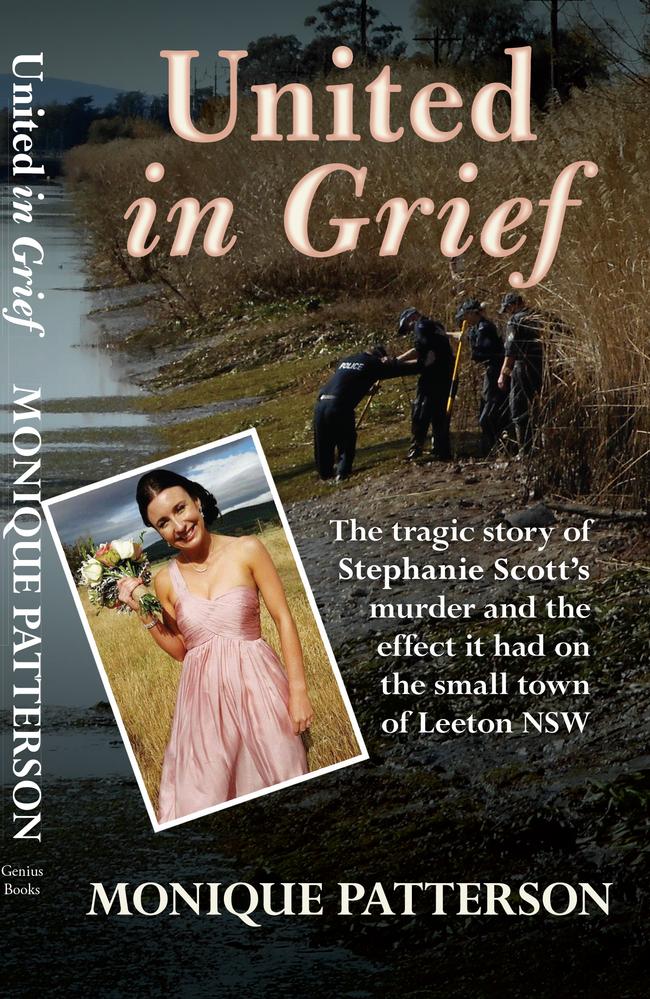

Book extract: A town united in grief over teacher’s horrific murder

Teacher Stephanie Scott was about to marry the man of her dreams. But psychopath Vincent Stanford had been hiding in plain sight, waiting to make his move.

Book extract

Don't miss out on the headlines from Book extract. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The murder of schoolteacher Stephanie Scoptt in the NSW town of Leeton shocked Australia. In this chilling book extract, Monique Patterson looks back on the shocking day that evil broke the heart of the nation on Easter Sunday.

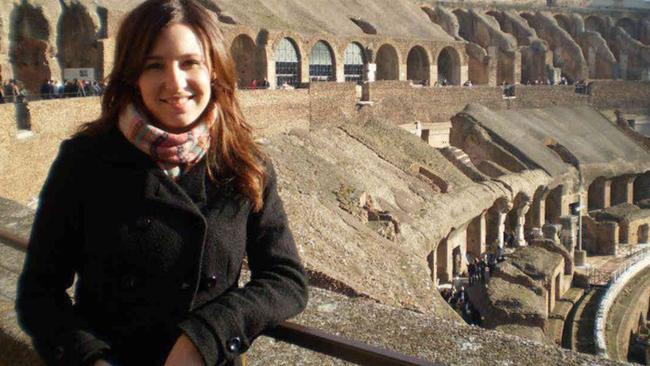

Stephanie Scott had never been happier.

She was about to marry the man of her dreams and celebrate with all her family and friends. She had worked for hours to add personal touches to the special day and when her fiance asked her to head out of town for a party she told him she had a few more things to tick off her to-do list.

One was to head into Leeton High School, where she was a teacher, to finalise plans for the person who would fill in for her at the school in Leeton in the picturesque Riverina region of southern NSW, while she was on her honeymoon.

It was Easter Sunday, 2015.

No one could predict what would happen that fateful day. No one ever thought that evil could break the heart of a town and a nation. But psychopath janitor Vincent Stanford had been hiding in plain sight waiting to make his move.

In the days following the discovery of Stephanie’s body, the change in Leeton was palpable.

In a sense reality had set in. People walking down the street greeted each other in a different way — not with their usual smile and a “morning” or “hey, how you going?” but with a forced half smile and a knowing nod of the head. The line up at the supermarket that once gave residents a few extra minutes to share a conversation with a friend was now a source of great frustration. The town’s set of traffic lights seemed to stay on red longer.

