Paddy Moriarty’s disappearance has changed Larrimah forever

A YEAR ago, Paddy Moriarty vanished from the tiny Northern Territory town of Larrimah. His disappearance has changed the town forever

Crime in Focus

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime in Focus. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE late Territory wordsmith Andrew McMillan once wrote that the dozen-odd locals in Larrimah would boast, half-jokingly, their little town wasn’t in the middle of nowhere, it was the “centre of everything”.

McMillan, a true eccentric, died six-and-a-bit years ago and is buried with his typewriters a few clicks out of town, his favourite place, where he used to come to get away from the distractions of Darwin and write.

Even an imagination as colourful as McMillan’s would have struggled to grasp how the disappearance of Paddy Moriarty late last year could thrust the town from obscurity to notoriety, at the centre of a real-life murder mystery.

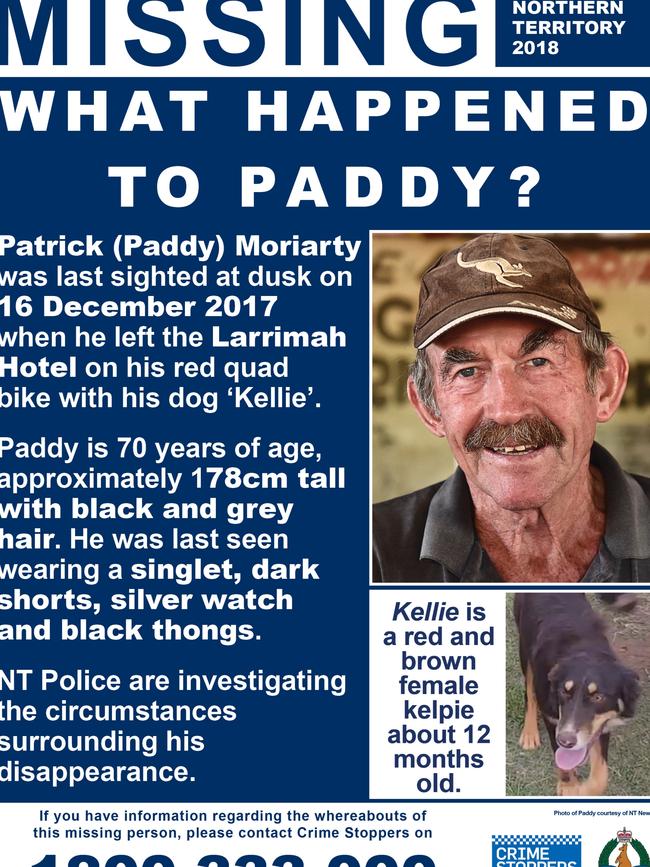

The bare facts of the case have been told again and again: on December 16 last year, Moriarty hopped on his quad bike with his puppy, Kellie, after an afternoon sipping beer and headed down a dirt track to his home at the other end of town.

A tourist family who Moriarty had spent the afternoon chatting with gifted Moriarty a leftover roast chook for Kellie, and Moriarty said his goodbyes.

Neither Moriarty nor Kellie were ever seen again and an ongoing police investigation remains largely focussed on the theory that Moriarty met with foul play.

■ ■ ■

LARRIMAH is a town in limbo.

