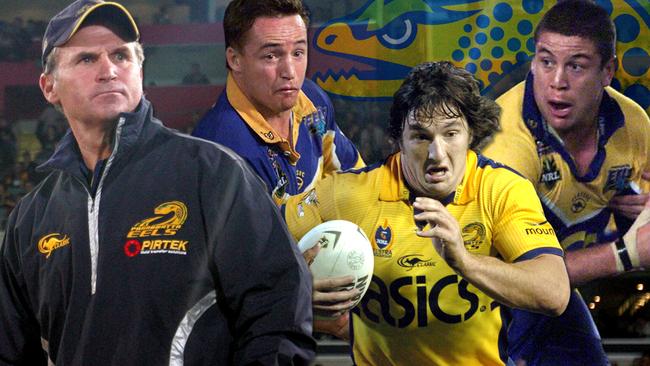

The 2001 Parramatta Eels are a mysterious team. The greatest to never win? Perhaps. But their legacy is greater than their record-breaking feats or grand final loss, writes NICK CAMPTON.

This weekend, for the first time in 20 years, Parramatta and Newcastle will meet in the NRL finals.

The humble confines of Browne Park, Rockhampton, are a world away from the cavernous Stadium Australia, where the two met in the 2001 grand final with legendary status and a premiership on the line.

To this day, the 2001 Eels are perhaps the greatest team never to win a title – but their legacy is greater than their point scoring records, or their grand final loss.

This was a team who changed the way the game is played, and who’s repercussions are still felt almost 20 years later.

This is the story of the 2001 Parramatta Eels, who helped invent the future and went within touching distance of rugby league immortality.

BUILDING A WINNING MACHINE

If you know a Parra fan, you know a Parra fan who is terrified of seeing their team collapse when the stakes are their highest.

It’s not their fault. They don’t know any different. It’s been a lean trot from 1986 to now, with enough regular trips to the business end of the season for Eels fans to know that a little bit of hope is a dangerous thing.

Case in point is the Eels at the turn of the century. They had made three preliminary finals in a row from 1998 to 2000, but not all finals runs were created equal.

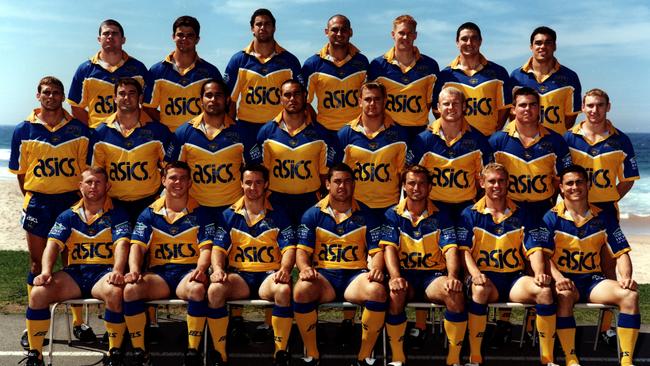

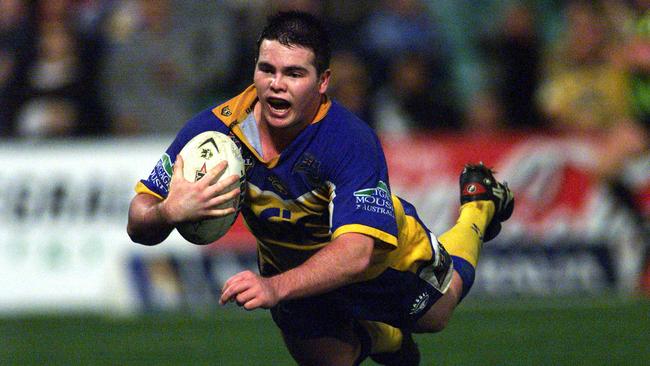

After crashing out to heavy underdogs in 1998-99 the new millennium proved to be a different story as the Eels were passed over to exciting young players like Nathan Hindmarsh, Michael Vella, Nathan Cayless, Luke Burt, Jamie Lyon, PJ Marsh and Brett Hodgson.

They finished seventh after the 2000 regular season and fought their way all the way through to the prelim before going down to eventual premiers Brisbane.

The first two losses were the end of one era, but the third was the start of something new.

“If you could start next season tomorrow, the baby Eels would be ready,” Jeff Dunne wrote in The Australian.

“The Eels dressing-room was downcast but nothing like the morgues of the past two seasons.

“The experience they gained in the past three weeks will be a great asset when it comes to dealing with a new set of expectations next time they lace the boots on and for some it will not be soon enough.”

The young brigade were starting to blossom – Hindmarsh made his Test debut at the World Cup that year – and Smith’s style was tailor made for the up and comers.

