Aussie convict link to key moment in world history

HOUSEMAID Rachel Turner was transported on a “floating brothel” for theft — but in an extraordinary turn of events the convict’s illegitimate son would be the only Australian to fight in the Battle of Waterloo.

Our Criminal History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Our Criminal History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A CONVICT girl made good, reunited after three decades with the bastard son taken from her and shipped across the globe as a tot — a boy who became the only Australian present at one of history’s key battles, a clash that would decide the fate of the world.

The story of Rachel Turner — transported on a “floating brothel” from England to Sydney — and her son Andrew White, a young officer at the Battle of Waterloo, is extraordinary, tear-jerking and uplifting all at once.

It begins in the harsh courts of Middlesex in 1787’s England, where young housemaid Rachel is convicted of stealing household goods from her employer. Despite her protesting that she was duped into confessing, the 25-year-old is sentenced to seven years’ transportation.

The nightmare begins immediately. Her transport is the Second Fleet ship Lady Juliana; her convict companions 226 women, most of them London prostitutes; and her “hosts” a corrupt crew who use the women for their own desires and pimp them out to hundreds of men on extended stops at ports across the world. A floating brothel.

The Juliana’s 309-day voyage to Australia is one of the slowest on record, largely because of these stops (by comparison the First Fleet took 252 days). It is not clear if the women — described harshly as unruly, boozy and violent — share the profits, or are simply sex slaves, but it must have been horrific.

Our criminal history: How book plot inspired outback slayings

Last man hanged: From petty crim to jailbreak killer

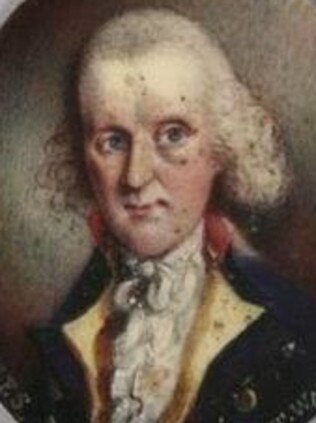

How Rachel copes is not recorded; but sometime after her arrival in 1790 she finds herself assigned to the household of Dr John White, the chief surgeon who had come out with the First Fleet.

She becomes his housekeeper … and his mistress; and in 1793 she delivers his son, Andrew Douglas White.

But life is hard. A year after the birth, White — ground down by six gruelling years in the colonies — goes home. He does not take his convict concubine — but he does want their illegitimate son. It is not clear whether he takes the baby or has him shipped a few months or years later; but whichever, Rachel is parted from her son, a young boy is sent on a bewildering voyage across the world without his mother, and she must face the strong probability of never seeing him again.

Ten thousand miles from his mother, young Andrew is raised by the sister of one of his father’s military friends. His dad, meanwhile, marries a “suitable” lady and has three more children. Andrew is not denied opportunity, however — he joins the army, entering the Royal Engineers as a junior officer in 1812.

It is the height of the Napoleonic Wars, which have been setting the continent ablaze for years as a small, tough Corsican with his French Grande Armee bends Europe to his will.

In June 1815 comes the final act, the ultimate showdown: The Battle of Waterloo, where in the Belgian countryside Napoleon faces the British army commanded by Lord Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, and his Prussian allies.

And that’s where Andrew White’s extraordinary personal tale intersects with Big History. As a first lieutenant, he is one of the junior officers on the Engineers’ staff: a job that will likely involve a lot of galloping about the confused battlefield, ferrying orders while dodging artillery fire, musketry and charges by the French cavalry that infamously cut right through the British lines, forcing even the Duke himself to seek safety inside bayonet-bristling “squares” of infantry.

Tens of thousands are killed and wounded as Napoleon is narrowly defeated. Not Andrew, who serves in now-peaceful Europe a while longer then returns to England, where he receives his Waterloo medal.

Follow: True Crime Australia on Facebook and Twitter

Then the story gets personal again. Seven years after the battle, Andrew heads back to Sydney to take up his father’s property — where, against the odds, he is reunited with his mother.

The woman he finds is no disgraced house servant; his mother is now the highly respectable Mrs Thomas Moore.

Rachel married sailor, ship builder and landowner — and in time, philanthropist — Thomas Moore in 1797; by the time Andrew arrives they live, in the words of former National Portrait Gallery Director Angus Trumble, “in prosperous and eminently respectable retirement at Moorebank, a handsome tract of land near Liverpool, New South Wales — thoroughly cleansed of the stain of penal servitude.”

After two years, in 1824, Andrew returns to England and promotion to second captain, finally coming back to Sydney in 1833 — a year after his father’s death, aged 75. He weds Mary Anne MacKenzie at St John’s, Parramatta in June 1835.

Once again, fate steps in. Just two years later Andrew dies of unknown causes, childless, on 24th November, 1837. His mother is said to have treasured his Waterloo medal after his death — until her own passing, just a year later, aged 75.

With no children of their own, her widower Thomas Moore leaves everything to the church for the establishment of what becomes Sydney’s Moore Theological College — and St. Andrew’s Cathedral.

Moore has a marble wall monument — the only known image of her — dedicated to his wife in St. Luke’s Church, Liverpool. And there we turn to the expert, Angus Trumble: “That tablet is a remarkable rarity for it carries her bas-relief profile portrait, stiff and pastry-ish, certainly, but dignified, alert, even spry. She wears her hair in the mode suddenly brought into vogue upon the accession of Queen Victoria barely two years prior.”

What a family. What a story. Rachel’s journey would have broken so many, but not her. Her son, though his passing went unremarked, has a very real place in history. And by blood, birth and marriage they are embedded in the story of Australia.

The final words belong to the inscription on Rachel’s monument.

“She was the most affectionate, and virtuous wife, a tender mother, and ever kind to the poor. She was united to her husband for 42 years, during which time, she was a constant attendant at the house of God, and a strict observer of family prayer, and died in peace.”

Originally published as Aussie convict link to key moment in world history