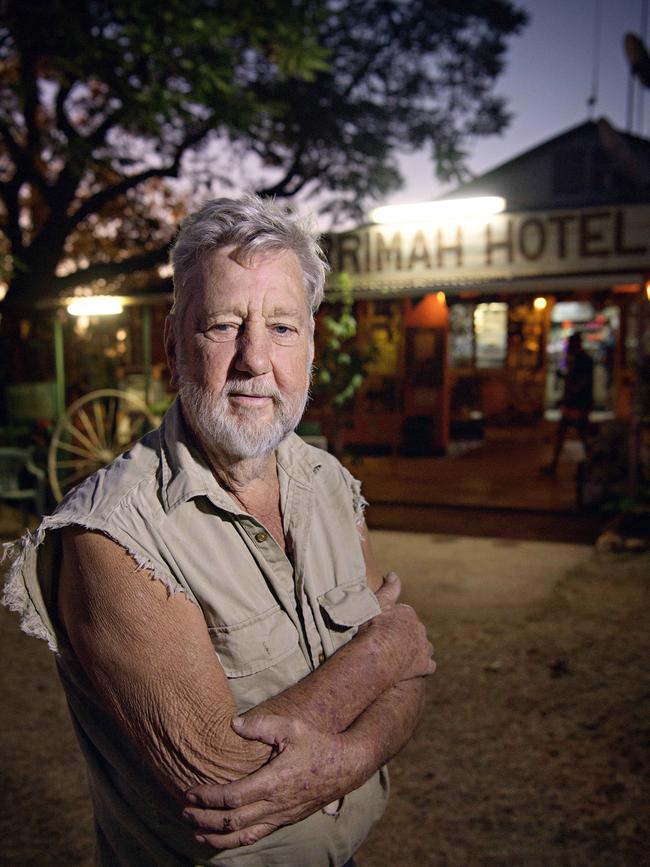

“I don’t think there’s much hope for poor Larrimah,” says recently retired publican Barry Sharpe.

“The government is not really interested in it.

“A little town like this, you’d think the government would be pushing it to go ahead, but no.”

Mr Sharpe is the closest Larrimah has had to a mayor in recent years; the pub he owned until he sold up recently — the Pink Panther — was the beating heart of the town.

It was where Moriarty worked most mornings and drank most afternoons.

Now, it is where tourists come to gawk and take photos of the empty barstool in “Paddy’s Corner”, or of the missing person poster police put up out the front of his house at the northern end of town.

To visitors, Moriarty’s disappearance is just another curiosity along the tourist trail; to his friends, it is the source of a deep and unresolved grief.

“To them its something exciting that’s happened,” Mr Sharpe says.

“But I myself miss Paddy because he was such a good friend to me and I don’t really understand why it happened, I don’t.”

“We know he’s gone, we talk about it, it’s all part of the common day’s conversation in a way. People come here, ask questions, all types of questions, you just answer the questions.”

Moriarty, too, is in a kind of limbo — he is gone, and formally “missing”, but can’t be declared dead.

Mr Sharpe, like most people in town and the thousands of outsiders who have taken an interest in the case, has a strong theory about what happened to Moriarty.

“I believe I know what happened,” he says.

“I know all the people in town and, well, there wouldn’t be very many of them who would be capable of killing someone, or even have the will to do it.”

Mr Sharpe’s theory is one he has repeated time and again to police, reporters from around the world, and the daily passers-by.

“If they keep going, I believe they will crack it,” he says.

“But it’s very frustrating, very frustrating, because there’s not a thing you can do.

“You can’t go over there … and say ‘you’re a murderer and you did this and you did that’, you’ve just got to carry on with life.”

■ ■ ■

UNTIL June, Larrimah had another mystery.

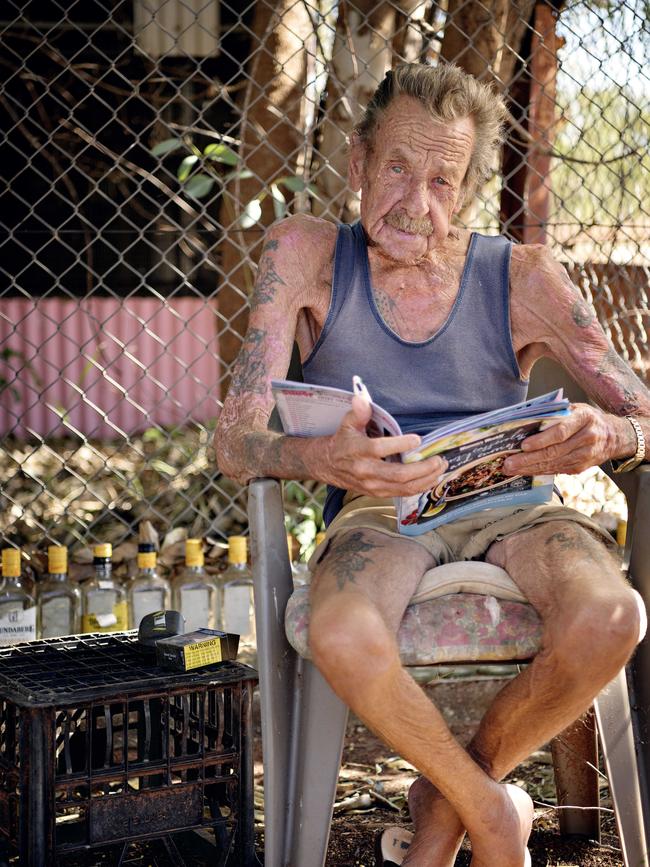

A man had moved in with Moriarty’s sworn enemy, the town’s pie cook, Fran Hodgetts.

