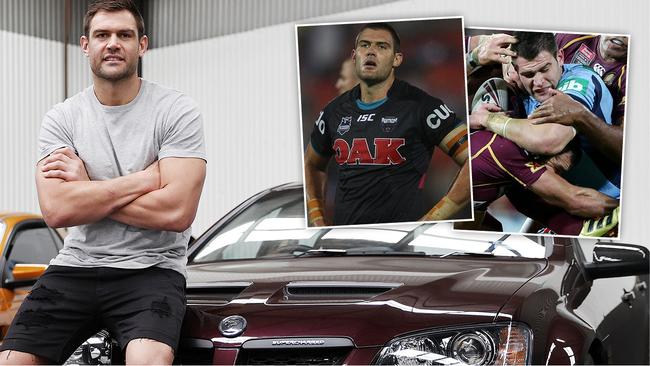

Life after NRL: Former star Tim Grant lifts lid on painkiller secret

Former Panther Tim Grant says he retired to ensure he wasn’t taking the spot of a young gun, but would things have been different had he known what was to come?

NRL

Don't miss out on the headlines from NRL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

We stop the interview at 7pm.

“Can we pick it up tomorrow,” Tim Grant asked. “I need to get to bed. I start work at 5.30am.”

Which means the former State of Origin star will be up at 3.15am, in his car at 3.45 and, after the 90km drive from Penrith to Helensburgh, he will arrive ready for work by 5.15am.

We suggest a time for the next interview

“Na,” Grant said. “I’ll still be working mate. Call me at 6pm. I’ll be in the car by then driving home so I’ll have some time.”

We know we will not be able to reschedule. Grant’s phone will be off and, in a locker, long before we wake. The retired NRL star can’t take it where he is going.

“Yeah it would set off an explosion,” Grant says. “You can’t even wear a watch let alone take a phone.”

Watch every 2021 NRL Telstra Finals Series match before Grand Final. Live & Ad-Break Free on Kayo. New to Kayo? Try 14-days free >

There would be no signal anyway. Not where he is going. Not 300m below.

Rewind 10 years and Grant has just signed a six-year deal with the Penrith Panthers for over $3m.

“I would have laughed at you had you told me I would be working in a mine when I was 32,” Grant said.

“I remember all the old blokes telling me to enjoy every moment. To plan and make the most of it. That it would be over before I knew it. But I never thought that rugby league would not be a part of my life.”

A HERO CALLED CHIEF

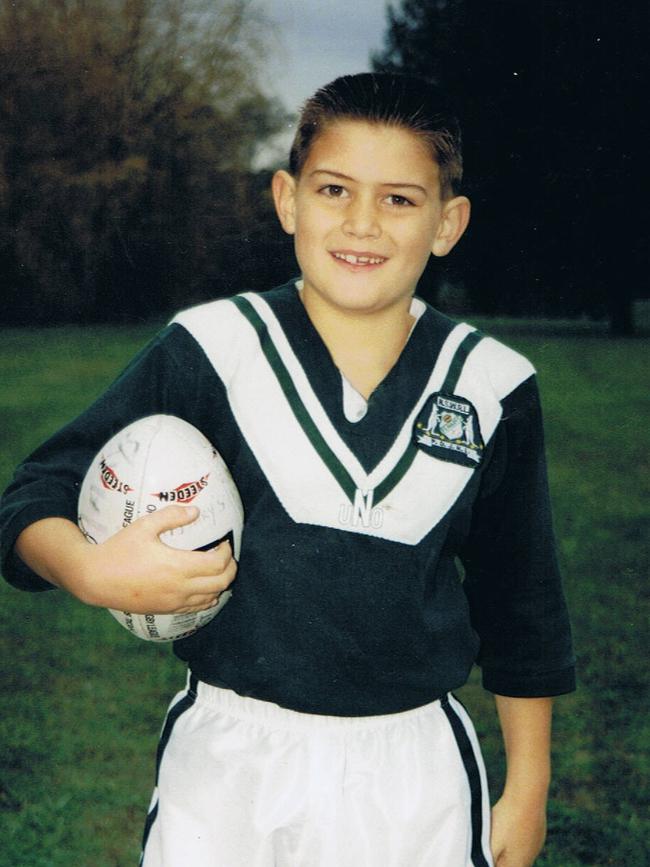

Grant’s NRL dream was born on the back seat of his family car.

