Why NRL decision to axe National Youth Competition will save lives

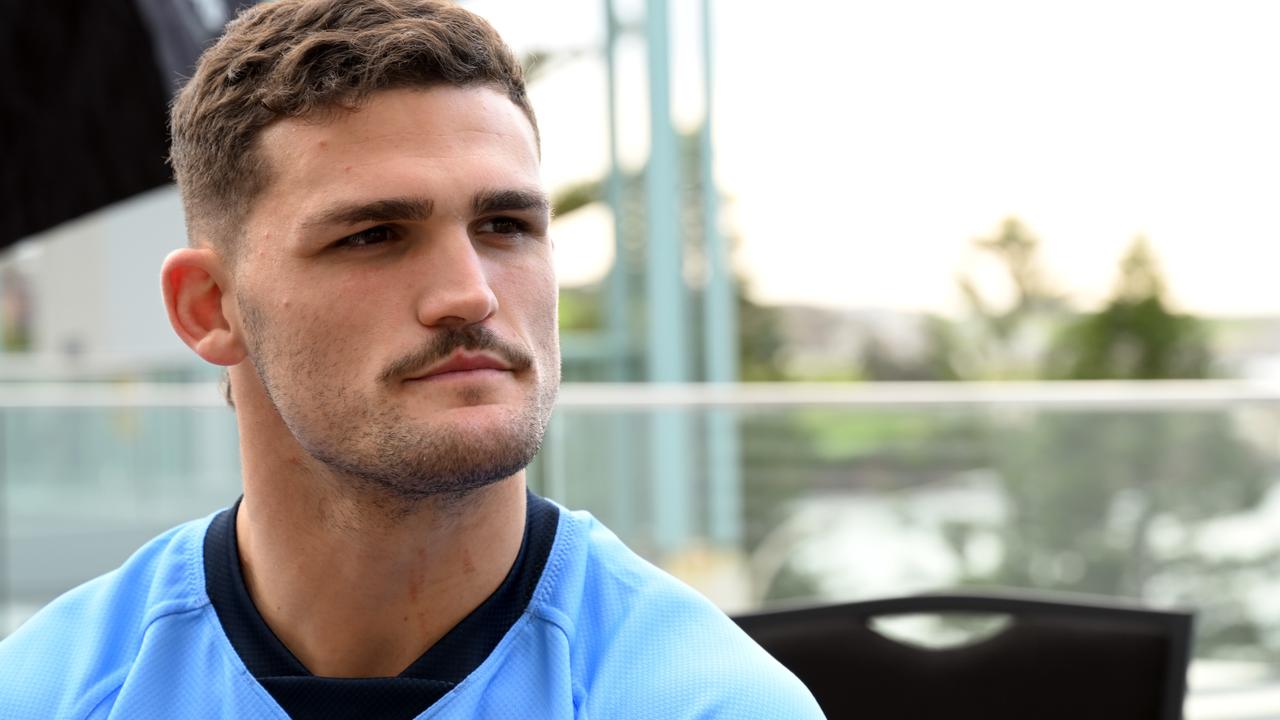

THE son of rugby league royalty, Rhys Jack once waged a brutal mental battle. He hopes the Holden Cup’s demise will help save the lives of young players.

NRL

Don't miss out on the headlines from NRL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

I sat in awe on the sideline, shaking my head and watching the Bulldogs supporters erupt as unknown prodigy Ben Barba zipped through the Parramatta defence like a magician on his way to the try line.

“He’s a freak!” roared Garry Carden, the notoriously old-school Bulldogs trainer responsible for physically preparing the likes of Johnathan Thurston, Josh Jackson and Sonny Bill Williams.

Carden grabbed the kicking tee and water bottles then walked out onto the field to congratulate his man and bark orders at the rest of the team above the ground announcer’s sponsorship messages.

His was a voice you wanted to make sure you heard clearly.

It was round 1, 2008. But this wasn’t the NRL, it was the first ever televised game of the Toyota Cup (now Holden Cup), the NRL’s national under 20s competition, which will be axed at the end of 2017.

NEW HOME: Family first for reluctant Panther Tamou

MOVEMENT: Manly snare talented Titans flyer

UNDEFEATED: Boyd backs golden run to continue

I was sitting on the Bulldogs bench in that game, and — apart from Barba’s memorable footwork and Carden’s voice — can remember only two other things from that particular day.