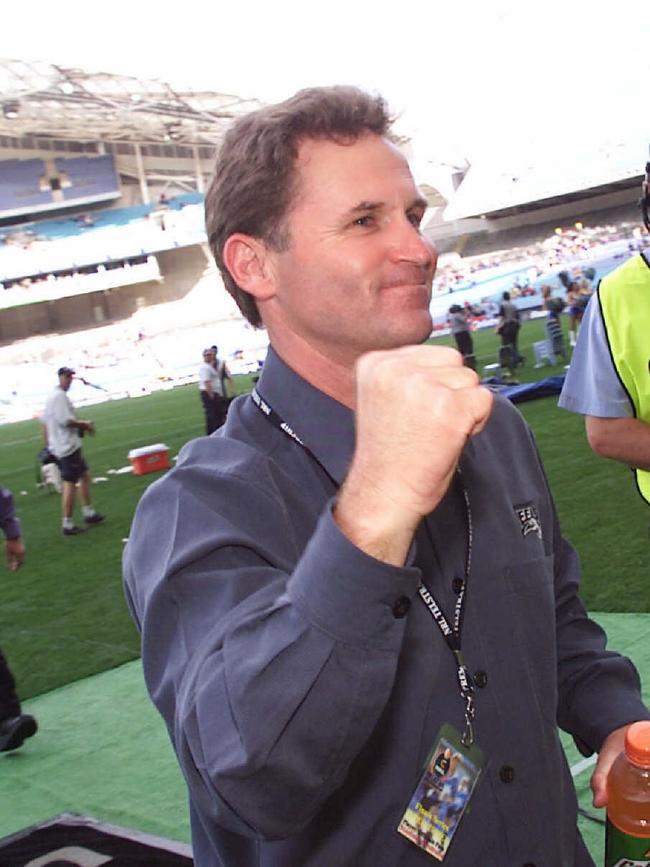

Smith was heavy on attention to detail to the point where his intensity was too much for some but the young Eels thrived under his steady hand.

“It was building. We all enjoyed playing under Brian Smith and he taught us a lot about the discipline it takes to become a proper NRL first grader,” Hindmarsh said.

“I enjoyed that sort of style. Not everyone does, but if I do something wrong I’m prepared to cop the consequences – whether that’s a spray in front of your teammates, or if it keeps happening and you’re not playing first grade anymore.

“That’s how I like to be coached. You knew where you stood with Smithy, he was the boss and you toe the line. That was it (or) you can go find another club.

“But on the flipside, the little things he taught us stayed with me through my whole career.

“Your job is never done, just because you’re in the forwards doesn’t mean you can walk because your job is done when a bomb goes up – you get back there and you help your wingers and fullback. If they spill it, you have to be there. Little things like that.

You knew where you stood with Smithy, he was the boss and you toe the line. That was it (or) you can go find another club.

“They’re not big things, they probably don’t get picked up on TV but when you’re in a team dynamic those little things count.

“You can’t switch off at all. He taught us that, and if you did you’d cop a spray in a video session and you’d never do it again.

“With Smithy, you’d know from the time the full-time siren went, you knew what you’d done wrong during that game and you knew what was going to happen in the Tuesday video session.”

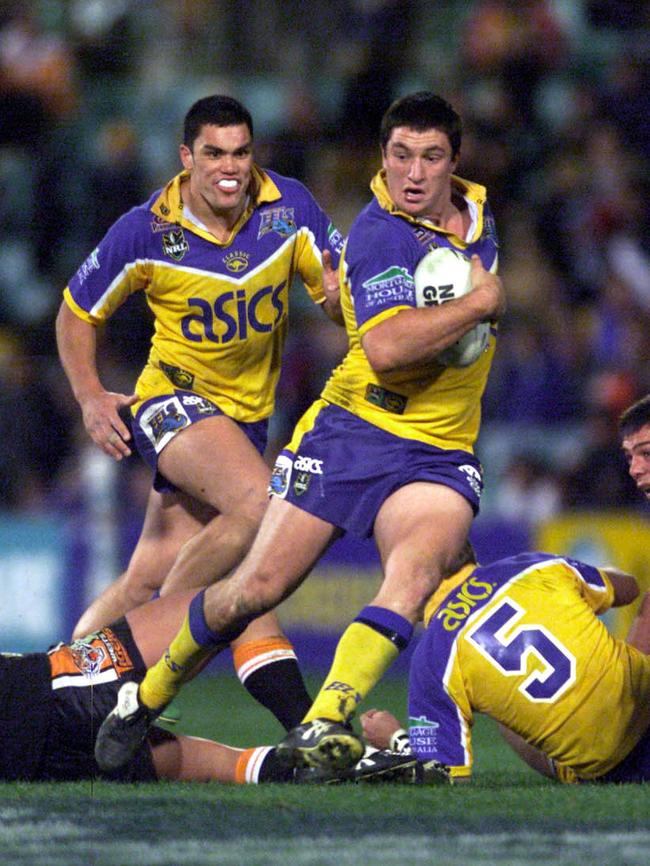

Smith and Dymock were both gone for 2001. The kids were running the show now, if they hadn’t been for some time – Cayless was the youngest captain in the club’s history at just 21.

But they were light on experience, so that’s what Smith went for with his recruits.

Michael Buettner, who began at Parramatta as a teenager before going on to stardom with North Sydney, had finished up with the Northern Eagles and was ready to come home.