“Are we there yet?” he would ask even before hitting the F1. “We just left Penrith,” his mother Kim would reply.

“Don’t worry. We won’t miss the game.”

Dressed from head to toe in red and blue, his well-worn “No. 10” jersey now a little too tight, the six-year-old returned to his daydream.

“I used to imagine playing alongside the Chief (Paul Harragon),” Grant said.

“I was born and bred in Penrith but the Knights were my team and the Chief was my man.”

Grant has always loved rugby league, even though, as you will soon read, rugby league has not always loved him.

“I was obsessed with it,” Grant said. “And obsessed with the Knights. So much so that Mum and Dad ended up changing the destination of all our family trips to Newcastle so I could watch the Knights.”

Grant can only ever remember wanting to become one thing; a football player of course.

“I think Mum was a bit worried at first because she started me off in soccer,” Grant said.

“But that didn’t last long because I hated it. I ran off the field a couple of minutes into my first game and said I wasn’t going back on.”

Grant would have to wait another two years before his Mum let him play rugby league.

“Yeah loved it straight away,” Grant said of his first match for St Mary’s Penrith.

“I wouldn’t say I was good back then but it didn’t stop me from dreaming about playing in the NRL.”

And that dream would soon come true, borrowed boots and all.

I CAN’T WEAR THESE

Grant put down the dumbbell when he was summonsed.

“Hey Timmy,” Panthers coach Matt Elliott called. “You got a minute?”

The young prop wondered what he had done wrong as he walked towards Elliott.

“Take a seat,” Elliott said.

There weren’t any.

“So I sat on a shoulder press machine,” Grant said. “Which I almost fell off when he told me I would be making my debut. I was stunned.”

So much so that the now 19-year-old did not even have boots.

“Well not boots I could wear in the NRL,” Grant said. “I only had one pair back then and they were bright red. They were okay for playing reserve grade but there was no way I could have worn them in the NRL. They were way too flashy for a young bloke to get away with. “

Grant walked into the sheds holding his bright red boots.

“Hey does anyone have a spare pair of boots?” Grant asked. “There is no way I am wearing these.”

The veteran NRL players, stars like Craig Gower and Luke Priddis, laughed and shook their heads.

“Oh they will be coming for you,” one of them said.

The behemoth named Puletua was thundering about in a locker.

“Size 14?” Puletua said as he pulled out a box.

Grant played nine NRL games in a row after making his debut, wearing the hand-me down, and completely black boots, in every match.

“Matty (Elliott) told me to enjoy every moment,” Grant said. “He told me that my career would not last forever. I was like ‘yeah whatever’.”

THE RATCHET CLAUSE

Grant signed what would become one of the most controversial contracts in Penrith history in 2010 after establishing himself as one of the best young props in the game.

It started as a five-year deal worth $3m, but became a six-year deal that was worth … well even Grant can’t give you a figure.

“I honestly can’t tell you what it was worth because of the way it was structured,” Grant said.

“It was talked about in terms of the percentages instead of dollars because my manager did a great job and had a ratchet clause inserted which meant it would go up every time the salary cap went up.”

The contract was also littered with bonuses and incentives, which once earned, would become part of his base deal.

The contract became even more complicated when Grant agreed to take a pay-cut.

“Timana Tahu was coming to the club in 2011 and they didn’t have enough salary cap space to sign him,” Grant said. “They came to me and asked me if they could take some money from the first year of my deal and give it to me at the end of my deal.”

And with that Grant had a doomsday deal – a back-ended contract with a ratchet clause.

“And I thought I was doing them a favour,” Grant said.

Grant had no idea that his dream deal was about to become a nightmare.

“It started with rumours that I was being shopped around,” Grant said. “Apparently the club was in salary cap trouble and they were trying to offload the blokes on good money. I just ignored it. If anything, I thought I was good value for money.”

But the rumours would not go away.

