AFL v NRL: Helicopter flight that shocked Peter V’landys

The woes at Parramatta and Penrith opened a crack that GWS Giants rushed to fill. One helicopter ride revealed how fast the AFL moved.

NRL

Don't miss out on the headlines from NRL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ARL Commission chair Peter V’landys caught a helicopter flight over NSW’s Hunter Valley a few weeks back. What he saw shocked him.

“Complacency leads to failure,” V’landys said.

“People who think it is just going to happen are never successful. You need to put the work into it to get the results. It is a wake-up call how we have been infiltrated and whichever way you look at it, they (the AFL) have been successful.

“I went up in a helicopter (recently) and I was shocked at the number of AFL fields compared to rugby league fields.

“It was an eye-opener. It highlighted to me that they have made more progress than people give them credit. We are not going to take our eye off the ball here.

“People think it lands in their lap but it doesn’t.

“It’s not just western Sydney, it is everywhere. If someone comes along and does it better and brighter and works harder, they will get the results.”

Watch every 2021 NRL Telstra Finals Series match before Grand Final. Live & Ad-Break Free on Kayo. New to Kayo? Try 14-days free >

BIGGER & BETTER

Truth be told, complacency rather than the AFL has been the NRL’s greatest enemy in western Sydney. The ‘Heartland Project’ — the document pieced together on behalf of the ARL Commission a decade ago — made that eminently clear.

Parramatta spent the early years of GWS’s existence fighting an internal war. The Eels were regarded as a powerhouse in western Sydney but they didn’t act like it. They were a dysfunctional rabble, their progress on the field hampered by their failure to find stability off it.

The club reached its nadir in 2016 when the salary cap scandal tore it asunder. What happened next has been well-documented to the point where chief executive Jim Sarantinos is sick of talking about it.

It is worth, however, noting the comments of former ARL Commission chair John Grant when he attended the Ken Thornett Medal at the end of the 2016 season.

Grant still has the speech on his computer, having told a room full of players, officials and sponsors that they needed to use the disaster to regenerate the club.

“Having said that, we only had one agenda … and that was to restore the Parramatta club to the powerhouse position in the game that it should hold and that this game in western Sydney needs it to hold,” he told the room that night.

“So, can I take this opportunity to encourage all of you ... fans, members, staff, volunteers, sponsors and players to actively and overtly support the agenda for change, for a fresh start; and to discard forever the factional rivalries and backroom bickering that have brought this great club to its knees.”

That challenge has been more than met.

“We’re a long way removed from that,” Sarantinos said.

“That is well and truly in the rear-view mirror. We are very stable from a board perspective; the club is doing well commercially; there are still great opportunities with the growth of western Sydney, not just the population but with the growth of business.

“There is all these opportunities that are going to be in front of us over the next 10 or 20 years and we need to be well-positioned to take advantage of that.”

There was an anonymous quote in the ‘Heartland Project’ that resonates in the present environment. It illustrates just how far the Eels have come in a relatively short time.

“My national brand logo just can’t sit on an NRL club jersey alongside ‘Joe’s Smash Repairs’,” it said.

The Eels’ portfolio of sponsors now includes brands such as McDonald’s, Subaru and Taubmans.

Crucially, there remains a place for Joe’s Smash Repairs at a club that will edge closer to a grand-final appearance for the first time in more than a decade if it beats Penrith on Saturday night.

“All of this stuff is great but you can’t get away from the fact that winning is good for business,” Sarantinos said.

“Winning makes a massive difference.

“The footy team has been consistently good for the last two or three years which allows you to do certain things off the field which you wouldn’t if you weren’t winning.

“For us, the recovery is done. That is gone now. I am kind of sick of talking about the recovery and the rebuild because we are so far past that.”

NEVER A THREAT

Phil Gould insists he never really worried about GWS. Once Penrith got its house in order, it would be impervious to outside forces, even ones as affluent and motivated as the AFL.

For a long time, Gould held out hope that the ARL Commission would play a role in Penrith’s reinvigoration.

He walked away frustrated.

The Panthers went out largely on their own, their regeneration in the face of the AFL threat perhaps best symbolised by Stephen Crichton.

