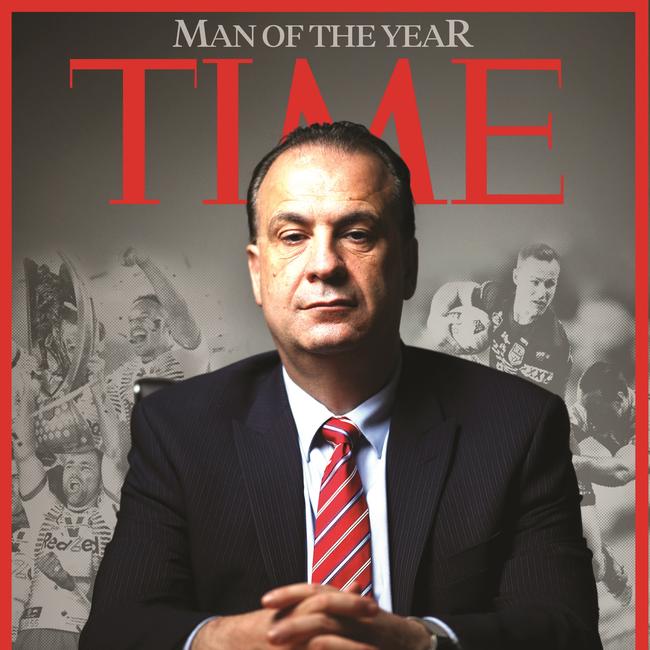

Paul Kent: How Peter V’landys and the NRL led Australia out of our COVID crisis

When rugby league needed a leader Peter V’landys stood tall, PAUL KENT details how one man rescued the game, and a nation.

NRL

Don't miss out on the headlines from NRL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It takes a special kind of irony that, already in the most unusual of years, the Man of the Year is an old undersized second-rower from Wollongong who used to hang from his clothesline as a kid in the hope it might help him grow taller.

As moves go, it was about the only wrong one he ever made.

While Peter V’landys will never be known as Too-Tall Jones, that said, nobody threw as large a shadow over Australia’s sporting landscape in this COVID year like the ARL Commission chairman.

All five-foot-nine of him.

“I look shorter because I’ve got short legs,” he once said. “Most people are 51 per cent legs and 49 per cent upper body, but I’m the opposite.”

In hindsight, it might have turned out altogether different if he had hung from the clothesline by the legs.

Still, to understand V’Landys’ impact on Australian sport is to understand there was a time, for a brief moment, that the very survival of Australian sport, as we knew it, was at stake.

Kayo is your ticket to the best sport streaming Live & On-Demand. New to Kayo? Get your 14-day free trial & start streaming instantly >

No sport was being played and most of the big sports feared going broke. Australia’s various football codes were at the mercy of the television broadcasters, already haemorrhaging themselves and in small mood for charity.

It was already accepted there would be no income from crowds, minimal income from sponsors, and when Collingwood boss Eddie McGuire dared ask Magpies members to stand by the club and forego refunds on their memberships, he got slammed.

McGuire was a victim of the panic and bad timing that underwrote the confusion not only in Australian sport at the time, but the country. There was no blueprint for surviving COVID.

Jobs were being lost. Who had time to worry about a footy club?

When broadcasters Channel 9 and Fox Sports stopped their quarterly payments, the NRL was in deep financial trouble. An abandoned season would be catastrophic because the code still had debts.

The AFL, in what was seen as prudent management at the time, ensured its long-term survival by securing a $600 million line of credit from the ANZ and NAB banks.

Labelled reckless and irresponsible by opponents of his robust ways to get NRL back amid COVID-19, Peter V’landys never flinched. He is unparalleled. https://t.co/5fzHOpjFyU

— The Daily Telegraph (@dailytelegraph) December 5, 2020

The NRL, without the collateral of a Marvel Stadium like the AFL, was in a far more precarious position. Every week without a competition was costing the game $13 million.

Then along came V’Landys, the man for a crisis.

Never convinced the NRL should have suspended its competition in the first place, almost immediately he set about getting the game running, and financial, again.

Almost immediately it drew frothing criticism from the hysterics, questioning how the NRL could dare resume its competition in apparent disregard to the health risk to the community.