“I knew there was something to it when the club asked if they could remove the ratchet clause from my contract,” Grant said. “I said no because as far as I was concerned I was entitled to it and didn’t think they would ever brush me for a blow-in.”

Or would they?

“It started getting to me after a while,” Grant said. “I eventually got the shits with the people that were questioning my pay packet and with the club for shopping me around. And my football started to suffer.”

Grant reluctantly agreed to quit the club at the end of 2014.

“It was no longer the place I fell in love with,” Grant said. “I had gotten a really good offer from the Rabbitohs and after meeting Michael Maguire I decided to take it”

Grant said goodbye to both his mates and his innocence when he left Penrith.

“I had learned rugby league was a business,” Grant said. “And I was just a product.”

Grant had no idea that the ordeal had scarred him for life. Not then anyway.

GROUNDHOG DAY

Grant had only just moved into the house he had built at Chifley when it happened again.

“I’d just finished my first year with Souths when Madge (Michael Maguire) told me they were having problems,” Grant said.

“Apparently they had signed Sam Burgess without having a good look at the books. Madge told me he had been shopping players to clear the salary cap space they needed but no-one was interested in them. I was told I didn’t have to go but there was a big opportunity for me at the Tigers.

“Anyway I had learned my lesson at the Panthers and knew this game was just a business, so I went and had a chat with Jason Taylor and Justin Pascoe. I liked where they were heading and what they were offering.”

So Timmy became a Tiger.

“It wasn’t as hard as leaving Penrith to go to Souths,” Grant said.

“I knew I was just a commodity so I decided to treat it as a business too. The deal was going to be better for me financially, so I took it. It’s sad to think that is what the game has become but that’s the reality.”

Grant dismisses the suggestion that the disruption of having three clubs in three years affected his form. Or created a fear of failure that would perfectly explain what comes next.

DAMAGE DONE

Two years later and Grant is sitting in a clinic about to get a CT scan.

“I thought you guys played tonight?” asked the radiologist. “Yeah we do,” Grant said.

“Oh,” she said. “Just a precaution I hope.”

Grant nodded even though he knew he had three broken ribs.

Grant wasn’t here to be diagnosed through the scan. He was here to be injected with painkillers but they were too dangerous, because of the location of his injury, to be administered without being guided by the live pictures provided by a CT scan.

“They could have punctured my lung with the needle or hit an organ,” Grant said.

“I had three broken ribs which should have ruled me out for about eight weeks.

“But I decided I could play through the injury if I was given a painkilling injection before I played.”

“So that’s what I did. Before every match for the next eight weeks.”

Grant had to get the injections on game day because the painkillers only last for about six hours.

“It didn’t work at all before one match,” Grant said.

But still he played. Grant gave zero thought to his future or the damage he was doing to his body.

“I didn’t think about anything except doing what I had to do to play football,” Grant said.

“I learned to ignore my body. I thought it was normal to get up in the morning and take a few tramadol just so I could go to training.

“I have been told that tramadol is a hard drug that should only be used after surgery but I scoffed them just to be able to do my job. I don’t think I was ever addicted. I never took them to get a buzz. I only took them for pain relief.

“But yeah, I always had a cup full of them on my fridge and I took them like they were Panadol.”

Grant pauses when asked whether being “off-loaded” by his last two clubs played a part in his decision to be injected with pre-match painkillers, which led to permanent rib damage, and exposed himself each time to the radiation of a CT scan.

“All three ribs have calcified to the point where they are sticking out of my chest I can’t lie on my side for more than an hour because of the pain,” he said.

“It was more because I feared letting down the boys. Letting myself down. And it was always my choice. If I said I couldn’t play they wouldn’t have made me do it. I didn’t feel like I was being abused. I abused myself.”

THE LAST TACKLE

Back at Penrith after signing a homecoming deal to re-join the Panthers, Grant lined up the fleet-footed Manly winger and steeled himself for the hit. But Abbas Miski first swerved and then stepped.

“I had to throw out my arm to make the tackle and I got him with my fingertips,” Grant said.

“It ripped my arm right back but I managed to get him down.”

Grant ignored the sound of muscle being torn from bone and completed the tackle.