“The fact Parramatta were coached by Brian Smith, who I really respected as a coach, you could see the potential they had with so many young players,” Buettner said.

“He could take players who hadn’t hit their full potential and he could bring that out in them and take them to new levels.”

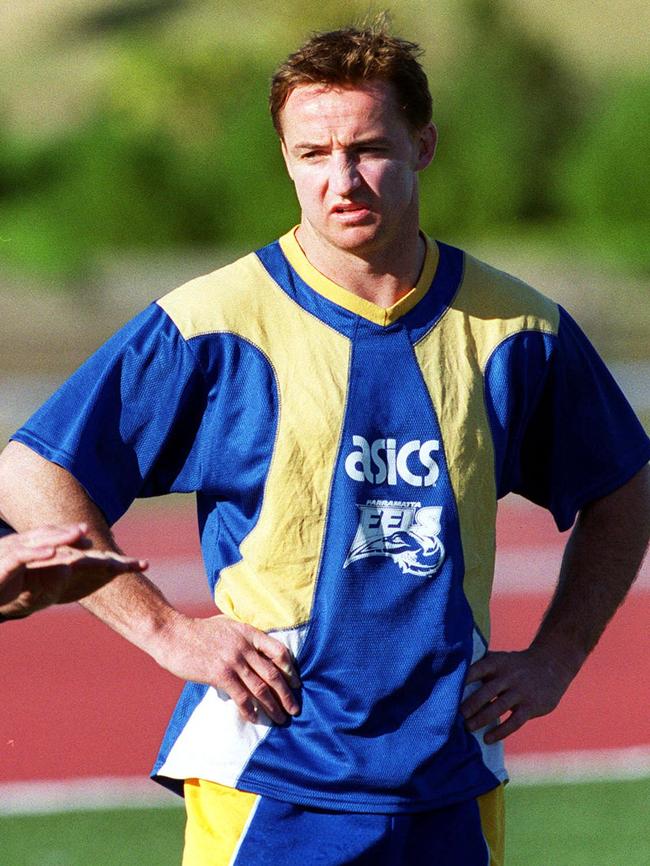

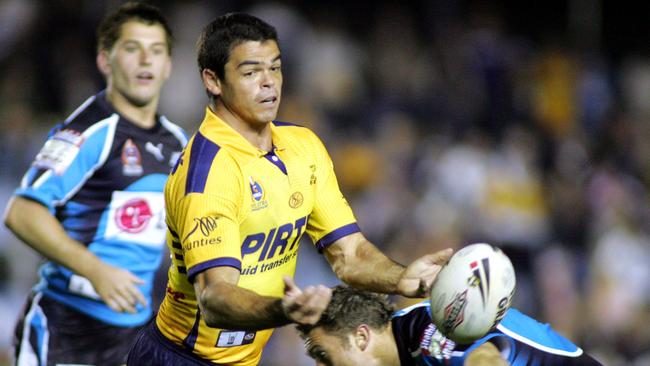

David Solomona, a gifted ball-playing backrower, arrived from the Roosters and Brad Drew came from Penrith to line up at hooker but the real prize was veteran halfback Jason Taylor.

In the late 1990s, Taylor had been one of the best halfbacks in the league and captained North Sydney to multiple preliminary finals. Despite the luckless Bears never making it to the last day of the season, Taylor was a proven performer.

He’d spent a tough 2000 season with the bastardised Northern Eagles, falling out with club powerbrokers and spending time in reserve grade, and he needed a change. More than that, he wanted one last shot at the premiership glory which had eluded him at Norths.

In the end, he hand-wrote a letter to Smith asking for a chance and that’s what he got, but there were no other promises. Marsh was earmarked as the club’s halfback of the future, and Taylor would get a chance to prove himself but little more than that.

An excellent passer and tremendous organiser with a superb kicking game, Taylor won the starting job over the pre-season but despite a 40-4 belting of Penrith in the opening match of the year, the Eels were solid early but far from the attacking juggernaut they would become.

Buettner, who had spent years in the halves with Taylor at North Sydney, and his halfback went to Smith and asked for a chance to change things.

“We played five seasons together – his game suited mine and my running game suited him,” Buettner said.

“JT and I went to him and asked for the opportunity in the halves just for a few weeks, just to see, and we had Jamie Lyon and David Vaealeki – two very capable players – in the centres and Daniel Wagon moved from five-eighth to lock.

“A lot of those young guys hadn’t had someone as dominant as JT on the park, and that took some getting used to. But the talent, the skill across the park, was phenomenal.”

Smith agreed. The old Bears boys would get their wish. The deck had been shuffled, and the cards had been played.

Parramatta dealt themselves a winning hand and they didn’t just start to create history, they began inventing the future.

WELCOME TO THE WORLD OF TOMORROW

Rugby league is addicted to nostalgia and when we look into the past quite often we don’t remember things as they actually were, but how they made us feel.

When your team has lost a game because they were dominated in the ruck it is easy to yell something about wrestling and cast your mind back to a time when that didn’t exist, whether that time actually ever happened or not.

