THE callout had seemed, to the two South Australia Police patrol officers, a simple enough request — instead, the duo found themselves in the crosshairs of one of Australia’s most successful bank robbers.

A man wearing a dark jacket, wraparound sunglasses and a cap had been seen for the past few days sitting on a park bench at the War Memorial on Port Rd, Hindmarsh.

The officers, Senior Constables Malcolm Racz and Constable Matthew De Sira, had been tasked to find out why.

What they could not have known was this mundane job would place their lives in danger.

But that violent, terrifying incident would also spark one of the best examples of good, old-fashioned detective work.

The hail of bullets would expose a trail of evidence leading to overseas drug runners, international stolen motor vehicle scams, false identities and a toddler who died in 1951.

Detectives would have to follow a paper trail across Australia — and personally search 25,000 post-office boxes across metropolitan Adelaide — in order to get their man.

And while all their efforts laid the groundwork for Harry Richard Nylander’s downfall, it was the armed robber who hammered the final nail into his own coffin.

For all his deception, all his careful planning, Nylander’s arrogant pride in his skills with a handgun sealed his fate.

“THIS HAS GONE REALLY BAD”

At 2.30pm on August 16, 2000, Racz and De Sira were tasked with a code 404 — SA Police code for “suspect loitering”.

The mysterious man seemed surprised — and nervous — when the officers approached him that afternoon.

They noticed the palms of his hands and undersides of his fingers had been covered in neatly-trimmed, skin-coloured adhesive tape.

De Sira saw a bulge in the back of the man’s jacket at the waist.

“I wasn’t expecting it to be a handgun — a lot of people carry their mobile phones on their hips, and it was consistent with that,” he told the SA Police Journal in 2003.

“Whether it was something actually causing it to bulge, or just a fold in the material, I wasn’t sure.”

The man told the officers he was Graham John Palmer, that he was born in 1948, and that he lived in Woodville.

Palmer explained he was waiting for a friend and that he taped his hands because he played handball — a curious explanation, but one that could not be discounted.

Racz and De Sira did a background check on Palmer and, although it came up negative, decided to hang around and keep an eye on him.

“I couldn’t really pick anything that I could see was definitely wrong, and you can’t just search people in the middle of Port Rd on a whim,” Racz told the Journal in 2003.

Palmer was not interested in hanging around — he walked across Port Rd and behind a complex which contained branches of Westpac Bank and the State Bank.

Police instincts kicked in and, expressing their shared certainty something was amiss, Racz and De Sira followed in their patrol car.

They next saw Palmer driving a blue Nissan Pulsar sedan — and when he saw them, Palmer accelerated away quickly.

“I just looked at him and said ‘that’s him’,” De Sira remembered.

“He’d taken his hat off, but still had the sunglasses on … you could see his eyes, they were wider than the sunglasses, like ‘oh, shit, the police’.”

The duo gave chase through the narrow backstreets of Brompton, with Palmer braking late and then speeding out of the corners.

The pursuit ended in a cul-de-sac in Brompton, called Pens Close.

The officers pulled into the side street and found their suspect crouching behind his car, which was parked in the middle of the road.

“He was looking back at us and I thought ‘oh no, this has gone really bad … something’s happening here’,” De Sira said.

THE PENS CLOSE CUL-DE-SAC IN 2015

As the partners got out of their car, they saw Palmer stand up, raise a semiautomatic pistol, take aim and fire at Racz from about 10m away.

De Sira reacted instantly.

“I just saw the gun and it was pointing towards Malcolm, so I thought ‘I’ve got no choice, I’ve just got to draw my firearm and do what I’m trained to do’,” he said.

“I just dropped my keys on the roadway, pulled my gun out and took my shots at him.

“There was no time to challenge him because he’d already overstepped that point … it was just a case of ‘pull the gun out and instinctively fire some shots to stop him’.”

Racz had been caught off-guard by Palmer’s attack.

“I hopped out of the car, shut the door and he was at the back corner of his car (with) this firearm pointed straight at me,” he said.

“That’s the first thing I saw, and it immediately discharged.

