London calling for Aussie conmen of early 1900s as Squizzy Taylor makes (crime)waves back home

As gangland figure Squizzy Taylor made (crime)waves in Melbourne, a host of Aussie conmen preferred to swindle and rob gullible Englishmen — and what better way than at the races.

Book extract

Don't miss out on the headlines from Book extract. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For over 170 years Australia has exported some of its ï¬nest criminals to America and Europe where with tales of sudden inheritances, lucky rosaries, sleight of hand and particularly infallible betting systems, unbeatable horses and sheer brazen cunning, they have swindled and robbed the gullible natives.

By the late 1890s they were firmly established in London where the Australian gang was known as the Hanley Mob. Luminaries such as Matthew Biggar, Danny Melaney, Alf ‘Double Ace’ Lawson and later James Mann, known as James Coates, continued their predations until after the Second World War, when Scotland Yard thought they had more or less all died, retired or gone home.

Highly regarded as one of the great ‘tale-tellers’ among his peers, Melaney’s sidelines included acting as a go-between with receivers and as a procurer of false passports. Born in 1870 and with a kiss curl of straw-coloured hair, bulbous pockmarked nose and a waddling gait, it was said no one looked less like a conman than he did.

In 1908, along with two other Australians, he planned not only to steal the Ascot Gold Cup but also two others on display at the meeting. He was thwarted when absolutely out of the blue another man walked up to the unguarded Cup, took it off its pedestal, and walked away with it.

The next year Melaney was sentenced to five years for distributing the proceeds of a spectacular jewel theft at the Cafe Monaco in London’s Regent Street, then a home away from home for Australian confidence men and where they had given a dinner for the visiting Western Australian detective Chief Inspector Harry Mann.

Organised by the great East London receiver and putter-up Joseph ‘Cammi’ Grizzard, the French jeweller Frederick Goldschmidt was followed from Paris in June 1909 by at least two teams and when he finally put down his bag containing something in the region of £60,000 worth of jewellery in the washroom of the Monaco and reached for the soap, it was snatched by the ex-jockey Harry Grimshaw.

A story is that when the police searched Grizzard’s home that evening he hid a diamond necklace from the haul, which he had yet to fence, in a bowl of pea soup. Other accounts have it that the necklace was hidden in Mrs Grizzard’s underwear before she went to the outside dunny, somewhere the delicate-minded police of the day would not search.

In March 1910 Melaney was threatened with extradition to Austria over the theft of 1000 notes at the main Vienna Post Office in July the previous year. He had clearly been moving around because he told the court, ‘I have already been tried for that in New York’. Two months later he was discharged when the necessary depositions had not arrived from Austria.

Other long sentences followed and Melaney received four years at the Old Bailey in November 1923 over a card swindle known as Anzac Poker. Towards the end of his career, in 1933 he was acquitted of a more or less selfless conspiracy to smuggle tobacco into Bedford prison. In London the next year, then aged sixty-four, he received eighteen months for obtaining £231 by a trick. He had left coal dust instead of banknotes in a wallet. By then he had nineteen previous charges going back to 1904 and had been deported from Belgium, France and Austria. A broken man, he died in a Marylebone hospital in London in 1938. He had been suffering from cancer. The English criminal Val Davis thought well of him:

In fifty years of profligate living he had committed no hurt on a defenceless person, or robbed those who could ill-afford the loss. He was a friend to all beggars and impecunious crooks. To him ‘honour among thieves’ was a ritual — faithfully observed in his half century of ill-doing.

Indeed Davis thought highly of Australian confidence men generally, writing:

Only among Australian conmen is there any definite degree of comradeship. I have seen these ‘boys’ ask for loans from a fiver to a grand (£1000) and the money has been passed over without the bat of an eyelid. If one of the ‘mob’ falls he will be looked after from the moment the cops pull him in.

In the pre-First World War years others followed Melaney, one of the most successful being William Charles Warren, born in 1868 and known as ‘Bludger Bill’ or ‘Bill the Bludger’. In his own reminiscences of confidence men in London, the detective Charles Leach thought Warren, whom he called ‘The Dodger’, was ‘a rough uneducated Colonial who could barely write his own name’. Davis agreed with him, describing Warren, whom he called ‘Willie Secundus’, as follows:

His voice was raucous, his language loud and often coloured, he dropped his aitches and picked them up in the wrong places. The boys would tell him it was his face that frightened the money out of the mugs. Overall he fitted the impression to be given by an Australian confidence man from the bush who had made his money — rough and ill-educated. The mugs would have been put off if he had been monocled and manicured.