One was running onto the field in the 72nd minute and scoring an opportunistic try for the Bulldogs. The other was the feeling of anxiety deep in my stomach being unlike anything I had ever experienced knowing my friends and family would be watching on TV.

There was a considerable amount of hype surrounding the launch of the new National Youth Competition that year. For the first time a group of young footballers from each NRL club would be showcased in front of their team’s fans and an international TV audience as they pursued their footballing dreams.

The concept was regarded as ahead of its time and unlike any other pathway for elite sporting talent in the country.

We followed the Bulldogs NRL team around the country, staying in the same hotels, playing at the same stadiums and getting a taste of the professionalism required to one day make the transition into the NRL.

We were also told we had to be working or studying, but for many of us the appeal of playing under the stadium lights was the main focus in our lives.

After a fair initial season, and captaining the Bulldogs NYC team the following year, I tore my rotator cuff in the final game of 2009. The injury required a full shoulder reconstruction and set me up for a difficult period of uncertainty that almost all NYC players would understand.

Around 80 per cent of players never make the transition from the NYC to the NRL, but that statistic often lives somewhere in the very back of a player’s mind when they believe they are close to achieving their childhood dream.

Realistically, the difference between the NRL and NYC is measured astronomically. There’s just no comparing a group of developing 18- to 20-year-olds with seasoned, hardened professionals.

It’s unfair and sets players up for disappointment.

Which is why it’s a positive step for the welfare and development of young players that the NRL will wrap up the NYC at the end of this coming season in favour of placing more emphasis on the open-age reserve grade competitions in NSW and Queensland.

It’s predicted this change will reduce the pressure put on young footballers as they develop and give them a more gradual transition into the pressures of the top grade, rather than dropping them from the heights they experience in the NYC bubble.

It’s a decision which will save lives.

In the months following my shoulder reconstruction at the end of my final NYC season, I was living with severe depression and anxiety, absolutely filthy at myself as a person and putting an unbelievable amount of pressure on myself to succeed as a footballer.

At the time I was playing off the bench in the reserves at the Bulldogs and felt I was travelling through life in reverse.

Investing your every waking moment into a goal only to feel like it is slowly drifting away due to an injury or a form slump or some other circumstance is a horrible feeling.

It’s also a feeling that induces a lot of guilt as you become aware of just how trivial it all seems in the big picture of life.

Since 2013, five young men have taken their lives in the period of transition between the NYC and NRL.

While each of these deaths has its own unique set of circumstances, there are recurring commonalities in the existence of injuries, unrealistic expectations, disappointment, perceived weakness and homesickness all occurring during the pre-season period when a player’s dreams are either brought closer to reality or seem to drift further away.

For many young men determined to make a career for themselves as a professional rugby league player, unrealistic self-expectation and perfectionism can drive them into a vulnerable position.

I’m not saying it’s a cycle that will affect every player, not even close, but it’s something that is out there and those players who do feel it are the ones who need to understand how it can be improved and overcome.

Since I decided to stop playing football in 2012, I completed a second university degree and started a career in construction management.

I also work with the Black Dog Institute to share my experiences with others and bring awareness to the stigma of mental health, particularly for young men.

I made that decision to speak up after hearing about the death of Mosese Fotuaika in 2013. The young prop had a child on the way and the world at his feet but took his own life hours after an injury in the gym.

I remember reading the news of his death and recognising I partially understood some of what he must have felt, that I had been in his shoes. It also dawned on me there would almost certainly be others who felt the same way.

That moment rocked the rugby league community and was a real catalyst which started to open up the conversation around young footballers and their mental health.

From the outside, the NRL seems to have listened to that conversation and continues to take steps in the right direction to improve their health and wellbeing message.

The adjustment in the elite player pathway through the removal of the NYC in 2018 is another step in the right direction.

When looking back on the impact of the NYC, it’s tough not to think about what toll that environment may have had on the mental state of many unprepared young players and families and whether that was all necessary.

It is a competition which undoubtedly prepared many players to make their mark in the NRL, but for others it was also a catalyst for a period of anguish and unnecessary loss.

— Rhys Jack is a former rugby league player now working with the Black Dog Institute

Lifeline’s 24 hour crisis support line is 13 11 14.

Originally published as Why NRL decision to axe National Youth Competition will save lives