“I thought ‘s**t, what the hell is going on?’ and, there’s been this exchange of fire, because I heard the bangs.

“Then, my thought was ‘get straight round to the back of the police car and draw the gun’.

“It took a split second … for a moment there I was, like, hanging out on the clothesline — high and dry.”

DEAD STILL

Fortunately, Palmer’s shots did not strike Racz — but De Sira was right on target.

One of his rounds appeared to hit the gunman in the chest area, prompting not a spray of blood but, curiously, a puff of green mist.

It was of little comfort to De Sira, for he could neither see nor hear his partner.

After radioing for back-up, he moved toward the back of the patrol car and yelled out to Racz — who heard him, fortunately, and each officer realised the other was unharmed.

But, possibly, not for long.

Palmer returned fire and again ducked behind his vehicle, but his gun appeared to be jamming.

Quickly assessing the risk, De Sira opted to crawl toward the front of the patrol car for a clear shot at their assailant.

“My life did flash before me, I thought about my wife and children,” he said.

“I was also thinking ‘there’s no way I’m going to die here today on this bit of lawn, there’s no way this is going to be the end of it for me’.”

Grimly determined, he carefully looked up over the car — Palmer was reloading his weapon.

“Throw your weapon away and come out from the car,” De Sira yelled.

Suddenly, the gunman gave ground — not to surrender, but to crouch-walk backwards up the driveway of a house, his gun drawn and his steady gaze fixed on De Sira and Racz.

Neither officer dropped their guard.

“We were able to take a shot at him if we wanted to, but he’d backed up towards the front door of a house and there were windows there,” De Sira said.

“The chances were a bullet could have gone astray — I wouldn’t want to hurt anyone who was just in their home watching television.”

Later, De Sira would be surprised by his composure amid the tension.

“I expected the barrel of my gun to be jumping all around the place and yet it was dead still,” he recalled.

“I think it was very much that your senses all drop, you only use the sense of sight.

“It’s a bit like tunnel vision — you’re just concentrating so much on him, everything else fades out.”

The duo watched as Palmer reached the house’s side fence and, sparing them but a momentary glance, climbed over it and took off.

They advanced immediately but, even in so short a time, the mystery man had vanished.

Unable to find their suspect, De Sira and Racz began to search his car, finding a small calico bag and three live rounds.

On the road next to the vehicle, they recovered a can of green spray paint — it had been punctured by one of De Sira’s bullets.

KEYS TO A MYSTERY

Understandably, the brazen daylight attack upon two police officers immediately sparked an intense investigation, codenamed Operation Manx.

Investigators under the command of Detective Senior Sergeant Jack Kelso started by going over the scene of the shootout.

They recovered a shirt covered in green paint, suggesting two things — the punctured can had been in Palmer’s pocket, and De Sira’s shots had struck home.

In the abandoned Nissan, officers found a hat and coat, more calico bags and a mask made from a woman’s stocking.