In an early court appearance on 12 February 1901 Warren was sentenced to eighteen months with hard labour at Sydney Quarter Sessions before travelling to Europe where he worked a variety of confidence tricks, including taking money to bet on horse racing. He would promptly disappear with the cash and, when found, would either say quite correctly the horse had lost or, if it had won, plead a defence under the Gaming Acts that made gambling debts irrecoverable at law.

In 1912, posing as Mr Fairle, owner of the Ascot Gold Cup winner Aleppo, he cleared £12,000 from his dupes. The end of this particular trick came nine years later when Archibald Wall, a businessman with interests in Portugal, sued him to recover his lost stake. Wall had met Warren in May 1920 when Warren arrived at the Bushey Hall Hotel near London with a ‘beautifully dressed lady’.

They met again the following week and Warren introduced Wall, who claimed to know nothing about racing, to his infallible betting scheme — taking a horse at a long price in the ante-post market for a big race and betting on it, forcing down the price so covering themselves. As a gesture Warren gave a tip to Wall to bet on the horse Wine and Women and Wall was pleased to find it had won. It was only later, he told the court, he discovered it had been 5–2 on in a twohorse race.

Amazingly Wall was persuaded to invest £5000 on Bruce Lodge in early betting on the Derby and a further £10,000 on Happy Man in the ante-post market for the Newbury Spring Cup. This was a serious mistake because there was no ante-post market for the Cup. Both horses were scratched. Promises to pay were never kept and Warren went to Paris to bet on the Grand Criterium. By the time he returned Wall, who had now done some homework, had discovered Warren’s flat was in his wife’s name and he was about to do a runner.

He sued not for the betting losses, which in law would have been irrecoverable, but brought a civil action for fraud. The jury retired only for a few minutes before awarding him his money. A substantial number of other actions were waiting on the result of Wall’s case and for Warren it was time to think of sunnier climes. When his Australian friends were arrested Warren prudently went to Brussels and then France, setting up home on the Riviera.

In 1920 Alfred Dean, born in Ballarat in 1880 and also known as Alf ‘Double Ace’ Lawson, received five years at the Old Bailey after being found guilty of conspiracy to cheat at cards, specifically the engagingly named Anzac Poker, also known as Kangaroo or Double Ace. The game as played by them was an outright rort. The players — all in the know except the mug — put an agreed sum in the pot and the dealer turned a card. He then bet the whole or part of the pool that the next card would be of higher value than the one he exposed — aces counted low. If he won he took the pool money.

The cards then passed to the player on his left who then bet in the same way. Once there was sufficient in the pool and the third ace had been turned up, the mug was then encouraged to play for the pool since only the fourth ace could deny him. While he was distracted by the players the cards were switched for a second pack. An ace was dealt, he tied and so lost, and a few hands later the pot would be won by one of the other players. An extremely fast-moving game, a pot could reach £12,000 within minutes.

After Dean and his offsiders were convicted the court was told of the amazing amount of money the team had made in the previous two years. James ‘Slab’ Brennan had earned himself £35,482, Maudsley Dudley £47,202 and Dean £57,623. Gilbert Marsh had banked a staggering £60,750 while Charles Mansfield had picked up a mere £4700. To give some idea of their profits, that year a farm with 350 acres (141 hectares) near London could be bought for £23,000; a ten-bedroom house near fashionable Hyde Park went for £5000 and in Gloucestershire in the West Country, a ‘Gent’s Res’ with 220 acres (89 hectares) was priced at £6000.

MORE BOOK EXTRACTS:

Murder, Misadventure and Miserable Ends

While Dean was in Parkhurst prison he suffered a stroke that left him partially paralysed. He turned it to good advantage, however, telling his marks that he had suffered the injury while out riding when his horse stumbled over a wombat’s hole. On his release Dean returned for a short time to Australia but it was then back to England, where he claimed to have worked as a bookmaker in Southampton from 1932 to 1936. Two years later in April 1938 he appeared in court over a betting rort.

Posing as a bloodstock agent who had a farm at Andover, Dean had interested two upright and elderly gentlemen who were only named as Mr A and Mr B in his infallible — for him — betting system. Between them the pair lost £8000 in one afternoon after the system proved fragile at Wolverhampton races. Curiously neither of the men had been to a racetrack before in their lives and it must be supposed they did not do so again.