But V’Landys, always a numbers man, had the advantage of logic and common sense.

He tracked the infection rates himself — which went from 22.27 per cent the day the NRL shut down to just 5.94 per cent a week later — and on the back of that began plotting a resumption to the season.

As for the attacks, which grew increasing hysterical, V’Landys stood up to them the same way he always stood up to bullies, like undersized second-rowers always did. With determined resistance.

On April 1, with the curve flattening, a phrase we hope never to have to write again, he announced Project Apollo, headed by a sceptical ARL Commissioner Wayne Pearce.

Pearce had also kept up with the news, primarily NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian’s criticisms that the NRL was pushing to return before gaining government permission.

So the attacks continued, the critics encouraged by the Premier’s quotes.

The AFL attack dogs mocked him, calling him “Push Ahead Pete”. Somebody rattled Jeff Kennett’s bitter cage and venom spat out. The AFL was used to leading Australia’s sporting tide and yet here was V’Landys, already a pain in their backside for taking on Melbourne’s racing carnival, catching them flat-footed.

What few knew was that V’Landys was already two steps ahead and had reason to be bullish.

What even the Premier did not know was that by the time Project Apollo met, V’Landys had supplied Pearce with a letter from NSW Police Commissioner Mick Fuller giving the NRL permission to resume under certain conditions, chiefly no crowds and teams based in NSW.

“As at 8 April 2020,” Fuller wrote, “the NSW Health Minister’s Directions relating to COVID-19 does not preclude the NRL from commencing a competition in the terms outlined above.”

Days earlier, Berejiklian had appointed Fuller the State Emergency Operations Controller and, while responding to the pointed questions at her press conferences, was unaware of her Commissioner’s approval.

Headed by Pearce, Project Apollo began plotting the NRL’s biosecurity protocols ahead of a return to competition.

V’Landys gave Apollo a May 28 deadline. It looked tremendously early, but once the reality of it set in, that the competition really looked like resuming, the AFL scurried to set up its own resumption while, elsewhere, the country grew encouraged by the NRL’s determination and also began slowly moving again.

Soon, we began to see a way to work through the COVID crisis.

Problems remained, though. At the same time, the NRL had to get the Warriors out of New Zealand and into Australia. The broadcast deal needed to be renegotiated. A revised season decided.

Again, on cue, the reaction bordered on hysterical.

So much so, Prime Minister Scott Morrison read the tea leaves and criticised the NRL for assuming the Warriors would be allowed entry into Australia, a decision dependent on a national cabinet meeting still to be held.

Few knew Morrison was making the same mistake as Berejiklian. He did not know that for weeks V’Landys was dealing with Foreign Minister Peter Dutton to allow the Warriors into the country. Warriors chief executive Cameron George was a former racing steward at Tamworth, where the local member was Racing Minister Kevin Anderson, who had agreed to provide the Warriors a quarantine bubble.

V’Landys was walking all the corridors of power. Rugby league has not had a leader like this since Ken Arthurson could pick up the phone to Bob Hawke in the 1980s.

Meanwhile, V’Landys began renegotiating the broadcast deal with Nine and Fox Sports, condensing months of negotiations into weeks.

Momentum for May 28 picked up, and with it the mood around the country began to shift from the early days of pessimism and worry to a genuine hope the NRL might actually pull it off and, with it, bring some normality back to our isolated lives.

Sport was leading the way for the country and V’Landys was leading the sport.

Then it almost fell apart. Project Apollo broke from a meeting and Pearce called V’Landys, telling him they had pushed the resumption back to mid-June.

This was the critical moment. Coaches Trent Robinson and Wayne Bennett, on Apollo, urged the delay so teams would have more time to prepare.

V’Landys understood their worry but he also understood the NRL’s return was bigger than a week spent running 400s, that the country was watching and the NRL’s bid to return to normality would be a metaphor for us all.

“No,” V’Landys told Pearce. “It’s May 28.”

He then called each member at Project Apollo and told them it was May 28, no argument, and that is what happened.

In less than two months, he had pulled it off.

He not only got a game back running again, but in it found something greater, finding a way when nobody was sure of anything anymore. He brought back hope.

More Coverage

Originally published as Paul Kent: How Peter V’landys and the NRL led Australia out of our COVID crisis