Our memories are similarly selective when it comes to attacking football – we remember the passes that stuck and the tries that were scored, not the chances missed when things went wrong.

The 1980s were a wonderful time for everyone who was there, but on an objective level the football was not as good as it would be in the future. It might have been more fun or more enjoyable, but that doesn’t mean the play itself was any better.

Watch a game from 1981 and rugby league is almost a different sport to how it’s played today. It’s the same with matches from 1991.

But the 2001 Eels? Freeze them in carbonite for 20 years, give them a pre-season and a few questionable haircuts and they could play in 2021. Watch their games and you can see the prototype for what attacking football would become.

“I don’t think we’d be out of our element if we could jump in a time machine,” Buettner said.

“I watched a few Bears games from 1996 or 1997 and it’s horrible – we were a good side for the time, but the completion rate, the way we throw the ball around, there’s no way it works today.

“People say ‘oh, the game was great back then’ and it was and we can have short memories, but Smithy encouraged us to have a well-rounded skillbase and to go out and use it.

“I was watching the Roosters-Souths game the other way and Cody Walker set up a try for Dane Gagai.

I don’t think (that Parramatta side would) be out of our element if we could jump in a time machine. I watched a few Bears games from 1996 or 1997 and it’s horrible. – MICK BUETTNER

“There was nothing super fancy about the play, but each and every player involved knew their role and they got the defenders to do what they wanted to do.

“Walker had a short runner, a sweep runner and Gagai out a bit wider. Each one of them gave Walker an option based on what the defenders were doing.

“It looked effortless, and for Cody Walker it probably was, but if everyone isn’t doing their job it doesn’t look that good and it doesn’t work that well.

“The players know if they run it right, they give Cody Walker three options, the defenders have to make decisions and the more decisions they have to make the closer they get to making the wrong one. It might not happen in the first minute, but it will happen.

“That’s what Brian Smith brought to Parramatta, that ability to make sure everyone knows what they’re doing and their role in the system.”

Ball-playing locks have been in rugby league for a long time, but lock Daniel Wagon was jumping into first receiver and passing out the back like he’s Cameron Murray.

Fullbacks have always needed to be support players, but Brett Hodgson was sweeping around the back of decoy runners like he’s James Tedesco.

At the same time, David Solomona is throwing short balls in the middle of the field that would make Junior Paulo proud and hooker Brad Drew is engaging markers, holding up the ball and skipping across defenders with such grace you could be forgiven thinking it’s Harry Grant.

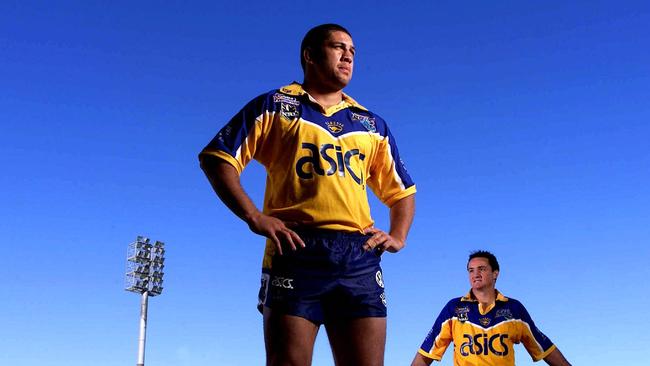

Today, many remember Hindmarsh for his defensive workrate but back in 2001 he was a David Fifita-style tearaway who parked up on the left edge and had the size and strength to burst into space but also the speed to burn the fullback.

In one game, against St George Illawarra, Hindmarsh scored a 75 metre solo try, crashing through the line and beating the cover defenders.

For most backrowers it would have been the best try of their careers. Hindmarsh did the same thing, from the same distance, five minutes into Parramatta’s next match.

He’s modest about it now, but no second-rowers are doing that today, not even tearaways like Fifita.

“It makes it a lot easier when you’re only making 13 tackles because you’re standing out there on an edge. I don’t know how we got away with that,” Hindmarsh said.

“These days there’s no way any forward makes less than 20 tackles. I was younger and fresher and out on an edge, and when you’re not making as many tackles it does make it a lot easier.”

The idea of an “edge” made up of a half, second-rower, centre and winger is now ubiquitous across the sport, but in 2001 the idea was still in its infancy.

Other teams were exploring the same patterns at the time and plenty have imitated it since, but Parramatta were the first team to not only master the pattern but build their whole team around it.

Think Cooper Cronk and Ryan Hoffman, or Johnathan Thurtson and Gavin Cooper – but first it was Jason Taylor to Hindmarsh.

“If your edge isn’t running that line hard enough, or isn’t running it properly, the entire thing breaks down because you’re not forcing the defenders to make a decision,” Hindmarsh said.

“Jason Taylor, he’s one of the best halfbacks I ever played with at the Eels because he’s make things so simple for everyone else.

“I was an edge backrower and all I had to do whenever we shifted was hit a hole, he’d either him me or he’d go out the back. It was really simple, but he’d always make the right call.”