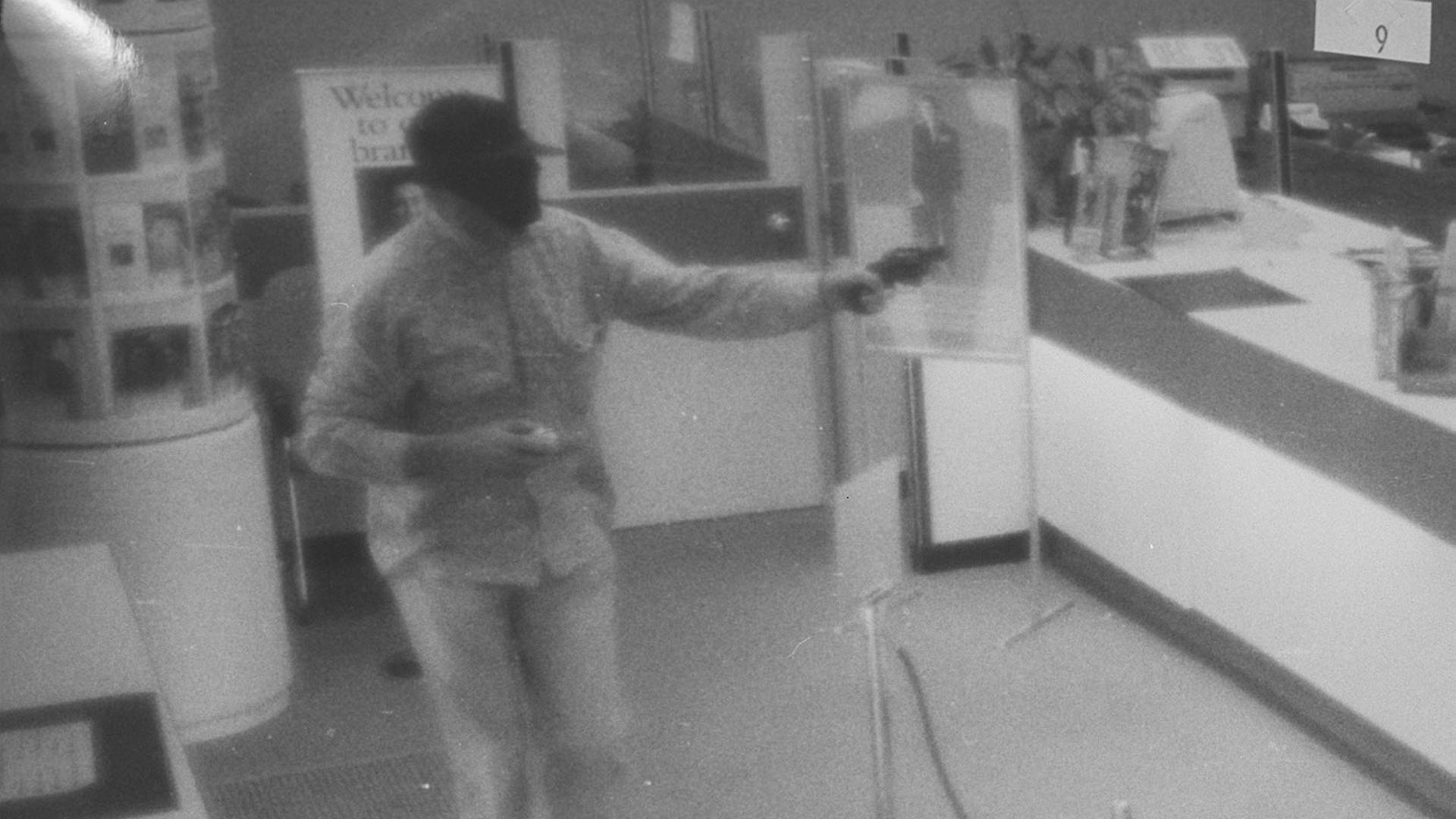

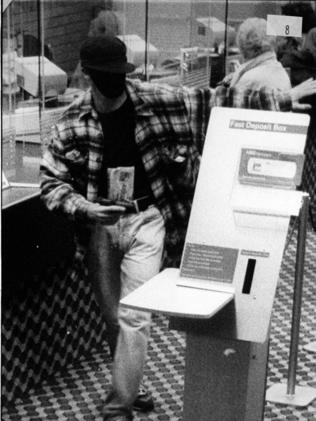

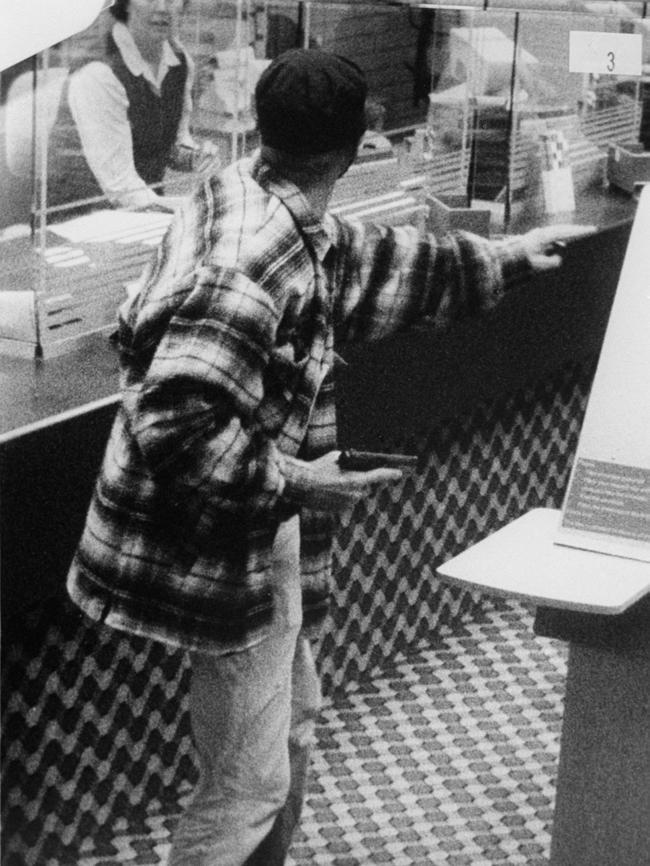

The mask matched that worn by a robber who had stolen more than $30,000 from banks in Kent Town, Wayville and Walkerville between 1996 and 2000.

In each case the robber, armed with a pistol and wearing a similar disguise, used green spray paint to blind security cameras — and netted $31,000 in total.

Importantly, a key wallet was still hanging from the vehicle’s ignition.

It contained some house keys, the key to the Nissan, a key to a Honda sedan and a post-office box key.

As their colleagues investigated, Racz and De Sira faced the emotional fallout.

De Sira managed to sleep, but only after he and his wife talked about the incident until the early hours of the morning.

For Racz, sleep was long time coming.

“I don’t like tossing and turning in bed, so the first night I went and watched a lot of TV,” he said.

“The second night I got an hour or two and, the third night, I had a huge sleep where I just absolutely crashed.”

Both men immediately returned to work and to the scene, where another shock awaited De Sira.

“The ballistics officers pointed out a hole in a neighbouring fence and said ‘that’s his shot at you’,” De Sira remembered.

“I said ‘he was only shooting at Malcolm’ but they said ‘no, he took a shot at you, too’.”

The investigation team now believed they had a serious offender on their hands — all they needed to do was find him.

That was no small task given the name “Graham John Palmer” had already come up blank.

Police checked similar names in all states, in birth and death records and with the Immigration Department.

They liaised with Customs, the Australian Taxation Office, Federal Police, the National Crime Authority, ASIO and even Interpol.