Husbands and wives bickered over minor things they never would have before. Their grief had pushed them to a breaking point. When Stephanie disappeared, residents had a purpose. They had kept themselves busy trying to help locate the bride-to-be. After her body was found, shock set in. Now people were left alone with their thoughts and the dark cloud that had set in over Leeton when it was revealed a monster lived among them.

Stephanie’s family now had the task of planning her funeral. She would be buried at the place she had chosen as her wedding venue — a picturesque function centre in Eugowra. The song that had been chosen to mark the couple’s first dance as husband and wife, Keith Urban’s Making Memories of Us, instead was played as the 26-year-old teacher was buried.

The lyrics were almost too much for Stephanie’s fiance to bear. The two had sung it together many times before; I wanna sleep with your forever, And I wanna die in your arms. That is something that he had pictured — the two growing old together surrounded by children and grandchildren. The grey sky over the function centre was briefly brightened as dozens of yellow balloons were released. But it was a fleeting moment overshadowed by the total injustice of it all.

Once again the Scott family remained stoic — how they were able to do this to ensure their darling daughter had the send-off she deserved remains a mystery.

Stephanie’s sister Robyn said what the whole world was thinking: “The world is far less bright without her in it. Our lives less full and our future less whole. How can this happen to someone so good?” Stephanie’s sister Kim told mourners the beloved teacher had a strong sense of who she was. “Steph never cared what anyone thought of her,” Kim said. “She had an easy way about her that meant she could get along with anyone.”

In Leeton, businesses closed between 1pm and 2pm as a mark of respect. The usual hustle and bustle of the main street was replaced with an eerie quiet. It mirrored the status of the hearts of residents — closed. In another unexpected turn of events and one that people didn’t quite know how to take, Vincent Stanford’s mother Anneke asked Leeton mayor Paul Maytom to pass on her condolences to Stephanie’s family. She said she had been suffering from shock and grief since her son was arrested. Mr Maytom said: “Obviously, she herself is traumatised by this whole incident too. I think it [is] a good thing to let her know we are there for her and give her the opportunity to talk to someone.”

After the service, Stephanie’s nearest and dearest returned to her hometown of Canowindra to continue to celebrate her short life and the unforgettable stamp she left on the world.

In the days, weeks and months that followed the sombre day, their thoughts would turn to ensuring justice was served. Vincent Stanford had changed Leeton, its residents and its story forever. He had taken one of their best. And for that he had to pay.

The public wanted to know about the man who had made them question everything they knew. The media put on their detective hats and began searching for any snippet of information that may provide a clue, a moment in time, an action that may have led him to snap. Or evidence of a psychopath in the making.

Leeton residents were not alone in their fears.

Like many senseless murders before it, Stephanie’s death was a constant in the minds of Australian women everywhere.

Former Leeton resident Michelle Gordon said it was a sad state of affairs. “What happened to Stephanie Scott is an absolute tragedy. It’s sickening, and speaking to women in Leeton I know they are scared. I think self-defence skills are something all women should have.”

Natasha Stott-Depoja, who was once Australia’s Ambassador for Women and Girls, said in an article for The Daily Telegraph, Stephanie’s “murder has made us sad and angry. The notion of women as prey is insidious and unbearable, yet our society has seen many such cases this year alone. The frustration and sorrow with which Australians responded to the death of Stephanie Scott have highlighted the growing momentum for change and for the violence to stop.”

Ms Stott-Depoja said sexual assault, domestic and family violence were the nation’s shame. “Australians are sick of the statistics,” she said. “This is our national emergency.” Jacqueline Lunn wrote an article for website Mamamia about Stephanie’s death. “There is a reason a woman feels fear,” she wrote. “There is a reason fear wins over logic when you are a mother. Men like Stanford are that reason.”

It was not the first time Australians had been shocked and deeply saddened by the senseless murder of a beautiful young woman with her whole life ahead of her. On September 22, 2012, Jill Meagher was out enjoying a drink with friends. After leaving a pub in Brunswick, a suburb of Melbourne in Victoria, the 29-year-old was raped and murdered while walking home. She was killed by a man she didn’t know and CCTV footage from a shop Jillian walked past on the night she disappeared showed she was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. It shows her talking to a man wearing a blue hoodie at around 1.42am. She most likely was simply polite to the man who would ultimately take her life. The man was Adrian Bayley, who is now serving a life sentence for Jill’s murder. Jill had worked at the ABC and, like Stephanie, “she touched the lives of many,” a statement issued by the ABC said.

The lack of emotion Vincent Stanford displayed during each of his police interviews was striking.

He detailed how he ended the life of the schoolteacher — all the while appearing calm with his hands resting in his lap. If he felt even a shred of guilt it was not evident, telling police “I went about my day” after Stephanie was dead. It took some prodding, but he eventually told police that he took Stephanie’s body to Cocoparra National Park after killing her.