If that sounds easy that’s because it is – rugby league is not a complex sport. The difference is in execution, and that’s where the Eels thrived.

The standard set for the Eels had an Hindmarsh brother on either edge, with Vaealiki outside Nathan and Lyon outside Ian, then having Drew and Wagon running the middle of the field.

“He’s one of the best halfbacks I ever played with at the Eels because he’s make things so simple for everyone else.” – NATHAN HINDMARSH on playing with Jason Taylor.

Brett Hodgson tore through the middle of the field or bobbed up on either edge, much as fullbacks do today, while Taylor played both sides of the ruck the classic halfback style that disappeared for a while but has now come back into vogue.

“JT was very good at controlling the game, managing the game and directing a team around the park, getting them to the right position,” Beuttner said.

“All these kids had all this attacking flair but because they’d been under Brian Smith they were so smart with their game awareness and they had the skill to match that.

“There’s similarities now with Penrith, with the skill level and the way they play, they remind me of us a lot.

“The halves are different, (Nathan) Cleary and (Jarome) Luai are still very young, but it’s a group of kids who all came through together.”

Throw in the offloading of Cayless and Andrew Ryan, the skill of Solomona and the raw athleticism of Vella and there were threats everywhere. The knives were always out and there were so many of them Parramatta stretched defences until they were at breaking point, then they broke them.

With Taylor’s and Drew’s passing game, they stretched the field with ease like the best modern-day teams do and just like 2021, rule changes took their already effective style and kicked it into another universe.

PUT IT ON THE RECORD

From 1996 until 2000, a team could make as many changes with their four substitute players as they desired. In the 1998 grand final, Brisbane made 34 changes while Canterbury made a whopping 38.

Things reached the point of farce – in a 1999 semi-final against the Dragons, Roosters utility Graham Appo came on for Adrian Lam while the kick-off was still in the air – and it was clear to everyone that it could not continue to be this way.

So the powers that be handed down the decree that from 2001 onwards, changes would be restricted to just 12 per side.

It was aimed at bringing fatigue back into the game, bringing back the little man and opening up an attacking game that, some said, had become staid and predictable.

When the effect of these rules proved to be a lot of blowout scores, a serious gap between the best teams in the competition and the stragglers this was excused away by blaming teams for poor roster management, or focusing on a lack of talent and fitness among the stragglers. The idea that making a dramatic shift to the fundamental order of the game, and watching those changes run out in real time, was ignored.

Some times rose in the new world and some fell, but if a team had the right pieces, if they had attacking skill all across the park, a fearsome forward pack and a fast backline with a spine bold enough to wield it they could run and gun their way to historic attacking highs as teams who were built for the old ways were hit incredibly hard.

If all of that sounds familiar, it should. It’s the same situation the league is in now after the radical six-again changes.

The 2001 Eels have been joined in point scoring history by the 2021 Storm. Along with the 1935 Roosters, a team so ancient they are truly from another realm, the three hold most of the league’s season-long attacking records.

When the game is changed on such a molecular level as it was in 2001 and 2021, it’s time to throw away the compass when it comes to tracking records, because it all only heads in one direction.

Parramatta are still first all-time for points scored in a regular season (839) and total points scored in a season (943) and are third for average points per game in a regular season (32.3, compared to Melbourne’s 34).

Parramatta boast the fourth-best points differential of all time with 433 while the Storm are first with 499. They matched the Roosters with six scores of more than 50 points and their 159 tries are the most of any team in a regular season ever.

And just like the 2021 Storm, the Eels didn’t have the space in the record books all to themselves. The Rabbitohs ran Melbourne mighty close this year, ending the season with 755 points – just 22 behind the Storm.

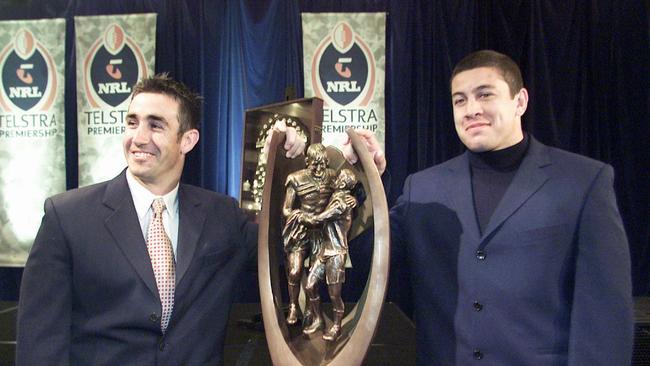

Parra had more of a cushion ahead of their nearest rivals, Newcastle, who finished with 782 points. The Eels got the shine, and rightfully so, but those Knights were, at the time, the second-most prolific attacking team in NRL history.

Having a season that boasts one all-time attacking team is a delight. Having two is a twist of fate. Having them meet in the grand final, with a premiership and history and the chance to live forever as the best to ever do it on the line? That’s destiny.

ACCEPTABLE IN THE 80S

Rugby league is built on hype but there is no hype like Parramatta hype.