Crichton was a target for GWS. He chose rugby league and is now an elite player, knocking on the door of higher honours,

“I don’t worry about the AFL at all, to be honest,” Gould said.

“In Sydney, the Swans were here for 30 years before I stopped and asked whether they won today. They have their own audience and I don’t have any problem with that.

“I have no problem with kids playing their sport of choice, as long as they are playing something. Our rugby league kids can’t play AFL and they can’t play our game.

“Our game has spent so much time worrying about people who don’t watch our game at the expense of people who love it. We are constantly trying to please people who don’t give a rat’s arse about our game.”

Gould didn’t always see eye-to-eye with former NRL chief executive David Gallop but, in that regard, they were on the same page.

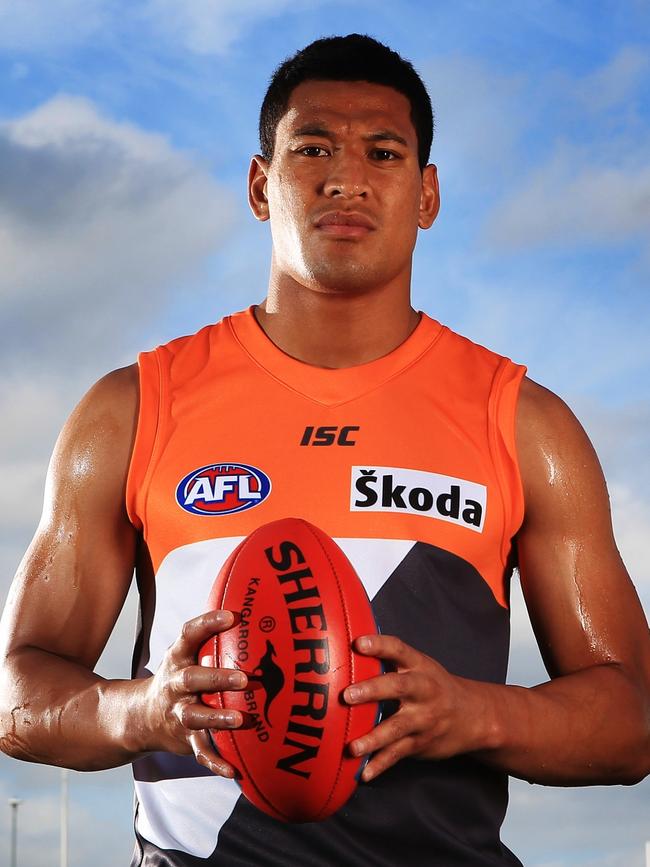

“While some of the loud voices in the game were predicting doom and gloom, we always knew that Israel (Folau) and Karmichael (Hunt) were a big risk and an expensive one,” Gallop said.

“In the end, it was a failure for the AFL. It showed that they were desperate to try anything to try to break the stranglehold that rugby league had over that area.”

Gould, now back in the southwest as general manager of football at Canterbury, added: “We don’t see much of them (the AFL) out in the west any more.

“They are probably still out there trying to promote themselves and do whatever but I don’t think it has impacted rugby league; or it hasn’t impacted rugby league because we got Penrith right.

“Penrith is now a force in the game and is competitive. Our thing was, if we get rugby league right, we wouldn’t have to worry about AFL.

“I never feared the AFL and if the rugby league did, they didn’t do anything about it. We fixed it by fixing Penrith and Parramatta did it by fixing Parramatta.”

THE FUTURE

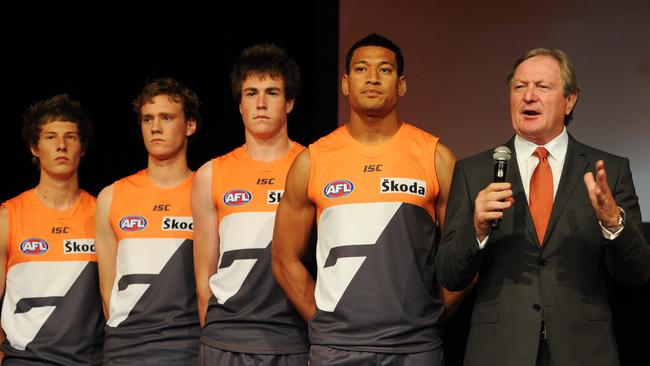

Ask Andrew Demetriou whether GWS has been a success and he insists the better time to make that call would be after the next decade.