One thing that was surprising to police — perhaps because it indicated Vincent may have some sort of remorse for his actions — was that he quickly admitted to killing Stephanie but initially denied raping her.

However, he did ultimately decide to plead guilty to both charges. Vincent told the officers interviewing him that they would find key pieces of evidence at his home in Maiden Avenue. He also told them they would find blood in the room in which she was killed at Leeton High School, despite his best efforts to clean it with a pressure cleaner. He calmly recounted how he drove Stephanie’s body — in her vehicle — to Cocoparra National Park in the early hours of Monday morning, after killing her earlier that day.

“The time I got there might have been 2am in the morning,” Stanford told police. His memory of the day didn’t waver, but when he was asked why he did certain things, he struggled to come up with an answer. “I think I might have some mental problems,” he eventually admitted.

Vincent told police he had dumped Stephanie’s car after taking her body to Cocoparra National Park then walked several kilometres home. Police asked Vincent about the number of scratches on his face. “When did she do that?” “When I tried to … when I killed her,” he replied without emotion.

He told police that when he saw Stephanie working on her computer in the staffroom at Leeton High School on Easter Sunday, something came over him.

When asked by police to describe the feeling, he said: “That I had to kill her. I wasn’t angry or anything. I was emotionless — just that I had to kill her.” Vincent told police that just before he grabbed Stephanie, she said to him: “I’m going, have a happy Easter.” Vincent was extremely candid in his police interviews, but there were some facts the judge ultimately disputed. What Vincent did tell them was, “I went to high school about 7.30, worked for a couple of hours.” He had gone to the school to work because he was bored. “Just wanted to go to work.” he had said. Vincent first saw Stephanie when she was in the staffroom working on her computer. When she was done, she headed for the school exit. She saw Vincent and, in her usual friendly manner, told him: “I’m going now. Have a good Easter.” Just like she had done to each and every person she had encountered in any aspect of her life, she shared a genuine smile and a cheerful greeting. It was just who she was. Stephanie clearly did not feel any imminent danger before she was attacked from behind while attempting to find her keys in her handbag.

How tragic that her trusting nature put her in such a vulnerable position.

“When she was ready to leave about 11.30 I took her into the store [room] and killed her,” Vincent told police. When sharing these details, Vincent appeared smug, almost proud of his actions. He told police he put his right arm over Stephanie’s mouth and his left arm around her middle. She struggled violently as he walked backwards, dragging her along a corridor to a storeroom which had previously been used as a photography darkroom. Stephanie put up a good fight, scratching Vincent’s face and yelling for help, but sadly the sadistic killer was too strong. He told police he had had a lot of violent thoughts in the past but had never acted on them before. He said he had entertained the idea of hurting or killing various people he had met. Vincent was asked why he was angry at Stephanie Scott.

He replied coldly that he wasn’t angry, that he just wanted to kill her.

That was a foreign concept for police and the public who would later learn of this detail. In a second police video, Vincent again sat calmly with his hands on the table. He could have easily been at a bank opening a new account — that was how unaffected he appeared by the whole thing. The fact that he was facing life in prison didn’t seem to weigh on him. The fact that he had destroyed the lives of so many didn’t seem to keep him up at night. In fact, he actually said he enjoyed the solitude that the walls of a jail cell offered. He showed no reluctance to answer the numerous questions asked about the murder. In fact he showed no emotion at all. Vincent was asked where he put Stephanie’s earrings and engagement ring. He told them he didn’t remember. He threw his hands up and said: “I don’t know, chucked so much stuff out.” Police asked whether he got rid of the ring along with Stephanie’s clothes and other belongings. He told police he would have disposed of the ring in a bin somewhere. “But you do remember taking her engagement ring off her finger at the school?” the police officers asked. “Yeah, she wore two rings,” Vincent replied. Police, confused that Vincent would take the time to remove her rings, asked him what had prompted him to do so. “I don’t know, I was just scrambling up her stuff, making sure I didn’t leave anything behind.” Police pressed Vincent on this issue, where the engagement ring was, for some time. “It would be in a bin somewhere, but I have no idea where,” he told them. The reason for this would become clear later on when further details of the day in question were revealed. At times, Vincent seemed to question his own behaviour. When asked why he kept Stephanie’s bra he callously replied: “I honestly don’t know. Maybe I wanted a souvenir.” “Something to remember it by?” the police officer asked him. “Probably, I had no real reason to keep it.”

It is believed taking trophies helps a psychopath prolong the fantasy of the act they committed, although it is unknown whether this is the case with Stanford because he told police he rarely thought about the day he killed Stephanie.

This is an edited extract from United in Grief by Monique Patterson, RRP $21.74, Genius Book Publishing

Originally published as Book extract: A town united in grief over teacher’s horrific murder