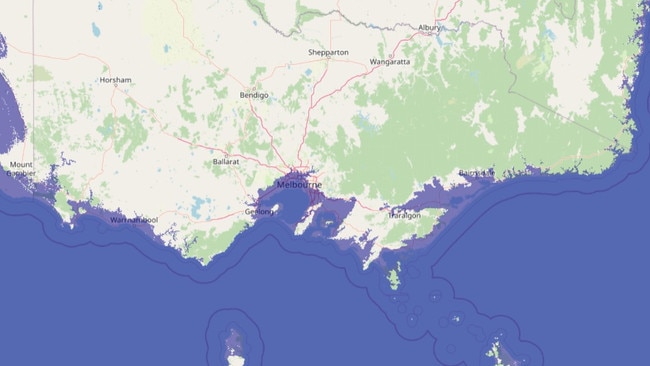

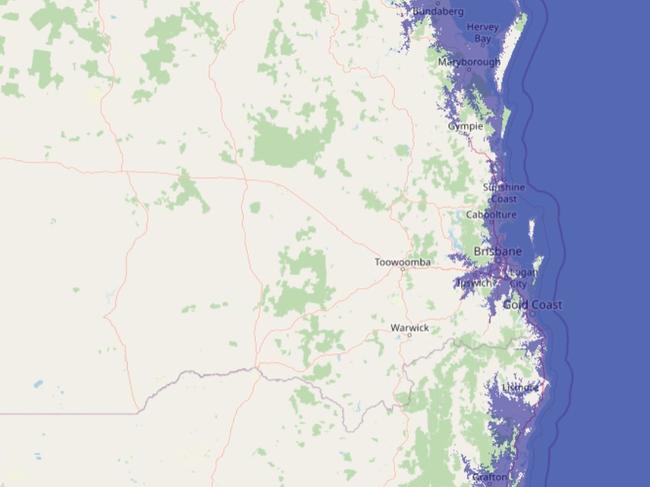

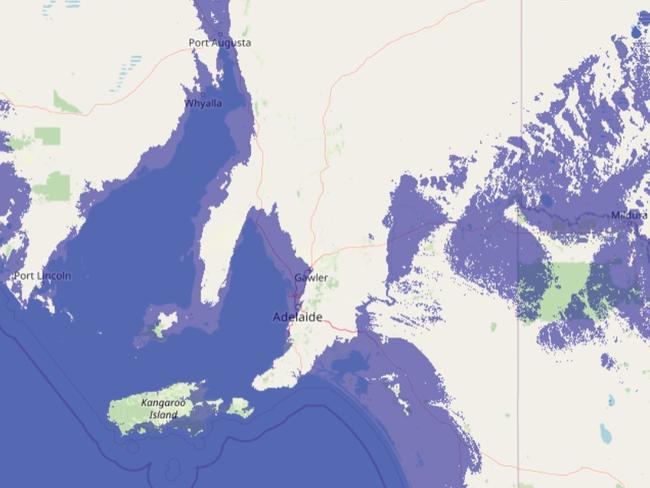

Melting ‘Doomsday’ glacier could leave most of inhabited Australia underwater

Antarctica’s “doomsday glacier” is in trouble. And it could trigger an irrevocable chain reaction adding three metres to a global rise in sea levels.

Climate Change

Don't miss out on the headlines from Climate Change. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Antarctica’s “doomsday glacier” is in trouble. Once it lets go, it will trigger an irrevocable chain reaction adding 3 metres to a global rise in sea levels. And that’s just the start.