Ms Hodgetts had for months been advertising in the newspaper classifieds for a live-in gardener, who would work for board and keep.

Eventually, she received a reply from a reclusive and crippled old tent boxer and railwayman, Owen Laurie, who had been living in a caravan by a well on a cattle station near Katherine.

When he moved in, Larrimah’s population swelled to 12, but until June, nobody in town other than Moriarty had seen Mr Laurie up close.

It wasn’t until Mr Laurie was filmed and photographed leaving the coronial inquest into Moriarty’s death at Katherine Courthouse in June that Mr Sharpe saw what he looked like.

“I just saw a bloke wandering around Fran’s place every now and then,” Mr Sharpe said.

“Paddy told me that Fran had a gardener living with her, but he didn’t come and say hello, and we didn’t know what he looked like.”

The inquest heard Moriarty had seen Mr Laurie up close, when the two had a tense standoff about Kellie‘s barking and Mr Laurie said, “shut your f**king dog up or I’ll shut it up for you”.

The coronial focused most closely on Mr Laurie and the now-infamous Ms Hodgetts.

She has repeatedly and vehemently denied any involvement in Moriarty’s disappearance, as has Mr Laurie.

She told the inquest she was out of town when Moriarty was last seen and said she “couldn’t do it anyway” because she was “riddled with arthritis”.

Words come out of Ms Hodgett’s mouth like bullets come out of a Gatling gun, although she would not speak to the NT News in the days after the inquest, saying “me barrister” Tamzin Lee had told her “no more going on the telly, no more interviews”.

Mr Laurie, who the inquest heard was “hot tempered”, is a powerfully built man but similarly crippled.

The inquest, in a packed conference room in Katherine courthouse, heard that in the days before Moriarty disappeared Mr Laurie had “joked” about killing him.

He agreed he said, “if any f**king bastard comes in here and poisons my f**king garden, that’ll be the first murder in Larrimah”.

“That was joking. It was said jokingly. People say things like that,” he said.

“I had no intention of murdering anyone.”

He said Ms Hodgetts was embellishing the truth in her statement to police that, before she left town for a few days, she had told Mr Laurie, “don’t do anything stupid, I’m going to Darwin I don’t want to come back and have to bail you out of jail”.

Those revelations — first made public at the inquest — left the other residents aghast in the days afterwards, as they passed around the Pink Panther a copy of the NT News that someone had driven an hour to Mataranka to buy.

■ ■ ■

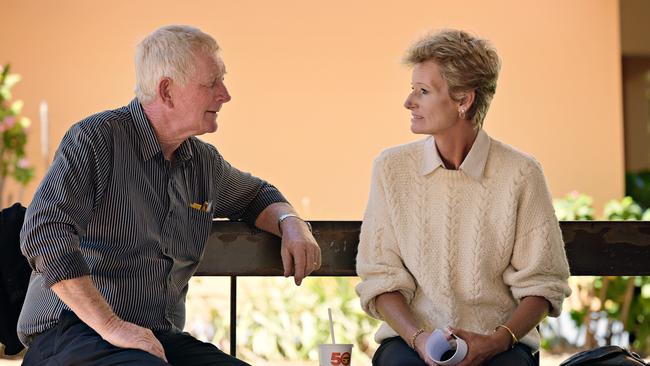

THE town’s newest arrivals, Mark and Karen Rayner, ended up in Larrimah almost by happenstance when they were travelling around the country.

“When we sold up and hit the road we had really no idea we’d be part of this, you know, our very own murder mystery or whatever,” Mr Rayner said.