In court Dean blamed his bookmaking losses for his return to crime. This time he received five years. In May 1931 in Glasgow, as ‘Edward Cavendish’, he was convicted with the British conman Charles Robinson, also known as Montague Newton. The pair were working the age-old ‘Safe Investment’ trick in which a horse is bet on at long odds and then hedged when its price comes down.

This time the mug was Glasgow businessman Andrew Frame, whom they had met at an English spa town, and the horse was The Recorder in the Cambridgeshire, the big autumn mile handicap run at Newmarket. Sadly for Frame, when he went to claim his winnings Robinson told him he had believed the horse was unbeatable and had not hedged the bet. It came third but Robinson said he had placed it all on the nose. And no, he was not as wealthy as he had made out. In fact he was bankrupt and there was no way of refunding Frame his losses. Frame had the courage to go to the police and the pair received three years’ penal servitude apiece.

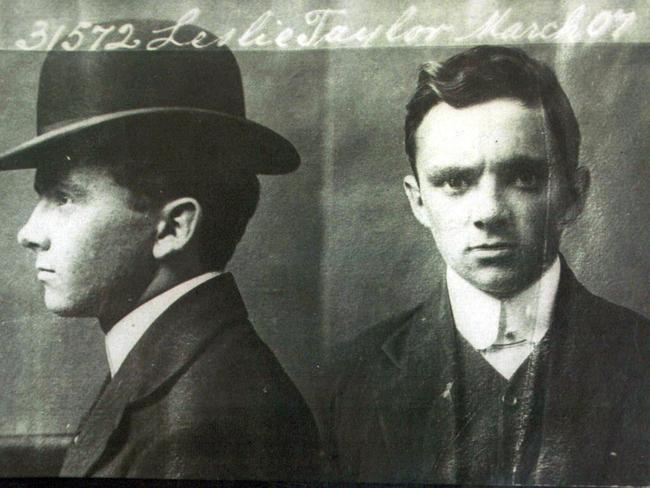

One man who stayed at home was Australia’s so-called favourite larrikin, Leslie Joseph ‘Squizzy’ Taylor. One-time pony jockey Taylor was heavily mixed up with racing. Small enough to be apprenticed as a jockey to the trainer Bobby Lewis, he rode at the Richmond racetrack but his opportunities dried up, as he was considered too crooked even for those days and that sport. His defenders say, more charitably, that he had had weight troubles even though at the time of his death he was still under nine stone (57 kilograms).

He had been a member of the city’s leading Push, the Bourke Street Rats, where he had learned the art of pickpocketing, something which he put to good use at racecourses. In January 1908 he received two years’ imprisonment for pickpocketing at Burrumbeet racecourse near Ballarat.

Sentencing him, the judge, Sir Joseph Hood, remarked that he was now a confirmed criminal.

He was suspected of being involved in both the 1913 murder of Arthur Trotter and the 1915 Trades Hall shooting but was never charged. However, on 29 February 1916 Taylor and another of his gang, John Williamson, hired a taxi driver, William Patrick Harries, for a drive in the country on which they took false number plates, suitcases and glasses as a disguise. The intention was to rob an employee of a bank that had a branch in Bulleen. It seems that Harries would not go along with their plan and, for his lack of co-operation, was shot. At about 11.45 that morning his body was found inside his cab covered with a blanket. Nearby was a partly dug grave and, at a waterhole, were false moustaches, dungarees, spirit gum and glasses. There were good descriptions by three witnesses who had seen the pair with Harries.

Within days he and Williamson were arrested at Flemington racecourse on holding charges of ‘being without means’. Now the witnesses came forward to make positive identifications and it was a short step to a charge of murder.

At the trial in April, the three witnesses were in retreat and failed to make the necessary identification. Taylor had managed to get at them and he also produced an alibi.

Immediately after his acquittal both he and Williamson were charged with perjury. Taylor had said he had worked for the trainer Bobby Lewis and Williamson had said that Lewis recommended him to go to Tasmania to back horses. It appears Taylor may have worked for Lewis. A Lewis brother had sacked a boy named Taylor. The charges were quickly dropped.