They found nothing.

When Racz and De Sira described the gunman’s firing stance as “military-type”, investigators reached out to all branches of the Defence Force, to no avail.

They doorknocked the Woodville street where “Palmer” had said he lived — to the surprise of absolutely no one, he had lied to Racz and De Sira.

A list of known criminals who had similar offences also turned up nothing.

Graham John Palmer obviously did not exist.

With the gunman at large, Racz and De Sira became extremely conscious of their personal security.

Racz could not visit his local bank without first checking the building and surrounding area.

“I’d wonder ‘is this guy here in the shopping mall at the moment?’,” he said.

De Sira, meanwhile, came to notice every blue Pulsar he passed on the roads.

The 1999 model, investigators learned, had been stolen from an address in Linden Park three months before the shootout.

It had done almost 5000km, averaging 470km a week since it was taken, but was surprisingly well kept and neat.

The Nissan’s key was linked to a scam that operated out of England.

It allowed car thieves to obtain keys from the vehicle’s manufacturer by quoting their vehicle identification number.

The Honda’s key was connected with another stolen car, this time taken from a residence in nearby Heathpool in March 1999.

It would be a third key — which unlocked a suburban post office box — that would give police their first real lead.

A NEEDLE AND A SPOON

Police faced the onerous task of a physical search to find the right box.

Eight officers, each with a copy of the key, searched 25,000 post boxes in 44 post offices before opening No. 68 at a branch on Grange Rd, Findon.