Ms Rayner said it was on the park benches in front of the courthouse during the inquest where residents “sat down and talked for the first time in a long time”, putting many of their petty gripes behind them.

While all small towns thrive on gossip and dispute, the rift between Moriarty and Ms Hodgetts seemed a “Hatfield and McCoy” style schism.

While Ms Rayner says Larrimah has become quieter and more friendly “since Paddy left”, she hopes that whoever was responsible for his disappearance — and likely death — faces justice.

“You just know he’s not there. His chair’s still empty,” Ms Rayner says.

“To us, there was a big hole when Paddy left, because he was bright and cheery … and the only person who ever in Australia calls people ‘folks’.”

“We hope for Paddy’s sake that somebody is made to face the consequences of their actions, regardless of what happened.”

Moriarty wasn’t alone in despising Ms Hodgetts.

Out the front of the pub, Ms Hodgett’s ex-husband, Billy Hodgetts lives in a caravan, which he deliberately parked up against the fence line so Ms Hodgetts would see it every morning.

“I did it to piss her off,” he says.

Mr Hodgetts, a retired truck driver who speaks with a drawl after having his tongue and part of his jaw surgically removed, says he “wouldn’t mind living in Mataranka” up the road, but won’t leave until his ex does.

“I came down on me own but she said ‘oh I don’t want to, f*cking Jesus you’re not going to get me living down there’.

“Now I can’t get her out with a team of buffalo.”

Mr Hodgetts says he wants to know what happened to Moriarty.

“I can’t see it (happening),” he said.

“I hope it does, you know, we just want to get some clarity.”

■ ■ ■

NOBODY who lives in Larrimah is from Larrimah.

They have all found themselves there for one reason or another and Moriarty had come further than anyone else.

Born in Limerick, Ireland, to a single mother, Moriarty was 18 when he took part in the great Irish tradition of leaving Ireland for a better life.

He traded the dreary shores of his home country for the blistering heat of the outback.

Moriarty was a tough man — winning the steer wresting buckle at the Darwin rodeo in 1996 — and he was generally friendly, although if he had a few more beers than his usual fill his Irish temper could come out.

At least part of what Moriarty must have liked about Larrimah was the relative solitude. He sold up his old house in Daly Waters in 2006 to buy the old Top o’the Town roadhouse, the disused service station where he lived until he disappeared.

In Larrimah, Moriarty seemed to have all he needed for a charmed life: a few good mates, a pub, a dog, enough pension money to get by and a bit of work for beer money.

Moriarty had planned to stay in Larrimah for Christmas.

When Moriarty hadn’t been seen for two days, Mr Sharpe swung by and knocked on the door.

The next day Mr and Ms Rayner went over and pushed open the unlocked back door.

Ms Rayner would later say the house, undisturbed, had an eerie feeling about it, as if frozen in time.

There were no signs of a struggle, or of forced entry, and Moriarty’s three-day old dinner sat ready to be reheated.

The day he disappeared had been crossed off Moriarty’s calendar and there was no sign of him on the road towards the tip.

Perhaps most telling was his signature beige cowboy hat was left behind, an oddity considering he would never leave the house without it, to the point that one of his oldest mates, Phil Garlick didn’t know Moriarty was bald.

Mr Garlick, who sat through the entire inquest and who visited Larrimah most years until Moriarty went missing, was typical of the larrikins Moriarty surrounded himself with.

He was apologetic he had little to share with the NT News about his mate, and that he didn’t have any stories to tell better than the last time he called the paper.

“You did a story about a chicken I had with three legs and two arseholes,” he said.

“Paddy was just a very good mate.”

■ ■ ■

NT POLICE would launch what became of the most in-depth searches ever conducted in the Territory.

Detective Sergeant Matt Allen, the major crime investigator in charge of the Moriarty investigation would tell the inquest it was “unlikely” Moriarty was above ground in the area around Larrimah.

“I’m confident with the search efforts that if he was above ground within the area that we’ve searched that we would be able to locate him, or a sign of him and his dog,” he said.

“Essentially every resident of Larrimah has given multiple statements

“They were spoken to by Katherine detectives initially, then we’ve come and asked for further detail.