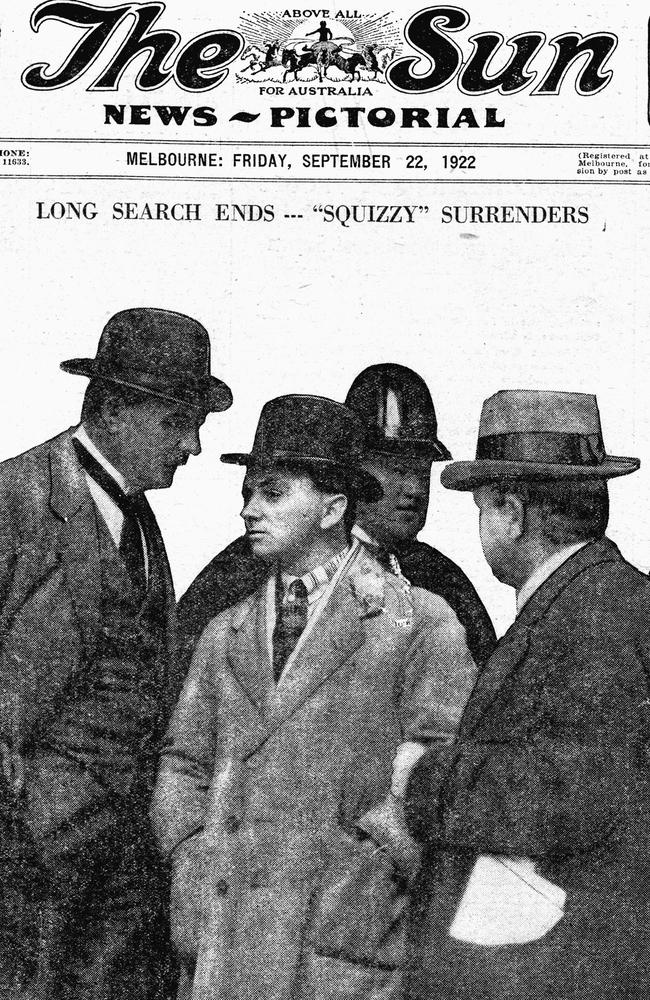

Taylor was, however, temporarily inconvenienced when he was found guilty on the vagrancy charge and sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment. When Taylor was on the run in 1921, hooting, and throwing stones, a crowd of youths swarmed over the fence at the Richmond ground and assailed the umpire in the football match between Richmond and Carlton. Two mounted policemen scattered the crowd, and escorted the umpire from the field. As he was entering the dressing room a section of the crowd again attempted to get at him, and the mounted police had to charge. There was a good deal of stone throwing, but the police did not make any arrests. The crowd kept on yelling at the troopers and constables on duty, ‘Why don’t you catch Squizzy Taylor?’

While on bail in 1922, after being found in a bonded fur warehouse, he attended a race meeting at Caulfield and was promptly warned off. In another example of his spite and bravado, at 4am on 21 October, the night before the prestigious Caulfield Cup, he torched the Members Stand, causing £9000 worth of damage. Despite rewards totalling £1000 and the offer of a free pardon to any accomplice who shelved him, no charges were brought against anyone.

One story is that in July 1924 Taylor was paid to nobble the heavily backed Rahda due to run in the Grand National hurdle race at Flemington. The idea was that Rahda should be given a carrot laced with strychnine so that Bendoc could win. However, the night of the doping Taylor was arrested and held on suspicion of robbery. By the time he was released and reached the racecourse an alarm clock in a nearby stable went off and he and his offsiders fled. In the race itself the top-weight Jackstaff won easily from Rahda, with Bendoc unplaced.

Taylor was an easy scapegoat. When Bob Pratt was hit by a truck on the eve of the 1935 Grand Final and South Melbourne lost to the Magpies, he suggested Squizzy Taylor might have been behind it.

This was difficult to substantiate because the Squiz had been dead seven years.

His final appearance on a racecourse was on 26 October 1927 back at Richmond pony track, where he had a blue with John ‘Snowy’ Cutmore after that man had smashed up a brothel in Tennyson Street, St Kilda, which was under the temporary protection of Taylor. During the rampage Cutmore pulled a young girl out of bed, stripping her naked before turning her onto the street. It was not something that Taylor, even in decline, could allow to go unpunished. There were high words and in the afternoon Cutmore was warned off the course for life. The next afternoon both men were shot to death at Cutmore’s home in Barkly Street, Carlton, probably by each other but possibly by others who wished to see them both out of the way.

• This is an edited extract from Gangland: This Unsporting Life, by James Morton & Susanna Lobez, published by Melbourne University Press, RRP $29.99

Originally published as London calling for Aussie conmen of early 1900s as Squizzy Taylor makes (crime)waves back home