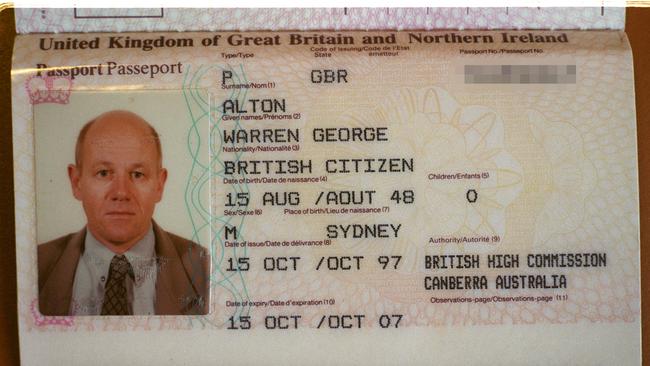

The post box was leased to a man by the name of Warren George Alton and, inside, officers found a letter from the Adelaide Pistol Club to the same name.

There was also a letter from an address in South London.

That letter, from “D” to “W”, contained information relating to the production of false registration labels for the stolen Honda.

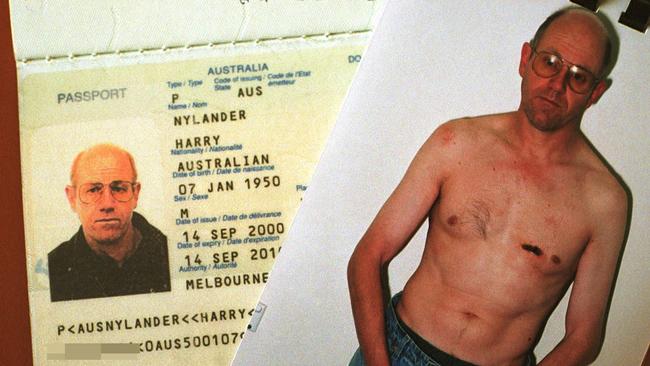

A check on the “Alton” name revealed a driver’s licence, firearms licence and a passport — but there was nothing linked to the name before 1983.

That was because Warren Alton was long dead.

The New South Wales births and deaths registry revealed Alton had been born in May 1948 and died, as a toddler, in March 1951.

The paper trail on Alton led to a Commonwealth Bank account at Burnside, accompanied by security video footage of the supposedly dead man entering the bank.

Armed with Alton’s financial records, police found links to an Englishman called John Dalton, whom they believed to be the label forger.

Dalton, it transpired, was one of 15 aliases for David Arthur McMillan, who had been arrested in Stockholm for possession of 2kg of heroin and had escaped a Thai jail in 1996.

An international fugitive, McMillan still faces the death penalty in Thailand and remains the subject of an Interpol “Red Notice”.

Further checks revealed Alton had sold a firearm six days after the shooting, and had a safe-deposit box in Sydney.

Police even found a Blockbuster video membership, and an address in Woodville and a mobile phone all under Alton’s name.

Crucially, the Burnside bank account had been used to pay for a classified advertisement in The Advertiser for the sale of a vehicle.

That led police to the name of another man, Harry Richard Nylander, who was known to have armed robbery convictions in Western Australia.

He had also served a six-year stint behind bars for a series of armed robberies in Victoria in the 1970s.