Courtesy of their four premiership victories in six years back in the 1980s, the Eels are one of the most well-supported teams in the league.

Whenever Parramatta start going well and there seems to be a chance of ending the club’s premiership drought, which stretches all the way back to 1986 and is the longest of any club in the league, the blue and gold faithful all come out of the woodwork.

Back in 2001 the wait had only been 15 years, but time passed slower back then and it felt like far longer.

Once the Eels started picking up steam that season, and courtesy of their breathtaking attacking football, comparisons to the glorious teams of 20 years before came thick and fast.

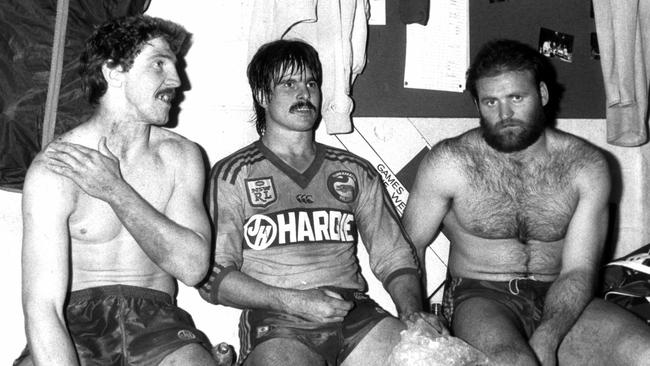

In August of that year, The Daily Telegraph commissioned a five-man panel consisting of Ritchie, Peter Frilingos and legendary players Arthur Beetson, Rod Reddy and Johnny Raper to decide if the 2001 Eels were better than the 1983 Parramatta side, considered the best of the club’s premiership teams.

Ritchie, Frilingos and Beetson went for the old guard, but Raper and Reddy both backed the modern boys.

“The current side has more skill one through 17 over the 80 minutes, that’s the difference,” Reddy said.

The weight of such history is heavy, but Hindmarsh says the Eels never felt it as a burden.

“It was a great feeling. Everyone has the same feeling for their own club but Parramatta, because of the success they had in the 80s, have a supporter base that just grew and grew.

“I work with Fletch (Bryan Fletcher) a lot and he always says there’s bloody Parra fans everywhere, and that’s because of the 80s. Wherever we go, even in Brisbane or around Queensland, you’ll find a Parra jersey somewhere.

“I loved it. It was a great feeling for the city of Parramatta. Out here we can get the rough end of the stick, but when your footy team is flying there’s no better place to be.

“We’d always think of it as that’s the reason we have such a great fanbase, because of what happened in the 80s.

“We enjoyed the fact they had all that success. There was never any added pressure to win a comp because of that success.”

Watching the Eels week to week in 2001, it was easy to get carried away.

When they beat the Northern Eagles shortly before the finals, coach Peter Sharp declared they couldn’t be beaten.

“That’s only my opinion,” Sharp said.

“I thought physically they gave us the rounds of the kitchen. They throw that much footy at you. They just wear you down towards the end of the game.”

They were good, but with the relentless Smith in charge, they were always striving to get better.

Drew, a capable hooker/halfback during his eight prior seasons with Penrith, caught fire and was named Dally M hooker of the year and was at the heart of a three-game streak in July where the Eels scored 166 points.

In the final one of those games, a 62-0 belting of North Queensland, Taylor broke Daryl Halligan’s record for most points scored in first grade.

The playmaker was rejuvenated, enjoying the best season of his career as were so many of the Eels, because of Smith’s attention to detail.

“This might seem silly, but when I went back there it was my ninth season in first grade and he taught me how to play footy,” Buettner said.

“That’s not being disrespectful to the coaches I had previously, but he just had this approach where he broke the game down and highlighted specifically what you had to work on and he’d explain why these things were important, what they could offer to the team, what it would offer you as an individual.

“I look back on that era where Brian was at Parramatta and they were criticised sometimes for the players who left, but they all left far superior players.

“It’s not unlike players at the Storm or Roosters now, or the Panthers over the next few years – they’re in a system and are coached so well that once they leave they become major assets to other teams. He had that ability.”

Sometimes, Smith’s preparation verged beyond what even other coaches would consider normal.

One week, he allowed assistant coaches Rod Reddy and Alan Wilson to run every training session, just in case he fell ill during the finals. The tinkering, the obsession with improvement, never stopped.

In the lead up to the final round clash with the Roosters, which the Eels won 27-26, he claimed he had chased off three men trying to videotape a Parramatta training session.

Seven days later the Warriors 56-12 in the first week of the playoffs, the highest score in finals history to that point, Smith benched forward Alex Chan uninjured and his team played the final 12 minutes with 11 players – just in case someone copped an untimely sin-binning somewhere down the line.

“He would always try something new. You never know what scenario you’ll face in the next game, so he’d always prepare and he was always a step ahead,” Hindmarsh said.

“That’s how he did things, and he was always willing to try different things.”

After earning a week off, Lyon starred in a nervous 24-16 win over Brisbane in the preliminary final and the Eels, at last, were back at the season’s biggest day.