The AFL has poured more than $200 million into the club and, while it has found a niche, it hasn’t really made a dent in rugby league heartland. For all the investment, its crowds were on the wane before Covid-19 intervened.

“I always said it was a 20- to 30-year exercise,” Demetriou, the former AFL chief, said.

“I would say it’s probably ahead of schedule. It has had very good success on the field for a club that has been in the competition for nigh on 10 years and it has produced some marvellous players.

“It is still a long, long haul. It is another 20 years. In the early years of GWS, when they were getting smashed, everyone thought this was a disaster.

“But it was pretty much on mark with where we thought it would be. I would say it’s on track to deliver what we thought it would.”

The NRL and its clubs remain on guard and the coming off-season will be spent fortifying its heartland. It will do so from a position of strength.

By the end of this season, more than 18 million eyeballs will have tuned in on television to watch the clubs in western Sydney.

“You’re never complacent, you never take anything for granted,” NRL chief executive Andrew Abdo said.

“What we need is a co-ordinated approach. We need a way to bring it all together and providing the best possible experience for all ages and all genders.

“The world is moving and changing. We need to change with it.”

That also means staying on your toes when it comes to the AFL. It isn’t going anywhere.

“All my rugby league mates in western Sydney said, ‘geez, you have put a rocket under us, haven’t you’,” AFL legend and inaugural GWS coach Kevin Sheedy said.

“I said, ‘well, let’s get everyone sorted and see how good you can be too because, at the moment, you are just rolling along’.

“All of a sudden they have V’landys. Would V’landys have been there if the Giants had not been there? Probably not.”

PART ONE: INSIDE STORY OF AFL INVASION

Penrith and Parramatta will meet in a western Sydney blockbuster in the unfamiliar surrounds of Queensland on Saturday night. A decade ago, these mortal enemies were locked in a turf war as rugby league’s heartland came under assault from the AFL and GWS.

In the first of a two-part series on how the west was won, we talk to the key players from a decade ago and go inside the war that had rugby league and its clubs warning that the battle for western Sydney was life or death.

Watch every 2021 NRL Telstra Finals Series match before Grand Final. Live & Ad-Break Free on Kayo. New to Kayo? Try 14-days free >

Don’t mention the war

Phil Gould almost lets out a sigh as he casts his mind back a decade and paints an emotive picture of rugby league’s plight in western Sydney.

“I was never worried too much about the AFL if rugby league got it right, which rugby league wasn’t doing,” Gould says.

“I said if GWS wins a comp in five years time and Penrith and the Eels are running last and second last, that won’t be a good look.

“I said where it is situated at the moment, if you leave Panthers in its current form to defend the west, maybe not in my lifetime but in my grandchildren’s lifetime, we will see an area where AFL dominates this part of the world.”

As Penrith prepare to meet Parramatta in Queensland on Saturday night, the sense is that rugby league has fortified its strength in western Sydney and ring-fenced the region from the AFL.

Had the game not been forced north due to Covid-19, there is every chance 70,000 people or more would have packed into Stadium Australia to watch the sudden-death final between two of the game’s powerhouses.

Yet go back a decade or so and western Sydney was a war zone as the AFL moved in and sought to capitalise on the sorry state of the two biggest clubs in the region – the Eels and Panthers.

Gould walked into a Penrith club that was on its knees. He was meant to be a coaching director but ended up being the general manger of football and, by extension, the face of rugby league in the west.

The Eels weren’t much better, struggling on the field and a political basket-case off it. The AFL was circling with money to burn and a deep desire to spend it as a means to ensure the success of the GWS Giants.

Former AFL boss Andrew Demetriou insists he wasn’t looking for a fight but it sure came looking for him. Demetriou was the man who bankrolled the AFL’s incursion into western Sydney a decade ago.