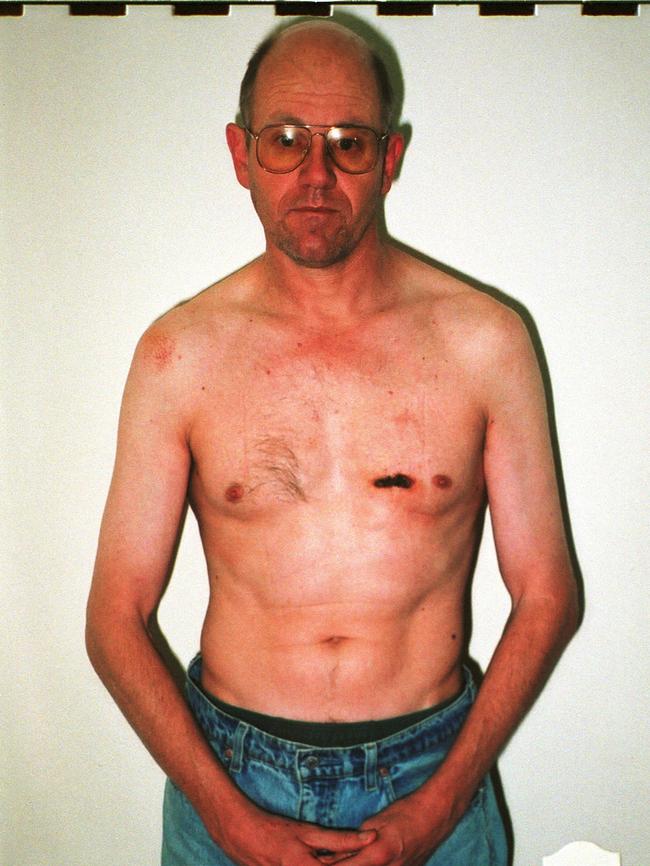

Nylander, they realised, was both Palmer and Alton.

Not only had he had robbed the four banks between 1996 and 2000, he had been casing the Westpac and State Banks when Racz and De Sira spoke to him.

The final piece of the puzzle was a piece of paperwork from the Burnside bank, bearing Alton’s fingerprint — it was a perfect match for Nylander.

Investigators got back on the phone to the Immigration Department, providing a list of all the aliases it had discovered.

On September 9, 2000, Senior Sergeant Kelso received a telephone call from immigration officers.

Earlier that day, Nylander had walked into the department’s Melbourne office to collect his new passport.

Victoria Police’s Special Operations Group were waiting for him, and he had been arrested.

But not even the battle-tested SOG officers were prepared for what Nyland had under his shirt.

The career criminal still had a bullet wound in his chest — from which he had gouged out the fragments of De Sira’s shot with a needle and the handle of a spoon.

TOO GOOD TO MISS

With Nylander in custody, SA Police’s investigation proceeded rapidly.

A search of various related addresses recovered a number of firearms, including a Heckler and Koch 9mm semiautomatic pistol.

The weapon had obviously been used in the shootout — it still had green paint on the handle.

The evidence was mounting up but Nylander was an intensely stubborn individual and insisted on taking the matter to trial.

He pleaded not guilty to having fired on Racz and De Sira with the intent of causing them grievous bodily harm, and denied responsibility for the earlier bank robberies.

It was far from his best idea.

On December 6, 2002, Nylander took the stand in the Supreme Court to give evidence in his own defence.

He was insulted by the accusation he fired at the patrol partners because — as he was at pains to explain — he was simply too good at shooting to have missed them.

In support of his boasting, Nylander and his counsel produced his numerous awards for competitive shooting, including his bronze medal in the so-called prestigious “Steel Gauntlet”.

That event, he said, involved competitors armed with semiautomatic pistols shooting under a time limit to register two hits on each of the human-sized targets in a large range.

Nylander, with no small amount of pride and arrogance, told the jury he had placed third using a normal revolver, which he had to reload himself.

Had he opted for the semiautomatic, he inferred, he would have come home with the gold.

His arrogance was a flaw all-too easily exploited by prosecutor Nic Alexandrides.

With aching politeness, he suggested Nylander was lying — not about the shootout, but about his pistol prowess.

Mr Alexandrides questioned the legitimacy of the record books, of the awards and, most gallingly, of the mighty Steel Gauntlet itself.

Nylander, fairly frothing at the mouth, would not stand for it.

“I’m quite capable of shooting accurately from 50m — I could have shot them from any distance if I’d wanted to,” he barked from the witness box.

“I fired from the ground and I aimed at the first officer’s legs, knowing that I would miss him by at least two feet.

“I chose a distance of two feet because I wanted to shoot in a direction that would discourage him — if I wanted to shoot the police officers, I was more than capable of hitting them.”

Wholly satisfied, Mr Alexandrides took his seat at the bar table while Nylander’s defence counsel, Pat Amey, dropped his head into his hands and groaned softly.

Jurors worked to stifle their laughter as Justice John Perry directed them to find Nylander guilty, by reason of his impromptu confession, of attacking the police officers.

Nylander watched it all uncomprehendingly, finally choking out a confused “what?” as he was led away to the cells.

Jurors had little difficulty convicting him, after that, of the bank robberies as well.