But despite finally clearing the hurdle they’d fallen at three years in a row, and with the crown finally in reach, the job was not done.

“They brought out T-shirts that said ‘2001 Grand Finalists’ on them but I was really reluctant to put them on,” Hindmarsh said.

“Some blokes were putting them on but I said ‘I can’t wear this, we’ve made the big dance but we haven’t won it yet’.

“It was the same in 2009, with all the photos me and Cayless did, they asked us to hold the trophy and I said we wouldn’t do it.

“I wouldn’t for a minute say we were arrogant or overconfident, because Brian Smith would have never let us. There’s no getting ahead of yourself with Brian Smith.”

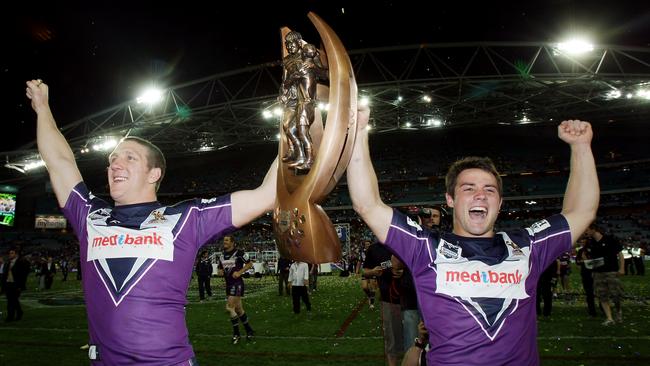

PERFECT... UNTIL IT WASN’T

There is a story Andrew Johns tells about the 2001 grand final breakfast, and he’s told it many times but the basic premise is always the same – that he knew, from the second he saw the Eels, that the Knights had them covered.

Parramatta looked nervous. Uptight. Painfully aware of the weight of the moment and what was at stake.

Newcastle understood the gravity of the situation just as well, but they players who’d appeared in the 1997 grand final, as well as a host of Test and Origin stars. They knew how to handle the big occasions.

While Brian Smith had coached St George to grand final appearances in 1992 and 1993, just one player – Solomona – had been there before.

And the Eels were young. The average age of the squad was 23. Even Taylor, the old man of the side, was just 30, and if they looked nervous it’s because they were.

“We were still quite young and it was the first grand final for a few of us, we were very nervous,” Hindmarsh remembers.

“It was a bit of a blur. It was a busy week, an exciting week, and I remember the smell of the air because it was spring, getting a bit warmer, and all your little niggling injuries disappeared for that week.”

Smith took the side into camp down in Wollongong until the Wednesday, in an attempt to settle things down. After losing back-to-back grand finals with the Dragons in 1992-93, he was leaving nothing to chance.

The 91,000 tickets for the first ever night grand final were snapped up by midweek, one punter put $70,000 on the Eels at $1.40 while the Knights, still respected courtesy of their many stars and with Johns as their focal point, were relegated to $2.75 outsiders.

The Novocastrians had finished third in the regular season, and were near as potent as the Eels, but hadn’t enjoyed such consistency.

A down period around the Origin series, where they lost four straight games, and another three-match losing streak had many doubting the team’s premiership credentials under rookie coach Michael Hagan.

And while the Knights could rack up points with the best of them, defensively they were shaky. No team has ever won the premiership and conceded 50 points in the same year, but the Knights came perilously close when they conceded 49 against the Sharks in Round 22.

But they steadied, mainly on the back of superb play from Johns and backrower Ben Kennedy, and knocked off the Roosters and Cronulla to earn the right to challenge the Eels.

Unless you were one of the red and blue horde howling down the freeway from the Hunter as part of a fleet of Sid Fogg buses, Parramatta were the pick. They had won 21 of their last 22 and had broken so many records it was difficult to keep track of them all.

It was time to take the last step, into greatness, into history, into the heavens. Losing was not possible, not for these Eels, but if they had to lose surely they would go down swinging in a point-scoring bloodbath for the ages where two of the greatest attacking teams collided in a kamikaze battle where there would be no winners, only survivors.

But there was no mighty crescendo, just a cloud of dust, a few Parramatta screams, some points on the board early and the game was gone. The 91,000 fans saw a legend die in front of them.

The Knights pulled off a blitzkrieg in the first half, running out to an incredible 24-0 lead after 31 minutes that even the most pessimistic Parra fan wouldn’t have thought possible, and any chance of the Eels claiming their status as the greatest team of all time.

“They had the perfect half of football. They had a game plan to get at the halves – I think I made almost 40 tackles. That’s ridiculous, I usually wouldn’t do 40 tackles in four games,” Buettner said.

“Steve Simpson and Ben Kennedy kept hammering us on the edges, but there were a couple of chances in the first half that we just missed.

“Luke Burt got a pass from Hindy that was just a touch in front of him right in the corner, Andrew Ryan got held up by Steve Simpson in what was an absolute miracle. Even if it was 24-12 at halftime, that’s a different story.

“But I have to say, when we went in at halftime there was still that belief we could come back.

“Because of our skill and ability we genuinely believed we could make history and come back.”