The man responsible for signing the blank cheques that lured Israel Folau across the sporting divide and saw the AFL launch a public relations blitz on rugby league heartland, putting up posts on lush green fields and threatening to take over hallowed ground at Birchgrove Oval.

For many in rugby league, it was a declaration of war. A life or death struggle for the code that prompted the NRL and its clubs to take a good hard look at themselves and re-evaluate the way they went about their business.

The message from NRL head office was don’t engage. Don’t give the AFL and GWS oxygen. Yet, rugby league couldn’t help itself as temperatures began to rise in the west. They were drawn in and the AFL relished the attention.

“You have to remember that we were in a situation that … in the greater western Sydney, AFL wasn’t slipping off anyone’s tongue,” Demetriou said.

“It wasn’t even slipping off the front of the tongue lobe to be honest. We weren’t known, the code wasn’t known.

“We had to try to make as much noise as we could to get noticed to be honest. In all parts of Australia you knew something about AFL, except in western Sydney.

“I remember one article that said it was going to be my Vietnam.”

The man responsible for that incendiary story was Geoff Carr, the former chief executive of the NSW Rugby League. It was Carr who suggested the AFL’s incursion into western Sydney would end the same way the Vietnam War did for America, a comment he stands by to this day.

“It hasn’t changed,” he says.

“The war is still on and they haven’t won it. They signed Israel Folau but they were all PR stunts. The goalposts was a PR stunt, the playing numbers was a PR stunt.

“I can remember they wanted to take over Birchgrove Oval. They went to the council and listed all the playing numbers, but at the end they had no club.

“It was all guns blazing. (Andrew) Demetriou, Kevin Sheedy – they just talked it up. We fell into them a bit. But I got sick of all the people saying how many goalposts there were.”

The goalposts

When it comes to the fight for western Sydney, you can’t avoid the goalposts. When the ARL Commission was formed in 2012, GWS was about to kick off its first season in the AFL.

The AFL had devoted years to wooing councils and government. They spent money hand over fist to have goalposts erected on grounds that were once the domain of rugby league.

It was a concerted and targeted campaign to claim the kids, every cold and calculating move run by strategists operating out of AFL head office.

“I remember everyone was obsessed with taking about the goalposts they saw springing up everywhere,” Carr said.

“They had this presence that wasn’t a presence. They had no playing numbers and no competition numbers.

“They were developing this huge myth about how they had taken over western Sydney. My view at the time – and it still is – is that was all smoke and mirrors.”

Still, one of the first things former ARL Commission chair John Grant did when he came into office at the start of 2012 was meet with Gould and representatives of the four western Sydney clubs.

The message was loud and clear – we need help to keep the AFL at bay.

“Gus (Gould) painted it as a very serious issue,” Grant said.

“Parramatta had their drama. Penrith had their own dramas with their own leadership. While they were rebuilding they lost traction and focus as well.

“We had the AFL investing another team in Sydney, which was a big deal. We had people appointed to the board of the western Sydney AFL side who were top shelf people in the business community in Sydney.

“They were investing in schools. They paid to put goalposts in. We were in a very poor position from the point of view of standing tall.

“The AFL made a big play.”

The AFL were cashed up thanks to a mega broadcasting deal that left rugby league in the shade. They talked a big game and had the money to back it up.

They also had a man who was happy to sell the cause. Kevin Sheedy was an iconic figure in the AFL and he was appointed GWS coach in late 2009, a full two years before the side would enter the AFL.

Sheedy made it his mission to press as much flesh as possible.

“I was an alien,” Sheedy said.

“We put an AFL team in the middle of four NRL clubs and stole a player called Israel Folau. We made about $12 million worth of publicity.

“I have it all written down, I have every photo. I used to go back after work and take photos of the stadium, where we started at Rooty Hill RSL.

“It is a classic (story).”

No meeting was too small for Sheedy. No-one worked the corridors of politics and local sporting clubs better.

“It was a PR war and I think to be fair, the media loved it,” said former Canterbury chief executive Andrew Hill, who was involved with GWS before returning to rugby league.