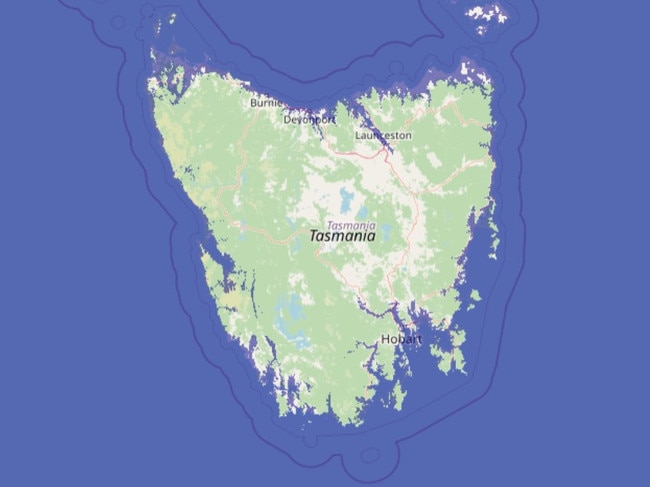

Thwaites Glacier is called the “doomsday glacier” because the collapse of this 192,000 sq/km chunk of ice (three times the size of Tasmania) would bring about a catastrophic rise in sea levels. And that’s without adding any contribution from Greenland or the Himalayas.

Now new surveys are adding evidence to fears the glacier is teetering on the edge.

“Thwaites is really holding on today by its fingernails,” warns British Antarctic Survey marine geophysicist Robert Larter. “We should expect to see big changes over small timescales in the future.”

Warm water is reaching into cracks and crevices more than half a kilometre below its surface. And these are being gouged into new canyons at the extraordinary rate of 43 metres each year.

Researchers from the British Antarctic Survey have just published two sets of findings in the science journal Nature. These come on top of a related series posted last year.

The upshot is the glacier is being eaten away from below. That means the glacier is rapidly getting weaker – and increasingly likely to fracture.

Scientists remain uncertain when this will happen. Guestimates range from anywhere between five and 500 years.