Seeking to salvage something from his client’s mess, Mr Amey urged Justice Perry to take a merciful approach.

There was, he posited, a rational explanation for Nylander’s complex web of identities.

“He used different names once he got out of jail in Victoria in an attempt to have a new start, to start fresh,” he said.

“We urge Your Honour not to put the chance of rehabilitation irretrievably behind him.”

Mr Alexandrides was unmoved, dubbing Nylander a serial bank robber who carefully planned his crimes “with malice” and so had little chance of rehabilitation.

He told the court Nylander had robbed one of his targets — the ANZ branch in Kent Town — twice in four months, leaving staff members traumatised.

“Several of the bank staff refused to give victim impact statements because they did not want to re-live the experience,” he said.

“The shooting at the officers is at least as serious … it’s only by good fortune they were not seriously injured or indeed killed.”

Justice Perry agreed, saying the crimes deserved a head sentence of 48 years — 10 for each robbery and eight for the shooting.

He discounted that sentence to 32 years, because it was too harsh, and set a non-parole period of 24 years.

That penalty was just two years fewer than the term given to “bodies in the barrels” serial killer James Vlassakis, who murdered four people.

Learning he would not be released until 2026, at the age of 77, did not appear to faze Nylander.

He listened, apparently unaffected, as Justice Perry told the robber he had refused to accept responsibility for his actions.

He said that between May, 1996, and May, 2000, Nylander had “carefully planned and executed’’ robberies at Kent Town, Walkerville and Wayville.

“Since then you have shown no expression, no demonstration of concern or remorse for your victims,” Justice Perry said.

“I have been told some of them are not willing to give statements (about the robberies), preferring not to revisit the traumatic ordeal you subjected them to.”

The gunfight with the police, he ruled, was “just as serious”.

PRISONER’S BILE

For Racz and De Sira, it was the end of a long ordeal.

“It’s a very dangerous job and we have to look after police because we do our best to look after the community,” Racz said outside court.

De Sira had found the trial process extremely confronting.

“I gave my evidence and found myself getting emotionally upset and had to stop … it was quite a while before I could actually speak because of holding back tears,” he said.

“When he gave his evidence, I sat there shaking for about 30 minutes because that was the first time I heard him speak.

“My legs, chest and arms … everything was just shaking.

“I was pushing my arms down on my legs to try to stop myself and couldn’t … I think all the emotions that, perhaps, I should have felt on the day, all happened in court.”

His immediate goal, he said, was to move on with his life.

“I don’t want to spend the rest of my life hating him — you end up eating yourself up from inside if you start doing that,” he said.

As De Sira moved on, bile and scorn became Nylander’s primary motivations.

In November 2007 he filed a lawsuit against the SA Government, claiming he contracted hepatitis C from a prison haircut.

He deserved $40,000 compensation, he claimed, owing to the negligence of the government and its employees at the Yatala Labour Prison.

“They failed to ensure that I was properly advised of and trained in the use of hair clippers,” he explained in his statement of claim.

“They also failed to provide cleaning products to sterilise the hair clippers, and so my infection was as a result of the defendant’s negligence.”

The government filed a defence, denying any connection between Nylander’s infection and the clippers and saying he was not entitled to compensation.

Nylander’s suit did not go far — on February 3, 2008, authorities revealed he had died in custody after a long battle with cancer.

In a short statement, Correctional Services chief executive officer Peter Severin said Nylander had died in a hospice after treated in the prison infirmary for “some time’’.

It was the end of an era in Adelaide crime, and — despite himself — De Sira found it left him with unanswered questions.

“If I could have talked to him, I would ask why he did it,” he said.

“Why he decided to stay and fight, and not run.”

(Produced by Paul Purcell)

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Photos show chilling find at US Wieambilla accused’s house

Prosecutors fighting to allow Australian police to give evidence in the upcoming trial of Donald Day, who is linked to the Wieambilla massacre, say the cases have chilling similarities.

Shock link between UK child killer and Aussie bishop stabbing

The teen who murdered three little girls at a Taylor Swift-themed dance class in England had searched for material on the stabbing of a Sydney bishop.