“It was great headlines. I think where Gus (Gould) was right was that rugby league was being complacent. Penrith weren’t as dominant. Parra hadn’t had success.

“As soon as they got Kevin Sheedy involved, it was headline after headline. Without Kevin Sheedy and Israel Folau, GWS wouldn’t be there they are now.

“If you looked at the media reports and media monitors, the in-kind value that club got from those two, no-one else would have got that.

“I guess it is a good example of the money that was at the AFL. League people would sit back and go what a waste of money, he (Folau) was hopeless.

“AFL people said we got it, we spent it and boy, didn’t we get some publicity out of it.”

The heartland strategy

With the game under siege, the ARL Commission responded by hiring a consultancy firm to put together a strategy for western Sydney. Christopher Brown was a long-suffering Parramatta fan when the NRL knocked on his door.

The commission wanted a broad brush view of western Sydney and a plan for making sure it remained a rugby league stronghold. From that meeting, the ‘heartland project’ was born.

Brown consulted far and wide as he sought the answers to rugby league’s vexing problems.

He spoke to politicians including now-opposition leader Anthony Albanese, a long-time South Sydney supporter, and former treasurer Joe Hockey.

He spoke to business leaders and powerful sports and media identities such as AOC president John Coates and 2GB star Ray Hadley. He was charged with finding out how the people with the power felt about rugby league in the west.

It wasn’t pretty. The secret report, which has been obtained by News Corp, is littered with anonymous quotes that paint a picture of a code that was out of touch with its constituents and badly trailing the AFL in corporate Australia.

“The NRL is crippled by its insular approach. Where is the new talent from outside its gene pool that the AFL has,” one said. Another added: “There is a lack of professionalism in the NRL.”

On and on it went.

“We are here spending millions trying to get consumers in western Sydney to look at our products but league just ignores its own powerful brand there,” another said.

The quotes also provided a snapshot into the way the AFL greased the government wheels and how naive rugby league was in that department.

“AFL was among the first to win the Premier after the election win,” one quote read. “They didn’t ask anything. Just wanted to say hello. NRL didn’t even invite the boss to Origin I.”

It was damning and it showed why rugby league was right to be concerned. The AFL was heaping pressure on a fractured code.

Parramatta and Penrith were in disarray. Country Rugby League and NSW Rugby League were at odds. The left hand didn’t know what the right hand was doing.

“The heartland strategy – it alerted them to the western Sydney issue and that they had a problem coming,” Brown said.

“Rugby league took western Sydney for granted for so long, never invested in it, it was a sport run by the eastern suburbs for the western suburbs.

“I remember growing up as a kid and things didn’t happen in western Sydney unless the publican and the rugby league guy approved it.

“They had this power that has dissipated. Have they done enough about the problem? Everyone has done a little bit of something.

“It is just almost structurally unable to be done. The warlords say this is our region, our club. The aggression towards head office – you are a bloated head office. There is a reason they are bloated – you have to do something.

“They have to get the will to impose themselves.”

Gould pleaded with the commission to take the west, and Penrith in particular, seriously. His plea he says fell on deaf ears, leaving the Panthers to dig their own way out of their hole.

“(The ARL Commission’s) first ever board meeting was at Panthers,” Gould said.

“We needed to talk to them about the position the Penrith club was in – both financially and from a development standpoint.

“To summarise it all, I said if you are relying on Penrith to protect the western areas of sport against the AFL, then Penrith can’t compete.

“We could have easily been out of business in 2011 and the league would have had no idea. John Grant promised he would help. We didn’t see him for five years.”

The fightback

Grant to his credit concedes the commission failed to bring the heartland strategy into effect.

They did, however, secure more money for the code through broadcasting rights and that gave them the ability to strike back.

The key though was the clubs. Parramatta and Penrith needed to get their houses in order. The Eels and Panthers are powerhouses now but a decade ago they were anything but.

They held the west in their hands.

Tomorrow: How Parramatta and Penrith got their act together and fended off the AFL

More Coverage

Originally published as AFL v NRL: Helicopter flight that shocked Peter V’landys