How an unusual diamond ring helped police solve grisly Melbourne murder

When a woman was found horribly murdered in the bedroom of her ransacked Melbourne home, it was an unusual item of jewellery that led police to her killers.

Our Criminal History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Our Criminal History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In the early morning of December 1, 1856, a police constable named Matthews creaked open the door to Sophia Lewis’ bedroom.

Her house on Stephen St, later to be named Exhibition St in Melbourne, had been ransacked and drawers were strewn across the floor.

An alarm raised by a neighbour had led Matthews through the open front door, through the trashed living room, where Sophia was known to entertain local men at night.

The house had a bad reputation.

Now, Lewis was lying in her bed.

Her throat had been cut from ear to ear and the sheets were soaked with blood.

The cut was so deep that her head was barely clinging to her neck.

The bedroom, too, had been turned upside down by whoever had committed this ghastly murder.

Although Matthews didn’t know it, the stolen items included a precious ring in the shape of a snake, encrusted with diamonds.

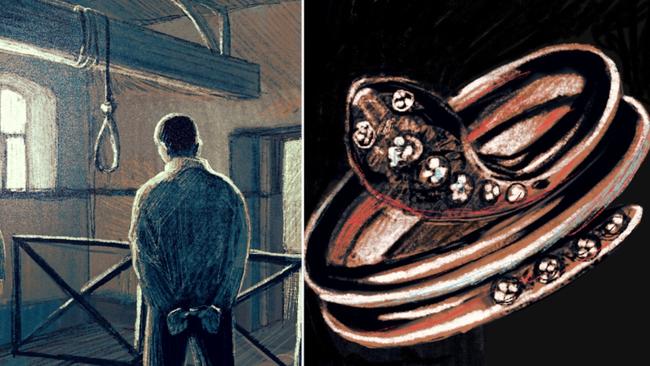

The jewellery would prove crucial in tracking down two violent men who met their own grisly fate at the hangman’s noose when they were found guilty of Sophia Lewis’ murder.

THE SNAKE AND SUPPER FOR THREE

A wide police investigation spanning much of the colony ensued as word of the murder spread.

Friends of the victim remembered a few remarkable pieces of jewellery that had belonged to her, including a bracelet and a snake ring with diamonds.

The ring was found by police in the possession of a Chinese man named Tang Lin.

But he could prove he had recently bought it from another Chinese man, Chong Sigh. Sigh was known to visit Sophia Lewis’ house of ill repute.

And when police tracked down his associate Hing Tzan, they found in his tent a bracelet that had belonged to Lewis.

Jane Judge, a friend of the victim, recognised the items instantly.

At about 5pm on November 30, just hours before the murder, Judge recalled the snake ring being on the victim’s finger.

The Collins St jeweller who made the ring also confirmed the item was the exact one that had belonged to Sophia Lewis.

In addition to the ring evidence was testimony from a sailor, William Harper, who lived close by and saw Chong Sigh and Hing Tzan in Sophia Lewis’ backyard hours before the murder.

But the evidence wasn’t entirely clear cut.

Problems with Chinese interpreters frustrated both sides of the case and a confession made by Tzan that implicated others had been recounted.

Tzan had attempted to shift blame to two men named Ah Loo and Ah Ping, saying they had also visited Lewis’ home that night.

But among other evidence from Constable Matthews was that the supper table had been set for three people.

Plates had been used by three and glasses had been poured for three, suggesting Lewis had dined with Sigh and Tzan only.

It was supposed that Tzan was desperate to implicate Ah Loo because it was likely he had provided information to the police about the case.

Jane Judge also claimed Ah Loo and Ah Ping were not seen at the house around the time of the murder, but the two accused were spotted.

The Crown arrived at a shaky series of events, later reported in newspapers.

Sigh was the first to cut Lewis’ throat as she lay passed out drunk in her bed.

But when she started to move, Tzan took up the blade and made no mistake about her demise by so severely cutting her neck, she was nearly decapitated.

That was the account that seems to have seen both men condemned by the court.

They were sentenced to hang.

LAST-MINUTE PLEA

One report from 1857 suggests the men refuted their guilt at the eleventh hour.

In interpreted conversations with prison authorities in Melbourne Gaol on the night before they were scheduled to be hanged, Sigh continued to claim ignorance of the crime and denied any involvement.

Tzan again attempted to shift the blame, this time entirely to Ah Ping, who he said came up with the idea of getting Lewis drunk and ransacking her house.

Tzan claimed he saw Ah Ping take a razor, roll it in paper and stow it in his pocket.

He claimed that while a group of men, not including Sigh, robbed the house, Ah Ping was the only one who entered the bedroom where Lewis was sleeping.

Although no sound was heard, Tzan claimed Ah Ping must have carried out the murder silently.

Tzan claimed he was then handed a parcel of stolen goods, which Ah Ping had stolen from the dead woman’s room.

The last-minute testimony failed to help the doomed pair.

On Wednesday September 2, 1857, they were taken from their cells after a sleepless night.

Reports say they were weak and almost paralysed with fear.

Tzan spoke in rapid murmurs and refused to let authorities interfere with a cloth he had tied around his head.

Sigh said nothing, but cried all the way from his cell to the noose.

He was the heavier of the two, standing almost two metres tall.

On this particular morning, the regular hangman was away.

MORE TRUE CRIME:

CARL’S DEATH REVEALED BY EDDIE MCGUIRE

Instead prison authorities recruited a prisoner to do the deed.

It would later be said he carried out the duty with as much coolness and proficiency as if he had done it before.

When Sigh was hanged, his incredible weight almost broke the rope.

When Tzan was executed, a mask of his face made shortly after death was remarked upon by prison guards for resembling another murderer who had been hanged not long before.

Hing Tzan and Chong Sigh became the 52nd and 53rd prisoners to be executed in Victoria.

After a routine inspection, their bodies were carted from the gaol and buried unceremoniously in a plot reserved for murderers.

Originally published as How an unusual diamond ring helped police solve grisly Melbourne murder