“The questions keep getting asked as the investigation progresses. All residents of Larrimah have provided statements, and quite often numerous statements.”

Sgt Allen agreed not all residents of Larrimah were “particularly pleased about the attention and having to provide statements”.

In the scrub around town, the remnants of the police search remain — faded pieces of pink tape dangling from tree branches, showing the ground search teams had covered, walking shoulder to shoulder

Sergeant Meacham King, a search and rescue specialist, said by the time the second search for Moriarty began just after Christmas, police were looking for a body.

“Nothing turned up of any interest,” he said.

Police searched along roadsides and tracks for 50km around town, by helicopter and shoulder-to-shoulder in the scrub immediately around town.

“I’m pretty confident that if he was walking around … we would have found him. We can see (from helicopters) small 20 litre drums.”

He said the way Moriarty’s house was left “just didn’t sit right with me”.

“In all the jobs I’ve done, I just, I think there’s something else to this.”

He said if Moriarty had been buried in a shallow grave, there was a “possibility you could just walk right over him”.

Mr Rayner, who spent the afternoon looking for Moriarty before police showed up, said any criticism of police not magically “solving” Moriarty’s disappearance was unfounded.

“Given what they’ve been up against I think they’ve done a pretty good job,” he said.

■ ■ ■

MCMILLAN named his essay on the town after an observation resident Karl Roth made to him: “we’re all eccentrics in a town like this”.

McMillan’s 2006 essay was from a time when the town had a comparatively metropolitan population of 20.

Mr Roth lives with his wife, Bobbie, across the road from the pub in the old post office, surrounded by a lush garden.

The two moved to town to be with family when both of their daughters lived in town, one of whom, Di Rogers, owned the Pink Panther.

For many years, they had everything they wanted — Larrimah was a quiet place to while away in semi-retirement while earning a steady government income being on call to show up to road accidents on the Stuart Hwy.

One day, many years ago, a wealthy Alice Springs businessman rolled his car on the highway, trapping himself inside.

When Mr and Ms Roth got to the car in the fading light, Mr Roth instinctively whacked and killed what he thought was a rodent sniffing around the wreckage.

“It was his toupe,” Ms Roth says.

To Ms Roth, Moriarty was a “nasty old man”.

“Everyone’s saying what a gentleman he was, but if he saw me … he would hurl abuse and swear … so I just avoided him,” she said.

Mr Roth says the sooner police find out what happened to Moriarty the better “so we can get back to a normal life”.

Mr and Ms Roth are sick of the “comings and goings” of police, the world press, as well as what Mr Roth describes as other people in town “pointing fingers at each other”.

“It is sad to see Larrimah become associated with this case.”

Ms Roth says the documentaries and news reports have unfairly painted Larrimah as being a town of “hillbillies”.

“One of them even had banjo music, I had to turn it off,” she said.

“How can we be hillbillies, if there aren’t even any hills?”

■ ■ ■

WHAT lies ahead for Larrimah is a vexed question.

Mr Sharpe and Ms Hodgetts are both seriously unwell, and the investigation into Moriarty’s disappearance — like many homicide investigations — has slowed, although police are confident that if anyone did kill Moriarty they would be unable to keep their secret forever.

Earlier this year, the Pink Panther was sold to Tennant Creek businessman Steve Baldwin, marking the end of an era for the town.

The Rayners are reportedly thinking of moving on.

If one thing does seem certain, it is that Moriarty’s disappearance will forever be tied up with Larrimah — a story which turned a town in the middle of nowhere into the “centre of everything”.

As much was obvious when Coroner Greg Cavanagh queried why so many reporters and onlookers were crammed into his conference room at the start of his inquest.

Never one to miss a beat, Mr Cavanagh’s offsider, Counsel Assisting the Coroner Kelvin Currie, said: “Your Honour, I think they’re going to write their book on it, a bit like Wolf Creek, in due course.”

“Yes, I suppose,” Mr Cavanagh said.

Wolf Creek, a semifictional mishmash of Ivan Milat and Bradley Murdoch, deals with a kind of devil we know.

The story of Moriarty’s disappearance is scary in a different way.

It is the story of a strange man and his dog, in a strange town, who vanished without a trace into the vast outback.