“I had no idea that it was the last tackle I would ever make,” Grant said.

Grant was forced to retire from rugby league when scans confirmed his pectoral had been torn.

“I was enjoying my football and playing well,” Grant said. “Even with the injury I thought I would get another deal. The thought of retirement hadn’t even entered my head. To be honest I thought I had at least another two years left in me.”

And this is where the story takes a turn. While Grant will not go into details, it is understood that he may not have agreed to retire if it was not for the sponsorship job the Panthers had promised him when he signed his deal.

“Look there was a job I thought I had lined up but that isn’t the reason I retired,” Grant said. “At the end of the day I made that decision (to retire) because I didn’t want to stand in the way of a young bloke getting his shot.”

The day he thought would never come had suddenly arrived. But that was okay. He knew what he was going to do with his life. He was going to work for the Panthers.

“I thought I had things worked out,” Grant said.

“But turns out the sponsorship job didn’t happen. I was suddenly in the position where I had nothing and did not know what I was going to do. I had to ask myself “who am I now?”. Rugby league had been my life. I didn’t know who I was without rugby league.”

Grant began assessing his options.

“I knew I was never going to find anything that I loved as much as rugby league,” Grant said.

“And that was depressing. Sure there might be things I would like but it would never be like rugby league. I was never going to get the high that I got after winning a game of footy.

“It leaves a big hole.

“I understand why some people turn to alcohol or drugs. They search for that rush. But I have never been interested and it is not my thing.

“My Mum got quite worried about me about four weeks after I retired. I was lost. I had been told what to wear, what to say, what to eat ever since I went full-time. That routine and regiment was gone. I was waiting for someone to tell me what to do. What goal to chase. I had nothing to strive for. I was 31 but felt like I was washed up.“

300 METRES DOWN

IT wasn’t quite the same as running head first into a Victor Radley tackle but it was a shot of adrenaline all the same.

“Holy shit,” Grant said as the metal cage he had just stepped into dropped.

Dressed from head to toe in hi-vis safety gear, a life saving breathing apparatus strapped to his belt and wearing a hard-hat equipped with a light, Grant was 300m below the surface when he stepped out of the cage.

“It was a whole new world,” Grant said. “I had never seen anything like it. And yeah, it was exciting, not just the environment but also because I was learning something new.”

Grant began a new career as a miner six months after his rugby league retirement.

“That first day was pretty nerve racking,” Grant said.

“I was given my locker and then told to take my clean clothes off on the clean side of the room and then put my work gear on over on the dirty side.”

Grant was a little concerned at first when he was given a device called a “rescuer”.

“It is a device that gives you 45 minutes of clean air in case something goes wrong,” Grant said.

“You have to carry it with you at all times.”

Grant has now spent the past two years working as far as 600m underground as a miner.

“I do what is called secondary support,” Grant said. “I put bolts and ribs into the walls to reinforce them. I usually work nightshift, which is from 5.30pm to 5.30am but I have also picked up some day shifts over the last few weeks.”

Grant is not working in a mine because he needs the money.

“I was pretty lucky because I have always been well paid and was sensible with my money,” Grant said.

“I don’t have to work as a miner but an opportunity arose and I took it because I needed to do something to replace the hole left by rugby league. I love the banter with the boys and enjoy the work. I am not sure I will do it forever but It has been great for me so far.”

Working a 36-hour week in the mines, Grant also moonlights as a used-car salesman.

“My passion is muscle cars,” Grant said. “I have had a few over the years and I was lucky enough to meet Shane Brennan through his brother Garth. Shane is the man when it comes to everything muscle cars and he has been teaching me the business. Hopefully one day I can make something out of it.”

Grant is telling his story in the hopes of helping the next generation plan for life after league.

“I hate to admit it but I am now that old bloke I wouldn’t listen to,” Grant said.

“And I am not going to tell anyone what to do but if I had my time again I would have gotten myself more hands-on experience. I would have been more prepared and would have known exactly what I was going to do. In hindsight I should have learned the car business while I was playing. Not now. And I think the NRL needs to step up and help organise some on the job training.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Life after NRL: Former star Tim Grant lifts lid on painkiller secret