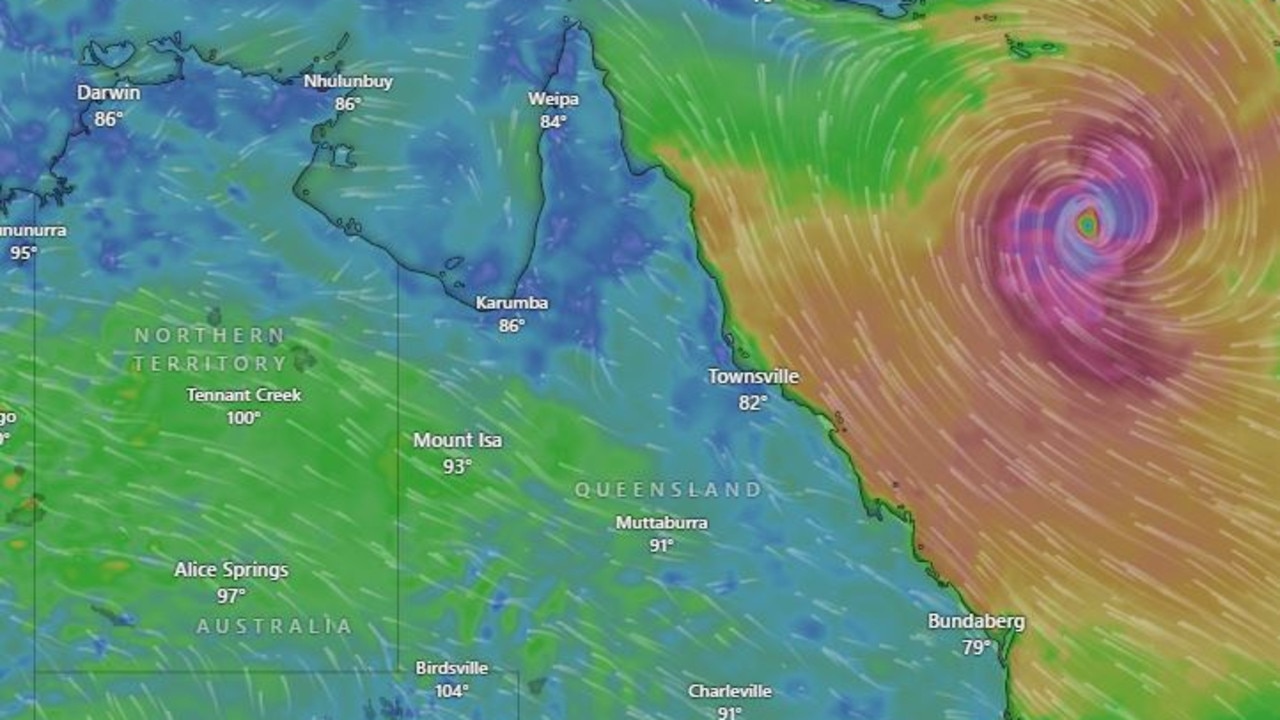

Once it lets go, the researchers say it will trigger sea levels to rise by about 65cm within 100 years.

But that’s just the start of the problem.

Thwaites Glacier is a natural dam to vast lakes of ice behind it. With nothing to stop them, these will slip down continental Antarctica’s gentle slopes and into the sea.

This would produce an additional 3 metre rise.

There is still some uncertainty about the full volume of glaciers and ice caps on Earth but if all of them were to melt global sea level would rise to approximately 70 metres, writes the US Geological Survey. Although there’s no way of knowing when this could happen, it would flood every coastal city on the planet.

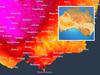

If you consider that Professor Robert Hill from The University of Adelaide has said Adelaide is on track to become a 50 degree city with coastal suburbs such as Grange underwater by the end of the century, this is already an alarming problem for Australia.