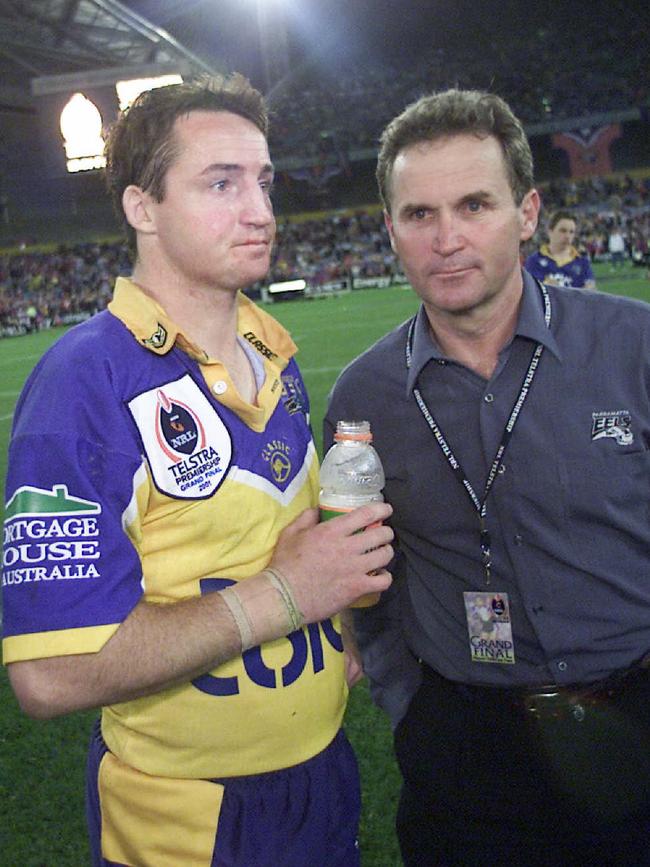

Despite the Eels scoring first in the second half when Hodgson went over in the 56th minute, Hindmarsh wasn’t so optimistic.

“It was hard not to think it was over. I remember sitting in the sheds thinking that I know we’ve got a good team, but I don’t think we have the time to do it. It was hard not to think it was gone,” Hindmarsh said.

“There’s a moment where Joey puts a kick in and the bounce Timana Tahu gets….look, you could kick it 100 times and I don’t care how good Joey Johns is, that was….but Timana had to be there to get it, didn’t he? And he was.

“That kind of summed up our night, that kick.”

That stretched the score to 30-6. Parramatta fought to the end, finishing just six points behind in a 30-24 upset, but were never truly back in the hunt.

It must have been so painful, to see their comeback and half-believe it was possible. Sometimes the greatest cruelty of all is a little bit of hope.

“Whether it was nerves or their gameplan, there were certain players they were looking to target and they did a good job of it and we had no answers,” Hindmarsh said.

“It was a yuck grand final, put it that way, and that’s the one that kills me.

“That was our opportunity, I thought we were such a good side and we loved playing with each other. The disappointing thing was we didn’t get it right on the day.”

Those Eels never reached such heights again. Taylor stuck to his plan and retired, and the Eels missed him badly in 2002 as they crashed to sixth. Until the game was once again fractured by drastic rule changes this year, nobody came close to their attacking records.

Buettner left at the end of 2002 for the Tigers and by 2005, when the Eels again won the minor premiership, only six players were left from the team that made so much history.

Hindmarsh, as ever, was the last man out the door along with Luke Burt when the pair retired together at the end of 2012.

Smith was long gone by then, sacked in 2006 after a run of poor results. He never did win that premiership, and is remembered – unfairly – more for his four grand final losses than for taking four teams to the brink of a premiership.

In the end his ultimate legacy is one of style and substance – now everybody plays at least a little bit like the 2001 Eels. That’s not something you can hang in a leagues club or put on a trophy, but it’s not nothing either. There is personal glory in victory and professional glory in innovation.

Unless you’re almost 50 or older, the 2001 Eels are as close the glory of the 1980s as you can get – these days, as many Parramatta people talk about the premierships they didn’t win as opposed to the ones they did.

The Parramatta faithful are still waiting for a new team to join the old legends and for a blue and gold sun to rise over paradise. When they do they’ll go so wild that burning down Cumberland Oval will seem tame.

And when it does happen, be it this year, the next or further down the line, you can bet the Eels team that does it will be playing just a little bit like it’s 2001.

“I describe that two week period, the week of the grand final and the week after, as the best two weeks of my career – and we bloody lost!,” Buettner said.

“I can’t imagine how good it could have been had we won.”

Roosters’ 132kg teen giant snapped up by NFL Academy

Roosters junior Talby Smith is just 15-years-old but is already 198cm and heavier than any NRL player – and he’s still growing. Now, the “one of a kind athlete” has his taken first step towards a potential NFL career.

Future is now: Young guns that eliminated teams must let play

With seven rounds left in the regular season, there are seven clubs who are either out, or almost out, of the finals race. These are the players who should be getting time in first grade before the end of the season.