shade and there had been no rain for two years.

Callaghan couldn’t be shaken, but suspicion deepened when police found that he was in deep financial strife and was being sued by his wife for maintenance. A few hundred metres from the camp they found the remains of a big fire and, sifting through the ashes, came across some charred buttons. Attention then turned to the 140m borehole shaft, from which police had been getting their drinking water.

Despite objections, and sabotage attempts by Callaghan, they managed to start the engine to pump out the well.

The first time the pump was pulled from the hole it contained small pieces of bone, a tooth and some charcoal. Next came up more finely broken bone and a charred trouser button.

“Police,’’ it was later reported in The Sunday Mail, “turned around to find an ashen-faced Callaghan backing away.’’

It was all over as he confessed that he had accidentally killed Groves in a fight, burnt his body on a 1m heap of dry mulga for five hours, raked out and pounded the bones and dumped them into the borehole.

Bischof and his team weren’t buying the accident story and reckoned he had murdered Groves because he couldn’t pay his wages.

Callaghan was charged with murder, convicted and sentenced to life in prison, where he died in 1952.

We will never know if Callaghan read The Sands of Windee but he made the same careless mistake that helped Inspector Bonaparte crack the perfect murder.

• This is an edited version of a story first published in August 2013

Originally published as How to get away with outback murder