Water world

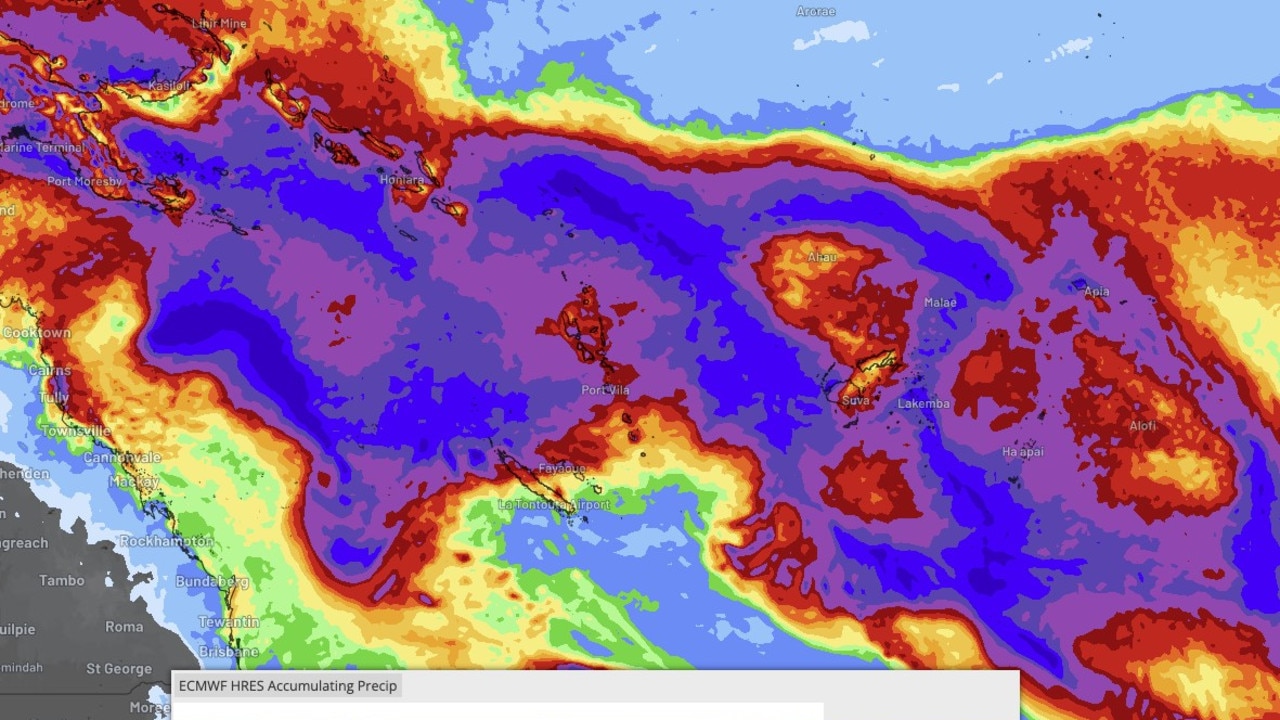

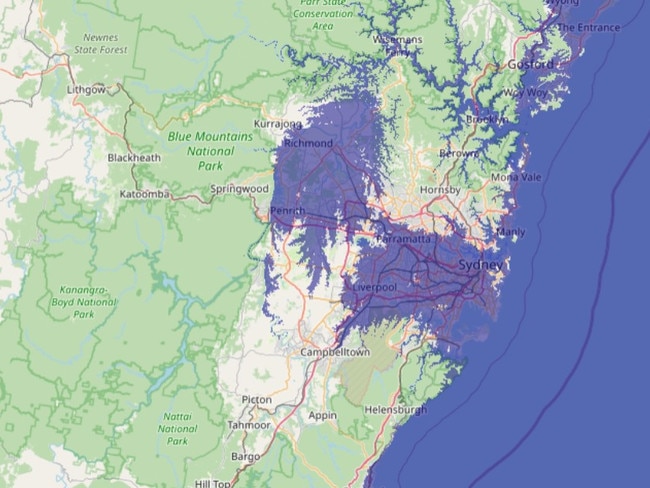

“Considerable development along the NSW coast is at risk from inundation and erosion as a result of sea level rise,” says Climate Central. “Around 80 per cent of the NSW population live within 50 km of the coast. The highest risk occurs close to estuaries, where a lot of development has occurred in low-lying areas.”

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s best-case scenario (immediate, in-depth cut to carbon emissions) projects a 0.5 metre rise in global sea levels by 2100. The worst-case scenario (where carbon output continues to rise) will see an increase of some 2.5 metres.

Many analysts say the world remains on track for the worst-case scenario.

But the 2100 date also creates a false sense of security. If the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets both melt, the US weather service NOAA calculates the resulting sea level rise will total more than 70 metres.

How long this will take to flow over the world’s major cities and prime cropping land remains anyone’s guess.

Click here to see how your area could be impacted

The first sign will be permanent flooding of low-lying areas and increased tidal reach. Sandy beaches will quickly erode, and storm surges will cause increased damage.

“There are a lot of communities that live within what we call the low elevation coastal zone,” University of New South Wales social sciences PhD candidate Anne Maree Kreller told Cosmos Magazine. “We’re talking about a metre – a lot of people live just a metre above sea level.”

But convincing people of the enormity of the threat remains a challenge, she says. “The thing about sea level rise that makes it really difficult to connect to people’s daily life is it’s slow-moving.”

Weak underbelly

The survey team cut a hole through Thwaite Glacier’s 580 metre deep ice sheet. Pumping hot water through a pipe is the quickest and most effective method of doing so.

A torpedo-shaped drone was then lowed into the sea below.

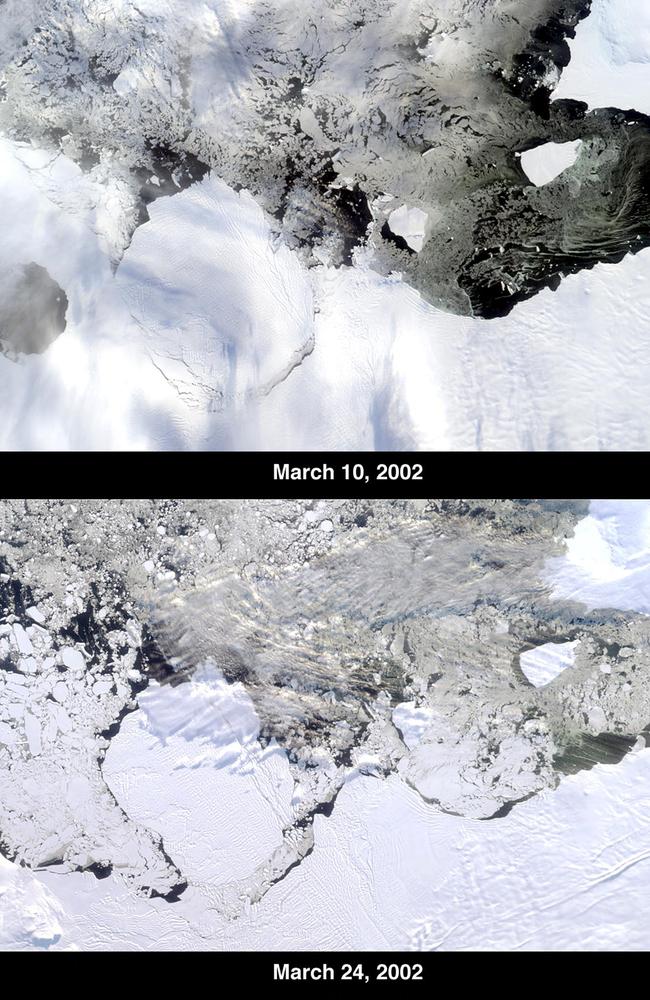

It revealed the underside of the glacier is already being ravaged by climate change. Warm water currents are carving the ice into terraces and crevices. And this helps explain how the 120km wide glacier has retreated some 14 kilometres since the late 1990s.

It has haemorrhaged more than 1000 sq/km since 2000 – about half of all the ice lost from Antarctica.

“These new ways of observing the glacier allow us to understand that it’s not just how much melting is happening, but how and where it is happening that matters in these very warm parts of Antarctica,” says one of the lead authors, Dr Britney Schmidt.

The Icefin drone found an unexpected 2 metre layer of buoyant fresh water coating the underside of the ice shelf. This doesn’t carry as much heat as salt water. And that’s slowing the melt rate to about 5 metres each year.

But averages aren’t the main problem.

It’s about where the worst melt is.

The team of 20 scientists found warm, salty ocean currents have been redirected by shifting wind patterns. These are now blasting through the freshwater barrier to erode Thwaites Glacier at its grounding zone some 500 metres beneath the surface. Here the ice digs into the seabed as a natural anchor slowing the glacier’s advance.

“We see crevasses, and probably terraces, across warming glaciers like Thwaites,” says Dr Schmidt. “Warm water is getting into the cracks, helping wear down the glacier at its weakest points.”

The remote submersible detected salt water currents some 2C above freezing. The research team reported in Nature that the erosion rate these cause is up to 43 metres each year, quickly turning cracks into vast underwater crevasses.

Such rifts will eventually fracture the glacier, accelerating the glacier’s collapse.

Tipping point

When floating ice melts, it doesn’t change sea levels. Like an ice cube in a glass of water, its mass already contributes to the ocean’s depth.

Thwaite Glacier’s ice shelf is like that.

But grounded ice is carried by the bedrock beneath it. So when it melts, it adds to the total volume of water.

Thwaites Glacier is about 1km deep at its grounding point, giving warm currents a lot of surface area to erode.

And here’s where geology kicks in.

Much of West Antarctica’s ice sheet is “bottled up” by a bowl-shaped undersea basin. The lip holding this ice back is about 40km behind Thwaites Glacier’s current ground line.

So far, it remains stable.

But once Thwaites Glacier is gone, the warm currents will relentlessly undermine the grounded ice’s hold on this ridge – causing more to fracture faster and slippages into the sea to speed up even further.

“If an ice shelf and a glacier is in balance, the ice coming off the continent will match the amount of ice being lost through melting and iceberg calving,” says British Antarctic Survey oceanographer Peter Davis. “What we have found is that despite small amounts of melting, there is still rapid glacier retreat, so it seems that it doesn’t take a lot to push the glacier out of balance.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel

Originally published as Melting ‘Doomsday’ glacier could leave most of inhabited Australia underwater